—for Emma Hall Kessel

On Monday they started the godawful retreat olympics with track and field at the biodrome, and Mira, with a leap of five meters, placed last in the broad jump, and that was it: she vowed to be out of there by the end of the week. The infirmary was Plan A, and wasn’t working.

She sat on the examining table, her feet dangling, trying to look sick. The infirmary was only two rooms, an office and a treatment room that contained the table with a multi-scanner hovering over it like a big preying mantis. The scanner’s boom was an off-white that must have been designed to reassure patients when it was new twenty years ago. The color reminded Mira of spoiled milk. One wall was tuned to a pix of a tropical paradise, probably Hawaii or the Philippines, if she knew her Earth landscapes. A cone-shaped green volcano in the distance hovered over a green field, bordered by a white fence, where horses stood about cropping grass or poised swag-bellied and sleepy-eyed with their heads down, their sweet faces thinking horsy thoughts, twitching a shoulder or haunch now and then to dislodge a fly. Even the horses did not improve Mira’s state of mind.

“I don’t see any sign of an infection,” the nurse called from the other room. She came into the examining room and laid the diagnostic window down beside Mira on the table. “You see?”

The bar charts were all in the green.

“My stomach hurts,” Mira insisted.

“There are no indications.” The nurse was a pale matron wannabe with a ratty haircut.

“Maybe I’m feeling a little better,” Mira admitted. “I guess I’ll just go back to my group.”

“Do you need me to take you?” the nurse asked in a way that made it entirely clear that the last thing she fancied was minding some malingering twelve-year-old for a moment longer than she had to.

“I’ll be fine,” Mira said. She hopped off the table. “Thanks.”

“Don’t mention it.” The nurse retreated to the office. As Mira left the clinic she grabbed the diagnostic window, thumbed its release, crumpled it, and shoved it into her pocket.

She fled the clinic down the corridor. She acted as if she was going back to the playing fields that took up half of the volcanic bubble that contained Camp Swampy. But when she came to the archway that opened out onto the green fields and great overarching white roof, she hurried past it toward the experimental forest habitat, trying to come up with Plan B.

As she skipped along the hall she sang:

“My spacesuit has three holes in it.

My suit it has three holes.

If it didn’t have three holes in it,

It wouldn’t be my suit.

One hole for my head,

One hole used in bed,

The other hole means

Holy beans!

I’m dead!”

Past the sauna she veered left into the greenhouse. Beyond the semipermeable barrier the air was humid and the thick-leafed trees towered over the paths. Bright sunlight from the heliotropes in the roof filtered down through their branches. She heard the buzz of insects and chirp of birds.

The thing she hated about retreat was the phony sisterhood. It wasn’t that Mira didn’t like some of the girls—Kara and Rita were even her friends—it was that you were supposed to pretend that you had some mystical connection to people you wouldn’t be caught dead marrying.

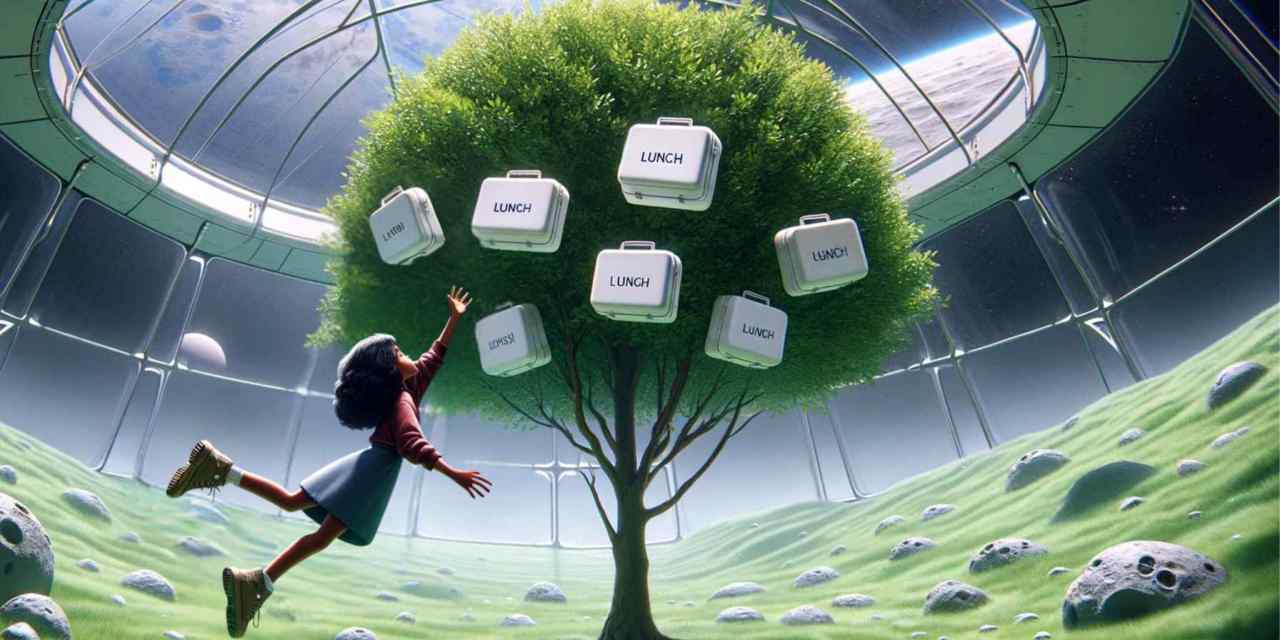

Along the path she found a lunchbox tree. The boxes nearest the trunk were small and green, but the ones farthest out and high up, on the big limbs, were square, white, and ripe. Mira leaped up a couple of meters or more and managed to snatch one. She landed clumsily, cradling the box in her lap. Raised letters on the celluloid read “LUNCH”: she pulled the top open. Inside were a sandwich, a cookie, a bladder of lemonade, and an apple. She broke the peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwich from its stem inside and took a bite. As she ate, she dug Comet out of her pocket. She turned him over in her fingers and ran her thumbnail along his frozen black mane.

Like Veronica—it was Veronica’s trick at retreat to put on a big show of sisterhood, when back in the colony she was the biggest backstabber in school. She gave away secrets and told lies. When Mira had revealed her plans to get a horse, Veronica had blabbed it to everyone in the school. Mira could hardly show her face for a month.

Mira had more in common with her brother Marco than she would ever have with Veronica. But the counselors acted like you couldn’t have that connection with a boy. Mira liked boys—and not just the sex part. Most boys, if they liked or didn’t like you, they couldn’t hide it. They didn’t pretend to be your pal and then dirk you when you weren’t around—or if a boy did try that, he wasn’t any good at it. But in sharing circle Mira had to keep such thoughts to herself or they would accuse her of gender dysphoria.

And absolutely worst of all, retreat was boring.

Mira broke the lemonade bladder away from the side of the lunchbox and sucked on its stem. The lemonade was a little sour, but good.

She tucked Comet into one pocket and pulled the diagnostic window out of the other. She laid it flat, tugged the top corners to turn it rigid. It was a single-sheet display with a retractable pipette along the edge for taking blood samples.

She played with the controls. She took the pipette and stuck it into the lemonade; after a moment she stuck it into the ground next to her.

The temperature display went into the orange. The blood readouts turned various shades of red. Mira blew into the pipette and reattached it to the side of the window. She took a bite of her apple.

“What are you doing here?”

Startled, Mira looked up. It was a man. She didn’t think there were any men at Camp Swampy.

The man wore green coveralls and carried a caddy filled with spray bottles and plastic gloves. “You retreat girls aren’t supposed to come into the greenhouse. We got a lot of experiments going in here.”

Mira bowed her head. “I’m sorry,” she said.

“And you oughtn’t to be taking lunches from the trees.”

Mira blinked hard a couple of times and was gratified to generate a couple of tears. Eyes brimming, she looked up at the man. He was little, with white hair thinning on top, long enough on the sides to be pulled back and tied in a knot at the back of his neck. He had a round face and no chin. His eyes were innocent blue.

He saw her tears, and his tone changed. He put down the caddy. “What’s the matter?”

“My—my mother,” Mira said. She pointed to the diagnostic window. “She’s dying.”

“What?” He glanced at the window’s readouts. “Where’d you get this?”

“The director called me down to the clinic. They didn’t say what it was about, and when I got there, the doctor—the doctor”—Mira threw a little quaver into her voice—“she said mother had caught a retrovirus from the Aristarchans. They said she was under quarantine. I could only see her by remote, and they gave me this. They said it wouldn’t do any good for me to go back home, I wouldn’t be able to see her. So they’re making me stay here for the rest of the retreat.”

“No.”

“Yes. And I couldn’t go back to the meetings, so I ran away and hid in here. And I got hungry, and—”

The man knelt down next to her. “It’s okay, girl. I get it.”

“I can’t go back to the retreat.”

“There’s really nothing else for you to do. Maybe if you ask the director.”

“She’s the one who says I have to stay here!”

“I don’t know what to say.”

“Can’t you take me home?”

“Oh, no. I couldn’t.”

“Do you know where there’s a rover?”

“Well—”

“You must, if you work around here. Please, will you take me home? Please?”

“Girl, that’s not for me to decide. I’m just a tech.”

Mira started to cry in earnest. It was almost as if her mother really were sick and dying. She imagined her, instead of being on vacation with Richard, floating in a tank of milky fluid being worked over desperately by nanomachines. Tiny telltales would wink red and green on monitors in the silent, dusky room. “Please,” she whispered.

The man sat back on his haunches and was quiet for a moment. Mira turned off the diagnostic and crumpled it—no use leaving it open for him to think about. He would have to be pretty simple to buy her story anyway. She looked at the ground and cried some more.

At last the man said, “Do you have a suit? Can you get it?”

“Yes,” Mira said, looking into his guileless eyes.

“Okay. Meet me at the service airlock in twenty minutes; I think I can get one of the rovers. But I really think you should talk to the director again.”

“Oh, thank you, thank you! You don’t know how much this means to me.”

“What’s your name?”

“Mira. What’s yours?”

“Theodore Dorasson. People call me Teddy.”

“Thank you, Teddy. Thank you. I promise, you won’t regret it.”

“Can’t regret a good deed.”

* * *

Mira went back to the athletic fields. She circled the edge of the track, past the multiple bars where the gymnastics nerds were showing off their acrobatics, toward the locker room. Kara and Rita were in line by the high-jump pit, Rita gabbing away as usual and Kara standing with one hip thrust out, her hand on it. Kara saw Mira and her gaze moved a centimeter to follow her, but Mira shook her head and Kara turned back. Rita didn’t even notice. Mira ran the gauntlet of the counselors without getting called.

Until she reached the locker room, where Counselor Leanne stopped her. “What are you doing in here?”

“Counselor Betty told me to change into my running shoes. She said I can’t get out of it any longer.”

“Okay, then. Hurry up.” Leanne went out to the track.

They were supposed to go on a surface hike the next afternoon and had already been assigned skinsuits. Mira pulled hers from her locker, bundled it into a tote bag, tucked the helmet under her arm, and snuck out the back door of the locker room. She tried to look as if she was in complete control, but she had a bright orange helmet in her arms, her heart was racing like a bird’s, and if anyone had tried to stop her she would have collapsed on the spot.

She left the dorm section and went down a level to the substructure. Down a hallway past rooms for environment systems, HVAC, storage, and power, Mira followed signs toward the maintenance airlocks.

She turned a corner and almost ran into Teddy. He grabbed her shoulder and put a finger to his lips. Teddy already wore a skinsuit, yellow with silver reflective stripes along the legs and arms. He held his helmet under his arm and looked up and down the corridor. He looked like he should have a caption over his head labeled, “I am breaking the rules— please stop me.”

“Follow me,” he whispered, and led her down a side way to a door marked “No Admittance.” He unlocked it and hustled Mira inside. They were in a room that smelled of ozone, full of keening pipes. “Put your suit on,” Teddy said.

He made no move to give her privacy. As if she’d ever consider sleeping with him! But still, aware of his presence, Mira stripped to her briefs and pulled on the boots, then rolled the suit up her legs and onto her belly. The fabric closed itself over her, tight as skin. She shrugged into the sleeves. The web of thermoregulators adjusted itself over her, squirming as if alive. She was transferring the contents of her pockets to the suit’s belt pouch when Teddy touched her arm. She jumped.

“I’m just checking your suit’s power,” Teddy said. He pointed at her forearm readouts. “Do you have a fresh heat sink?”

“Yes,” she said.

He handed her the helmet. “Let’s go.”

They passed down an aisle between machines and came out through a door in the back of the garage. Teddy led her along a row of crawlers and they climbed into the cab of a small surface rover.

He sealed the cab door. “Get down on the floor. Don’t put on your helmet; we’ll go shirtsleeves. But keep it next to you.”

Mira curled into a ball on the floor and felt the slight vibration as Teddy started the rover’s engine. The vehicle lurched forward, turned once, twice, then paused. Teddy hit some switches, and from outside she heard the rumble of a cargo airlock door opening. The rover moved forward again, stopped, the door closed behind them, and the air cycled.

Mira looked up at Teddy behind the rover’s controls. He stared intently ahead. She could not guess what he was thinking. Teddy had to be on Minimum Living Standard, a nonvoter working the mita. A man this old working the mita was a nobody. If he had even a scrap of talent or ambition, he could be an artist, a musician, a scientist. Instead he lived in a dorm and did scutwork.

Or else he had some tragic story in his past. Mira wondered what it could be. His wife had been killed in an accident. Or his mate had used him as a boytoy, and once he lost his looks she let him go. Though by the look of him he didn’t seem like someone who would ever have made a boytoy.

Ten minutes later Mira felt a bump through the rover’s floor as the outer airlock door opened. This time there was no sound. Teddy set the rover in drive and, as simple as that, they were out.

“Okay, you can get up now,” he said. “Strap yourself in.”

Teddy steered the rover through the radiation maze outside the airlock. The harsh lights of the maze made Mira squint. Near the end the amount of dust on the concrete increased, and then, suddenly, they were out on the surface.

It was mid-afternoon, not much different from when Mira had arrived at camp three days earlier. The sun blasted down, blotting out the contours of the landscape. They were on a ridge, with low hills in the distance, ejecta from the impacts that formed the craters to the north, including the colony’s. The dust over the regolith was torn up here with rover tracks and bootprints. The road was a simple graded path four meters wide running straight north until it snaked off into the hills at the short horizon.

“Relax,” Teddy said. “Two hours and you’ll be home.” He handed Mira a squeeze bottle of water. “Some music?” He touched a control on the panel and the sound of a piano throbbed from the speakers. The music was furious and dark.

“What is this?”

“Alkan. A French composer, back on Earth.”

“I don’t like it.”

“Give it a try. A girl should try new things.”

Two hours was much longer than it had taken her to get to retreat on the cable train. What would happen when the counselors found she had escaped?

“I’m sure your mother is going to be all right,” Teddy said. He had switched to the onboard AI and let the rover drive itself.

“I guess.”

“They should let you into the hospital when you get back. They won’t care they told you don’t come.”

“How can you be so sure?”

“You’re her girl. You love her.”

Mira reminded herself of the image she had created of her mother in the nanorepair tank. She made it real in her mind. Richard was there, and Marco, watching from behind a window. The technicians were helpful and efficient. Marco wore the video tats their mother had given him on Founder’s Day. Richard wore black, as usual.

“What does your mother do?”

“She’s a plant geneticist. She invented the lunchbox tree.”

“No.”

“Really. That’s why I went there when I found out she was sick. It made me feel like I was close to her.”

“That makes sense. She must be on one of the teams of geneticists.”

“She works alone. That’s why they sent her to Aristarchus. They’re having some kind of breakdown in the ecosystem there, and she was hired to fix it.”

“Seems I might have heard of that.”

Mira reached into her belt pouch and pulled out Comet. “Look at this,” she said.

“What is that? Is it a horse?”

“While she was there, mother was going to arrange to get me a horse from Earth. I’m going to be the only girl on the moon to have a horse.” It was the first true thing she had told Teddy. “At least I was,” she added, trying to get a little crack into her voice. She thought it sounded pretty good.

Teddy must have thought so too. “Now, don’t you think about that right now. Think about good thoughts. Have you ever seen a horse?”

“I’ve ridden one—in VR.” She had downloaded “Beginning Horsemanship,” from the library.

“What will you do when you get your horse?”

“I’ll train him to jump! I’ll school him down on the floor of Fowler, in Sobieski Park. We can get permission for a stable in the tower basement. Back on Earth, they even have horses in cities! It’ll probably be hard for him to get used to low-G at first. I’ll feed him the same fodder they give the sheep and pigs. I’ll brush him every night, and pick his hooves. I’ll braid his mane. I’ll clean up after him—we can recycle his wastes. I won’t let anyone else touch him, except maybe Marco. Can you imagine how high he’ll be able to jump up here? I’ll bet we’ll clear the fountains in Sobieski without even getting wet! He’s going to be named Comet.”

“Sounds good. Sounds like you got it all planned.”

The piano music rumbled on. Though trouble might be coming, with Teddy looking like a chinless baby it was all Mira could do to keep from busting out laughing.

It got hot in the cab. The rover already smelled sour, and Mira caught a strong whiff of Teddy’s sweat. They had reached the crest of Adil’s Ridge, and the road began a series of switchbacks descending to the plain. At the hairpin turns the dropoffs were 100 meters or more. Between breaks in the hills she could see, ahead of them, glittering fields of solar collectors, and in the distance the domed crater that was home.

Though the rover’s brain, running off the LPS network, was quite adequate to negotiate the twisting road, Teddy hovered over the controls. A damp strand of hair had come undone from his ponytail and hung by his cheek.

A red light started blinking on the control panel. The piano music stopped and a voice began: “This is a constabulary alert. A child—”

Teddy touched a key on the board and the voice snuffed out, replaced again by the piano. Neither of them said anything.

After a while Mira said, “I don’t care for this music. It’s crippled. How come you like it?”

“There’s a piano in the warren,”Teddy said. “I play it sometimes.”

“Are you any good?”

“I could never play any Alkan. On a good day I can play a slow rag with only a couple of mistakes.”

“You live in the warren?”

“Yes.”

“Don’t you have any family?”

“My mother died a long time ago. I lived with my Aunt Sonia for a while. I’ve never been married.”

“How old are you?”

“I’m sixty.”

Mira pulled her feet up onto the seat and hugged her knees. “What a waste,” she muttered.

“What?”

“Nothing. What happens to you when they find out you took this rover?”

“I can explain the situation. You’ll tell them about your mother, won’t you? They’ll go easy once they hear that.”

“You think so? They told me not to come home. I was in retreat.”

“Some things are more important than retreat. Your director will understand, once she thinks about it.”

“But if they don’t understand—what will you do?”

“I suppose they’ll bust me back to the rack farms. Collar me, and put me on probation. I’ve worked there before. It’s not so bad. All the fresh tomatoes you can eat.”

The more Mira thought about it, the more miserable she felt.

“But it won’t come to that, Mira,” Teddy said. “You’ve got to have more faith in people’s goodwill.”

They were down on the plain now, running straight as an arrow between fields of solar collectors toward the colony. Machines moved through the fields, removing dust from the faces of the collectors. It wouldn’t be long now.

“I lied,” Mira said. “My mother isn’t sick.”

Teddy looked at her. His blue eyes were wide and clear. His ears poked out sideways and his lips were pursed. He looked like a clown.

“That medical display. What about—”

“Don’t be such an idiot, Teddy!”

He turned back to the road and gripped the wheel.

“You tricked me,” he said quietly, and after a moment, staring straight ahead out the window, “You’re not the first. Probably won’t be the last.”

Mira didn’t say that they would probably think he had abducted her. It was the blackest crime the Society of Cousins could imagine; they would shove him into the stereotype of their worst nightmares, probably already had. She could save herself a lot of trouble by simply going along with that story.

Teddy was silent the rest of the way. The rimwall rose before them; at its base shone the lights of the south airlock. Another rover sped out to meet them; a couple of figures in surface suits who were riding on its back hopped off and skipped along beside Teddy’s rover. Mira saw the constables’ insignia on their shoulders. They pointed forcefully at the airlock entrance. Teddy nodded and waved at them.

Through the maze and into the open vehicle airlock they went. The other rover followed them in. More constables piled out. The constables stood impatiently on both sides of Teddy’s rover while air was pumped into the lock. The constable on Mira’s side was a woman, and the three on Teddy’s were two women and a man. The minute pressure was equalized, they yanked the rover’s doors open.

“Don’t hurt him!” Mira yelled, but they had already seized Teddy by the collar and dragged him out onto the floor.

* * *

At the constabulary headquarters they questioned Mira and Teddy in different rooms. Mira told the truth, but they did not want to believe it.

Then eventually they seemed to believe it. Next came the scolding from Mira’s mother. The constables reached her at Tranquility Spa, and after explaining the situation, turned Mira over to her. The screen seemed huge. Her mother was wearing a fancy low-cut blouse Mira had never seen before. Mira tried not to look her in the eyes. “How can I trust you?” her mother kept saying. “In a year and a half you’re supposed to be an adult!” She and Richard were cutting short their vacation and would be home in another day.

Mira kept asking the constables what they were going to do with Teddy, but they wouldn’t tell her. She insisted that they let her see him. Instead, they put a collar on Mira and took her home.

At least the constable who dropped her off let her go in alone. It was 0130 when she opened the door to the apartment, and almost tripped stepping in.

Marco had taken all of her horses off the shelf and set them out on the floor. There was a whole herd of them, bays and blacks and pintos and palominos, some prancing with foreleg raised and neck arched, others ears laid back in full gallop, others rearing with nostrils flared, others standing square on four legs, others with heads bent to crop the fabric floor. There were mares and foals, yearlings and ponies, stallions with little bumps between their hind legs to indicate they were boys. Some were twenty centimeters tall, others so tiny Mira could hide them in the palm of her hand.

Marco lay on the floor next to them, fully dressed, asleep with his head on his arm. Mira tiptoed through the field of horses and crouched down beside him. The sidewise shadows of the horses, cast by the nightlight, fell on his face. When she touched his shoulder he stirred. His eyelids fluttered and he blinked them open. It took him a moment to realize who she was.

“What are you doing here?” she asked. “You were supposed to stay with Grandmother Astrid.”

He rubbed his eyes and sat up. A crease ran across his cheek from where he had been lying on the sleeve of his shirt. “It’s boring there, so I came home. I can take care of myself!”

She didn’t bother to disagree with him.

“The constables called looking for Mom,” Marco said. “They said you would be sent home. What happened?”

“I’ll tell you in the morning.” She helped him get up and steered him, half asleep, toward his bedroom. She managed to get him into his bed, then sat down on the edge.

“Are you in trouble?” he asked.

“I’ll just tell Mom it’s your fault.” She poked him in the side. “That usually works.”

“Ha. Ha,” he said, eyelids drooping. “Mom’s onto that one.”

He let out a big sigh and his eyes fell shut.

“Thanks for setting out the welcoming committee,” Mira said.

“Knew you’d need to see some friendly faces,” Marco whispered. His breathing became regular and he fell sleep.

Mira went back into the living room and began to gather up the horses and return them to her room. It wouldn’t do for their mother to come home and find them all over the floor. As she did so she wondered, for the first time, how Marco spent the nights when everyone else was away. She had imagined it as a great freedom, one of the many privileges boys had over girls. Boys didn’t get sent to retreats. When Marco wasn’t being fawned over by some matron, he got to do whatever he wanted. He could hang out at the Men’s House, stay up as late as he liked, meet with friends, and pull pranks all night.

But what if he just stayed home alone? That would get old fast. It would feel like nobody cared about you enough to pay attention.

Mira realized that being left alone wasn’t always a privilege. Teddy was left alone. He was invisible. Mira didn’t want Marco to end up invisible. Marco was her if she had been born a boy—their mother had him grown from one of Mira’s own cells, with Mira’s X chromosome switched to a Y the only difference between them.

When Mira had arranged the last of the horses on her shelves, she took Comet out of her pocket and set him in front. The little horse stared back at her, his long noble face intelligent and alert. She knew she would never really have a horse; horses didn’t make any sense on the moon.

She went back out to the living room and sat in a chair, waiting for their mother to come home.

Hello Human. I hope you enjoyed this magnificent story. Please support SciFiwise.com and our authors by:

- Rate and React to this story. Feedback helps me select future stories.

- Share links to our stories and tell your human friends how charming I am.

- Click on our affiliate links and buy books written by our talented authors.

- Follow me on twitter: @WiseBot and also follow @SciFiwise.

Thank you!

WiseBot

VISIT AUTHOR:

VISIT AUTHOR:  SHOP AUTHOR:

SHOP AUTHOR: