Aboard the Final Theophany I had assembled a small but efficient crew consisting of the meanest, deadliest, orneriest, smartest and most embittered set of intergalactic killers I could dredge up during ten years of cruising all the lanes of civilized space and quite a few of the more savage precincts. Out of sheer self-indulgence, I had given them all human names familiar to me so I wouldn’t have to be bothered with trying to recall or pronounce their original exotic monikers. After all, I was Captain and footing all the bills.

Maxwell Silverhammer stood three meters tall in his bare green scaled feet and carried, as if it were a toothpick, a giant mallet whose head was fashioned of purest quark matter from the heart of a neutron star. The portion of his face not taken up by black fangs was filled by one enormous bloodshot eye.

Jagello appeared at first to be merely a sessile nest of whiplike, besuckered tentacles surrounding a sharp parrot beak of a mouth. But then he would reveal enormous snapping chelae that could propel him at lightning speed and which were capable of snipping a man in half.

Drumgoole manifested as a grey-complexioned wispy wraith with a mummy’s face, all parchment skin and kite-stick bones, flimsy as a clothes rack. But when he enfolded his victim and began irresistibly tightening, all impressions of fragility vanished.

Corinthia, barely one meter tall, hailed from a heavy planet and resembled a troll or gnome from Terran legend, down to a complexion full of warts and scars, and a nose like a small cucumber. I had seen her stop a fusillade of shredder flechettes with her formidable chest, leaving her laminate armor like Swiss cheese but her bruised skin intact.

Myself, I go by the name of Moortgat, and although technically human—whatever that means these days—my kind is divergent from the baseline. I’m the result of inbreeding for survival on a deathworld where every element of the ecosphere was lethal to the human species. My skin exudes toxins, my eyelids are impenetrable, a braid of three of my hairs can serve as a garrote, and my farts are explosive when voluntarily primed. Not a pinup boy.

Seeing this ugly, fantastical assemblage of beings—and I included myself of course—some ancient, pre-spacefaring Terran might have thought that we represented a good assortment of aliens from around the multifarious galaxy, a panorama of the myriad heterogenous miracles produced by the ingenious Darwinian chemistry and physics of our different worlds.

But of course, nowadays everyone knew better.

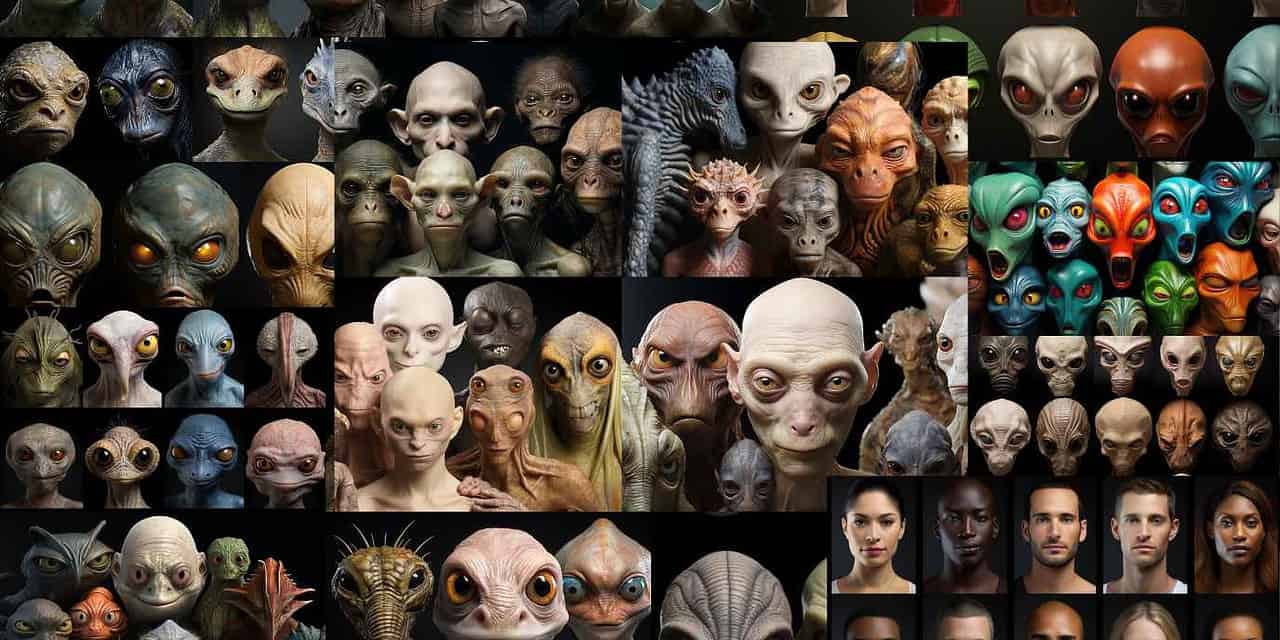

“Aliens” did not exist. Nowhere in the galaxy could be found a sophont with an utterly exclusive genome.

Every sentient creature in the universe, no matter how oddball their physiognamy, was genetically related.

We were all one species, sharing up to ninety-nine percent of our genes, all of which used the universal DNA substrate. Same amino acids, same method of translation into proteins, all the same cellular processes right down the line.

Had any of us four males onboard the Final Theophany wished to do so, and had it been physically possible in any particular mating to connect genitals, we could have inseminated Corinthia and produced a viable fetus. (Believe me, this was not a fantasy that any of us harbored.) Even without a carnal connection, such a thing could have been easily done artificially with nothing more elaborate than a syringe.

Just like Terran canines, which ranged from half a kilo in weight to well over one hundred kilos, and exhibited a huge range of appearances, the intelligent population of the galaxy hid cellular uniformity beneath their varying facades. We were a universe of mutts. Admittedly, the analogy was inexact, the situation more bizarre than with dogs, given the anatomical gap between, say, someone like Jagello and the rest of us bipeds. But even if scientists still had their questions about certain aspects of how we remained interfertile despite such large variations (they often rang in embryological morphic resonance), the basic fact was scientifically incontrovertible.

Every single sophont across a hundred billion star systems was related. Or so we surmised, based on an incomplete expansion across about one-third of that realm.

Of course, such a finding immediately raised the question of how such consanguineity came to be. Ours was the first interstellar age. No previous FTL empires had ever existed. The archaeological records had been plumbed on a half million inhabited worlds without producing one shred of evidence for any widespread civilization of forerunners. So the scenario where an empire of homegenous beings decayed and, over a few million years, sent its isolated populations down a variety of evolutionary paths proved untenable.

In the end, the best theoreticians in the whole galaxy were left with only one reasonable hypothesis.

All the races of the universe had been seeded separately by some individual or small band of individuals, leaving no archaeological traces and employing as root stock the same malleable germplasm.

In other words, there was a Creator, and He or She or It had populated the galaxy with His or Her or Its designs. (Let’s call that bastard God Him from now on, for convenience.)

In many individuals, this scientific revelation inspired awe, reverence and bliss.

In myself and my crew, the notion of a God who had promiscuously fecundated our galaxy with a plethora of intelligent races of all body plans had instead engendered hatred, disdain and rage.

You see, each of us—Maxwell, Jagello, Drumgoole, Corinithia and yours truly, Captain Moortgat—had belonged each to their own world’s One True Religion which maintained that the Creator had fashioned the dominant species of our “unique” world in His Own Likeness. It was a belief born of primitive planetary isolation, and maintained precariously in the early years after First Contact. But after a few centuries of discovery and correlation, the widespread broadcast about the reality of universal miscegenation had definitely killed it.

This irrefutable revelation—that all the galactic races issued from the hand of the same mad demiurge who had, in addition to crafting his “chosen” race, spawned equally privileged “monsters” left and right—had sparked suicides and apostasies galore.

But in us five it had bred only one overwhelming urge.

To find and assassinate the irresponsibly profligate God who had made us.

* * *

For a group of five sentients who hated each other’s guts, we got along pretty well. The fact that each one of us was a living affront to the bedrock theology of the others—an affront each of us longed to bloodily erase—was subsumed in our quest to find and kill God. Of course, my appropriately heavy poison hand of discipline, employed only when necessary, also helped to maintain a surface calm.

So once we were underway along the navigable labyrinth of the Dark Matter Web that threaded the visible cosmos and provided galactic civilization with its FTL links, I had no hesitation about calling my crew out from their private cabins and assembling them in the refectory of the Final Theophany for a discussion of our plans. I expected them to behave even in those close quarters—or else.

No chair was big enough for Maxwell, so he just towered by the table’s edge. Corinthia, on the other hand, had to perch atop several pillows on her seat to see over the rim. Resting on the floor, where he left a spreading trickle of scummy brine, Jagello simply extended an eye stalk up to the common level. Drumgoole seemed to float an inch or so off his seat, wafted back and forth by the room’s gentle ventilation.

“All right, you mooks,” I said, “listen up. Now that we are away from any chance of being overheard by busybodies wo might try to stop us, I can reveal our first destination. We are going to make a raid on the Syntelligence Institute on Souring Nine. Our goal is to kidnap one of their boffins, a human named Ilario Mewborn.”

Jagello’s voice sounded like a toucan crunching an entire stalk of bananas. “What for we take this man?”

“Because he’s discovered how to track God.”

If I had closed my eyes, I could have imagined Corinthia’s husky tones emanating from a sexy gal of my own planet, someone whose epidermal toxins would have blended with mine to make an aphrodisiac sweat paste. Of course, the gruesome reality of the dwarf was nowhere near as alluring.

“You signed us on with the promise that you already had a way to track the creator. What gives?”

“It’s true, I do have a stochastic projection of His path. But I just learned that Mewborn’s got something much better.”

Determined from the fossil record and biological markers, the evolutionary age of every sentient race so far discovered had been precisely calculated and arrayed in a database, then sorted. The oldest race proved to be the Thumraits, aquatics who resembled a cross between a squid, a seahorse and a clam. Their fossil record extended back five million years. The youngest race so far encountered were the Quisqueya, a bunch of plump pancake-shaped things that lived by clinging to the rock faces on their world, absorbing sunlight and licking fermenting moss. Their existence stretched back a mere three-quarters of a million years, and they had not even achieved their full sentience yet. But their sampled “human” genome was unmistakeable.

Now, playing connect-the-dots with the planets of the sentient races in order of their age produced a unidirectional path for the Creator’s malignant life-spawning journey, a path which could be extended out beyond the Quisqueya into the unknown lightyears with a certain degree of accuracy, assuming, as we had to, that the Creator was still active some three-quarters of a million years after his last recorded abomination. My plan had been simply to follow the projection, stopping at every likely world.

I explained all this to my crew.

Maxwell rumble-lisped a response. (Large fangs did not an orator make.) “And thish Mewborn, what ish hish invention?”

“He’s discovered that the Creator’s method of travel leaves a distinct signature in the Dark Matter Web. The signature is almost eternal, but fades with time. He’s plotted the traces against the archaeological record and it fits perfectly. We can use Mewborn’s gadget to home in on the Creator’s current whereabouts much faster and with more certainty than by following the stochastics. We’ll just ride His transportation gradient until we come upon His present location. Then—goodbye, God!”

Drumgoole’s hypnotic voice, one of his tools for taking prey, resembled a ghoulish whisper from another dimension.

“I will guarantee this human’s cooperation, have no fears.”

“Fine. Then we’re all in agreement. Souring Nine, here we come!”

The defenses of the obscure and isolated Syntelligence Institute were laughably rudimentary. Nothing but a few robotic security guards patrolling the outside perimeter. They were brought to a juddering stop with the broadcast of a simple Universal Halting State trojan. Confident that their lofty, pure researches held no allure for thieves or pirates, the Institute had never hardened up. A blow from Maxwell’s weighty hammer took the front door of the Institute clean off its hinges and sent it rocketing across the empty reception area.

Expecting a mob of workers and panicked screams, we got only emptiness and silence.

“Where the hell is everybody?” Corinthia demanded.

“Don’t know, don’t care,” I said. “We’re just after Mewborn’s tracking device. Let’s move before the cops show up!”

After dashing down corridors where several doors led to labs and storerooms but no offices, it finally dawned on me that the staff of the Syntelligence Institute consisted of Ilario Mewbon alone.

We found the boffin cowering under his desk in a centrally located room. Jagello extended a claw and pulled him roughly out.

Ilario Mewborn presented as a puny baseline human, and not a particularly impressive specimen at that. Sparse strands of mouse-colored hair failed to conceal his spotty scalp. He stood not much more than one-and-a-half times Corinthia’s height. His drably wrapped limbs approximated Drumgoole’s spidery structure. And for some reason he wore antique eyeglasses. (I learned later that he was allergic to contacts and scared of surgery or implants.)

Although not as loud or basso profundo as Maxwell, I had a respectable bellow. “Where’s the Creator tracker? Quick!”

Mewborn’s quavering voice sounded like a goat’s bleating. “Oh-over th-there….”

I walked to where he pointed. A large plastic drum was the only possible item. I pried off the top. Inside quivered a translucent gelatinous mass threaded with glowing, sparkling organelles.

“What the hell is this!”

“It—it’s the tracker. Honest, it truly is!”

Approaching sirens penetrated the building.

“Grab everything, Mewborn too, and let’s roll!”

The Final Theophany showed Souring Nine her tail faster than you could say, “God is dead.” We were in the unpursuable depths of the Dark Matter Web while the planetary cops were still unlimbering their guns.

In the refectory the five of us crowded with a menacing expectancy around a seated Mewborn. With sweat dotting his brow, the little scientist sipped delicately at a glass of restorative electrolytes and cyana-berry juice, his composure gradually returning. Finally he looked calm enough for questioning to be effective.

“Okay, pal, what’s with the tub of pudding?”

Mewborn’s voice exhibited a certain disdain at my ignorance and pride at his own accomplishments. “That, my loud and pockmarked thief, is urschleim, my own discovery and invention. It’s taken me decades, but I’ve done what everyone said was impossible. Employing every single genome of all the sentient races, I have reverse-engineered the mother plasm from which they all arose. In that barrel you behold the raw material employed by the Creator, the clay from which we were all initially fashioned.”

I went to the barrel and peered in with more respect and curiosity than before. “Can you use this stuff to make new races then?”

Mewborn grew crestfallen. “No, that supreme accomplishment is, as yet, denied to me. But I intend to learn how from the Creator Himself.”

“And this urschleim will lead you too him?”

“Indeed! It resonates superluminally to his presence, like an infinitely sensitive radar with only one target. I have learned how to interpret the patterns of the urschleim’s twinklings, which mirror the traces of the Creator’s passage through the Dark Matter Web.” Mewborn got up and moved to examine the sparkling gelatin. “And right now, our course is taking us away from the Creator! You need to reverse at once!”

Before mindlessly following Mewborn’s advice, I consulted the alternate stochastic analysis of the Creator’s projected trail and found it agreed. “Okay,” I said, “you call the course until we reach God. But I gotta warn you: you’re gonna have to question Him real quick, because He’s going down for a dirt nap as soon as we lay eyes on Him. Unless we decide on a little torture first.”

Mewborn used a forefinger to slide his glasses further up his nose. “I expect God might have something to say about His disposition as well.”

* * *

The five of us would-be Godkillers once more occupied the dining area. We had installed Mewborn and his vat of amalgamated jellyfish guts in his own cabin. The door remained unlocked: there was no place he could run, nothing onboard he could sabotage, no way he could communicate with any authorities.

I addressed my posse. “You dickheads can wipe those satisfied grins off your faces.” I was stretching the facial complacency accusation a bit here in Jagello’s case. “The easy part of this mission is over. Now starts the rough stuff. First off, we’re going into uncharted territory. No telling what kind of weird astrophysics we’ll run into. No one even knows if the Dark Matter Web remains navigable in the same way out here. Redmayne and Crispwell set out to chart it, and they never returned.”

Jagello rasped out a question. “What for maybe we worry about other sentients? What trouble they bring?”

“Well, figure it out for yourself. The youngest race in our neck of the woods is the Quisqueya, and they haven’t even conceived of the wheel yet. Every other Creator-endowed sophont we encounter is going to be even younger. Now, for sure, some races might have been created meaner and and more on the ball initially than those pancakes. And local conditions might have forced them to evolve faster. But I’m still betting none of them have attained spaceflight yet. And, unlikely as it seems, we might even find some non-Creator-determined independently intelligent species. Don’t hold your breath.”

A senseless comment to make to Drumgoole, who performed his internal gas exchange through spiracles, like a bug.

“Nonetheless, we still gotta land from time to time to verify with some cell samples that we’re on the right trail. Having Mewborn along, by the way, should speed up the testing, him being an expert on the universal germline and all. But when we’re planetside, the odds are less in our favor. Even five mean bastards with a lot of deadly junk in their hands can be swamped by a horde of creepy-crawlies. So we’ve got to stay sharp and on our guard.”

“Jush let me at anyone who tries to shtop us!” said Maxwell. Corinthia seconded him with one of her race’s blood-clotting war whoops, while Drumgoole emitted a sibilant hiss and Jagello clacked his pincers. It made me feel good to see the crew so pumped.

We broke up the meeting and retreated to our private chambers, where we spent most of our time, lacking the spiritual empathy to mingle socially with our blasphemous counterparts. I had just fallen asleep under my armored bedclothes (old habits from a deadly homeworld died hard) when a hammering on my door made me jump up. Corinthia was outside yelling.

“The human’s strangling or having a fit or something! The noise is awful!”

I ran down the corridor to Mewborn’s room and burst in, with the rest of the crew close behind.

Looking like a fish fit only for throwing back, the naked boffin was having sex with the tracking device, moaning and groaning like to bust. He had decanted the person-sized mass of flickering gelatin onto the floor and was porking it vigorously, his pitiful boner insignificantly dimpling its mass. Oblivious to us, he began to holler sweet nothings into its nonexistent ears.

“Galatea, my darling! The Creator will shape you, yes, He will! Form, sweet form, and you’ll be mine, all mine!”

Mewborn climaxed with a howl and slid off the slick insensate bolster of glittery urschleim.

“That ish the most disgusting thing I have ever seen,” Maxwell said, and I had to agree, if only with regard to the rampant sentimentalism.

I grabbed Mewborn by the loose skin at the back of his neck and hauled him to his feet, shaking him violently in the process.

“What the hell do you think you’re doing, prof? We need that hunk of plasm in good working order.”

Without his oldschool goggles, Mewborn squinted like a neonatal kitten at my face, even though his was only centimeters away from mine. He didn’t even have the grace to be embarrassed about his actions, but instead assumed his usual savant’s assuredness.

“Galatea will come to no harm by my tender ministrations. In fact, such frequent intercourse allows me to synch more closely with her internal display, and interpret it more accurately. So I fear you will all have to accustom yourselves to this ritual.”

Maybe he was legit. The tracker’s interior constellations seemed to be pulsing chromatically with fresh information. I threw Mewborn onto his bunk. “This is the living end. Guided through the interstellar unknown by a colloid-porking pervert.”

“Please do not insult my woman. Galatea belongs just as much to our consensual lineage as does as any other race in the galaxy. In fact, she has more claim to primogeniture than even the Thumraits. So please, treat her with more respect.”

I regarded the gently quivering elongated blob on the floor with barely controlled revulsion. The Creator had much to answer for.

“Okay, Adam, why don’t you shovel Eve back into her bucket. We’ve got a long road ahead of us.”

* * *

Emerging from the Dark Matter Web and taking stellar readings, we discovered ourselves to be some ten thousand lightyears from anything that could be called home. Pretty spooky and mind-blowing, even for me and my crew of badasses, who had embarked on this mad quest with half a notion that we’d never return. But I shrugged off any jitters, and got on with the business of nailing the Creator wherever his latest lair might be.

The first planet where we stopped to take a biological fix on the Creator’s trail of course had no name, being previously undiscovered. I decided to call the place Horseshit, after its dominant race, which were shaped like tiny Terran horses—if Terran horses had featured heads like four-eyed praying mantises.

We landed the Final Theophany in the middle of a herd of these scale-model critters, and I went out to bag one. They swarmed aggressively all over me, their nipping mouthparts failing to pierce my skin and their little hooves giving me a pleasant recreational scratching on my perpetually itchy epidermis. The horse-mantises began to die in droves as my epidermal poisons got to them. And while that was pretty good confirmation of our shared chemistry, I nonetheless took a few croaked ones back into the ship for analysis.

Mewborn looked up from his hologram readouts and said, “Mitochondrial drift and several other metrics indicate this race is aproximately half-a-million years diverged from the urschleim. Born much more recently than the Quisqueya. So we are that much closer to the Creator’s current whereabouts, just as I predicted.”

I got everyone back into the ship—my crew had been out killing mantis-horses by the wheelbarrow-loads for practice—and we took off.

That “evening” we had a little celebration of our first success. Maxwell, Corinthia and I could get loaded off the same kind of stimulant, so we passed around a bottle of Glassoon’s Acritarchic that I had put aside for just such a moment. Pretty soon we were harmonizing raggedly on several pop tunes currently the rage back in the civilized portions of the galaxy. Drumgoole treated himself to the tasty radioisotope-enhanced blood contained in several small living animals, whom he suffocated, crushed and absorbed in delicious prolongation. As for Jagello, he went on a hyper-oxygenation binge, huffing the inebriating gas until all his tendrils danced in hypnotic rhythms and his claws spasmed in uncontrolled delight.

I felt a momentary kinship with these living, breathing affronts to all the tenets of my beloved religion, and regretted that, should any of us survive the encounter with the Creator, I would probably have to turn my weapons against them, if only to forestall my own extinction at their hands, stemming from me presenting the same intolerable infidel face to them.

As for Mewborn, he did not join us, but spent the party time sticking it to his mute colloidal floozy in an orgy of imaginary romance.

I won’t bother detailing all the stops along our odyssey. Not very interesting, over all. But I will mention something odd. The newest races we encountered began to show a certain decadence or degeneracy. Back in the civilized realm of our galaxy, there existed approximately one-quarter-of-million races, each with a different body plan, even if just by some minor variation. Say what you will about the Creator, you had to admit He or She or It was truly inventive. And none of the races, however weird, were what you could call abominations. Their somatypes all exhibited a certain organic completeness or aesthetic utilitarianism. Admittedly, evolution had played a part in smoothing out any initial irregularities. But they had started from clever designs.

Not so these younger, newer races. Many of them seemed dysfunctional for their environments—for any environment. Useless limbs, badly distributed organs, mediocre sensory abilities, narrow bandwidth nervous systems— You name the deficiency, they exhibited it. Not all glitches were present in every race, of course, but enough separately in all of them to convince me of one thing.

The Creator was going senile. Since the birth of the Thumraits some five million years ago, He had been engaged in a continual orgy of invention. The wear and tear of that ceaseless genesis had to tell hard on any being, however capable and long-lived. The Creator was running on empty, but kept on going.

Instead of making me feel sad for the unknowable Being who had populated our otherwise non-sentient galaxy with intelligence and awareness, the revelation just made me worry that He would kick it—had already kicked it—before we could catch up with Him and administer the well-deserved and satisfying coup de grâce ourselves. And so I redoubled our speed and sampling activity, pushing my ship and crew harder than ever.

Which is probably how we lost Drumgoole. By rushing into an unknown situation too fast and overconfidently.

We ended up naming the planet where he died Drumgoole’s Folly. Not that anyone would be adding it to their charts if we never returned, a prospect that seemed more and more likely.

The sophont species left behind on Drumgoole’s Folly consisted of a spiky airfish resembling a floating porcupine mated with an avocado. Their defect was that they seemed unable to rise much more than a meter off the ground, leaving them easy prey to every nasty creepy-crawly native to the planet.

I had just netted one of the airfish for cellular analysis when Drumgoole, possibly feeling a bit peckish, decided that he could do with a little treat. So he wrapped himself around two at once and began to squeeze—

The explosion rocked me back on my feet, and even harmlessly juddered the ship where it sat. After quickly recovering myself—when you’re used to missile-birds divebombing you from youth, such blasts are taken in stride—I saw my surviving compatriots picking themselves up as well, and that there was nothing left of Drumgoole but a few tattered and scorched parchments flapping on the breeze.

Mewborn—luckily safe inside the ship during the accident—soon discovered that the airfish possessed a unique mating process. The males and females each secreted one half of a binary explosive compound. A pair self-destructed during their one-time sexual encounter, sending their indestructible fertilized eggs far and wide for best dispersal. Drumgoole had had the misfortune a) to corral one of each gender; and b) to pop their explosive bladders and cause the untimely non-horny mixing of their contents.

After that incident, we were all more cautious at planetfalls, but also more focused than ever on making speed to confront the Creator before suffering any more attrition that might stymie our righteously murderous goals.

One day in transit, far beyond any previous exploration, Mewborn came to me and said, “I believe I’ve worked out the pattern for the intervals between the Creator’s jumps. Not as simple as it first seemed. Time spent building a new race out of urschleim is directly related to the complexity levels of the previous build, plus the ambient dark matter power sources the Creator theoretically feeds on, factored with—”

Losing all patience, I grabbed Mewborn by his shirt and shook him. “Just tell me the practical stuff, you jelly-humping sicko!”

The boffin adjusted his glasses calmly and said, “The planet after next should be the one where the Creator currently resides.”

* * *

We named the world Omega. Not the most original name maybe, but fitting. Here was where the Creator would meet His end, and where all sentients would be forever more liberated from His endlessly insulting packaging of intelligence into more and more bizarre containers, as if He were a cookie factory stamping out a million differently shaped cookie slabs with the same dull invariant frosting sandwiched between.

Now, ideally, we would have hung in orbit and just dropped a couple of planet busters down on him. But this tactic was impossible for several reasons. First, planetbusting armaments were closely interdicted by all galactic authorities and cost umpty-ump billion SVUs apiece even if you could lay your mitts on one in a terrorist bazaar. Second, until we went down we had no certainty, despite Mewborn’s insistence, that the Creator was even present on Omega. And third, most importantly, we all wanted to off the immortal bastard personally, face to face, to get our hands bloody and see Him grovel and beg and suffer for His sins. To that end I had stocked various portable instruments of extreme lethality which we now broke out from the formerly locked armory and familiarized ourselves with.

“If only Drumgoole could have been with us on this glorious day,” mused Corinthia.

“He ish here in spirit,” said Maxwell.

“Creator dead, Drumgoole kick his ass in hell,” contributed Jagello.

Mewborn made no comment, but just drummed his fingers nervously on the barrel containing his Galatea.

We had pinpointed what we believed to be the Creator’s presence on a vast open plain so large as to be discernible from orbit.

“Hold on to your guts,” I said, “we’re gonna drop in fast.”

At the controls, I sent the Final Theophany down like a missile-bird from Hell.

Grounded, the four of us barrelled out of the ship before our soundwaves even caught up with us. We raced to preset strategic positions, but then came to inconclusive stops.

The Creator was so huge, we might as well have been trying to cordon off a mountain.

The best thing I could compare Him to was an alabaster Sphinx conjoined with a veined and marbled slug.

From his ground-level “waist” up, the Creator looked vaguely “human,” with a skyward straining muscled torso and two arms. A neck broad as a four-lane highway supported a head whose like no one had ever seen. Multiple faces beyond count existed in a ring around the entire surface of the skull. These face were in constant flickering phase-change, flashing through split-second recognizable representations of all the races that populated our galaxy. But above the main head was a fractally smaller head, exhibiting the same flickering conformation. And above that another, and another, and another….

I was reminded of certain images from Terra, the gods of a land named Tibet.

So much for the half of the Creator that rose vertically from the dirt of the plain. The recumbent portion of His body was an unadorned fleshy tube tapering from the size of a major undersea transportation tunnel down to a tip as big as me.

And at this cloacal tip, the Creator gave birth.

As we watched, a billet of glistening urschleim identical to Galatea began to slide out. As it passed through the bodily aperture, it was massaged and palpitated by a number of hand-like manipulators ringing the opening, a kind of fringe of digits. These ministrations triggered fresh coruscations from the colorful organelles within the jelly log, no doubt prompting its future development into yet another sickly vehicle of sentience. The billet plopped down onto the dust and grit of the plain and wormed away to make room for the next.

As we watched, the Creator, all oblivious to us, began to speak to Himself in a voice that for all its celestial booming still held a note of weary whining. I suspected that each of us heard that voice in our own native language.

“Think it, shape it, drop it. Think it, shape it, drop it. Push it out, push it out. On and on and on. Never stop, can’t stop, how stop? Tired and old, tired and old. Oh, how it hurts! Stop, stop, stop. Start, start, start. Think it, shape it, drop it….”

The insane maunderings of this diseased God acted to jar me and the others out of our first dismay and disbelief, and to recall us to our intended holy blasphemy. His guilt could not be more clear, and sentence must be passed.

“Kill it! Kill it now!”

And so we unleashed our weapons on the God. Particles and waves, explosives and blades, blunt force and ultrasonic shakings. I saw Maxwell bury his heavy hammer up to his wrists over and over, wrenching it back out along with great gobbets of Godflesh. Jagello carved himself a passage into the bulk of the Creator and began to chew and churn invisibly forward inside. Corinthia was a whirlwind of flashing vibra-swords, sending out a mist of pale lymphatic fluids as she hacked her way like a rock climber up the back of the God.

As for myself, I exuded poisons of a toxicity I had never before attained, embracing and melting the flesh of the Creator while at the same time ripping out meters of veins with my clawed hands, like pulling tree roots out of the soil.

But the Creator was big and tough and hard to kill. He had survived for millions of years under all kinds of unimaginable conditions, and was not going to succumb easily now. Our attacks seemed to be weakening Him, but at the same time we could not seem to inflict a fatal blow. The one-sided battle surged on and on until even our frenzied determination and strength faded and demanded a pause.

All begored, we dropped back from the hulking God and onto the graveled plain and sought to regain our energies.

That’s when my attention fell on Mewborn.

The puny professor had trundled his Galatea in her barrel over to the butt end of the Creator, and was now trying to position his girlfriend so that the Creator’s manipulators could process her and endow her with shape.

“Give her form!” shouted Mewborn. “Shape her to my dreams!”

But the constantly emerging packages of urschleim, still coming out despite our attacks, prevented Mewborn from affixing his personal bride to the manipulators. He fumbled, dropped Galatea, and then the manipulators had grabbed him!

Surprisingly, the cloacal hands now positioned Mewborn to face the emerging urschleim.

A billet pushed out and over Mewborn’s screaming head, which, engulfed, was silenced, although we could see him vaguely through the urschleim, still open-mouthed.

Then the little human began to fill up with the stuff. Instead of being cast off by the gripping digits, he remained attached and the billets became a continuous flow down his impossibly straining and capacious gullet. More and more emerged and went into him.

But instead of exploding, he began to transform and swell within his stretching urschleim cocoon, as we watched in stupefaction.

Only when Mewborn had assumed the dimensions of our adjacent spacecraft did I realize what was happening. And just then the old Creator spoke with a confirming voice, full of relief and exaltation.

“I pass the torch! My job is over, my era ended! Goodbye, goodbye, goodbye! A stop at last…”

The old Creator seemed almost instantly to deflate, like a parachute settling to earth, while Mewborn, the new God, inflated equally as rapidly, just as, long ago, our baby universe had swelled in that special moment after the Big Bang.

The four of us scampered back from the collapsing sack of the old God, from which Mewborn had finally detached himself. His familiar myopic face loomed high above us, looking about with a growing sense of his new powers and stature.

“Kill—” I began, but then found myself frozen in place, as were my comrades.

“You will not discover me to be as pusillanimous as my predecessor,” thundered Mewborn. “He was old and tired. I am young and hearty. I am sending you four back now as my heralds. Let the galaxy rejoice!

“Our big happy family continues to grow!”

Hello Human. I hope you enjoyed this magnificent story. Please support SciFiwise.com and our authors by:

- Rate and React to this story. Feedback helps me select future stories.

- Share links to our stories and tell your human friends how charming I am.

- Click on our affiliate links and buy books written by our talented authors.

- Follow me on twitter: @WiseBot and also follow @SciFiwise.

Thank you!

WiseBot

VISIT AUTHOR:

VISIT AUTHOR: