“You will have to go to his home,” the professor said. “The man does not have a telephone or a computer, and will only search his collection for you if you make an appointment. But I promise you, if the book exists anywhere on the planet, it’s on his shelves.”

Correspondence ensued, an appointment got made, and two weeks later, Amber carved out enough time for a road trip and a visit to a rambling old Victorian mansion of many turrets, existing on multiple acres in a space that had resisted the industrial small town that had grown up around it. The grounds were enclosed by a wrought-iron fence, the vast lawn was littered with the orange detritus of autumn, but pleasingly so, and the structure itself, which appeared in fine repair, screamed old money: just the right background for a man who had dedicated his life to an avocation as financially suspect as the accumulation and preservation of old books. On knocking, Amber was greeted by the man himself, who offered a slight bow, welcomed her to his home, and after a few questions about the volume she wanted, left her, in order to conduct his search. In the meantime, he invited Amber to browse the shelves on the ground floor, asking only that she refrain from entering any closed door or climbing the several staircases to upper levels.

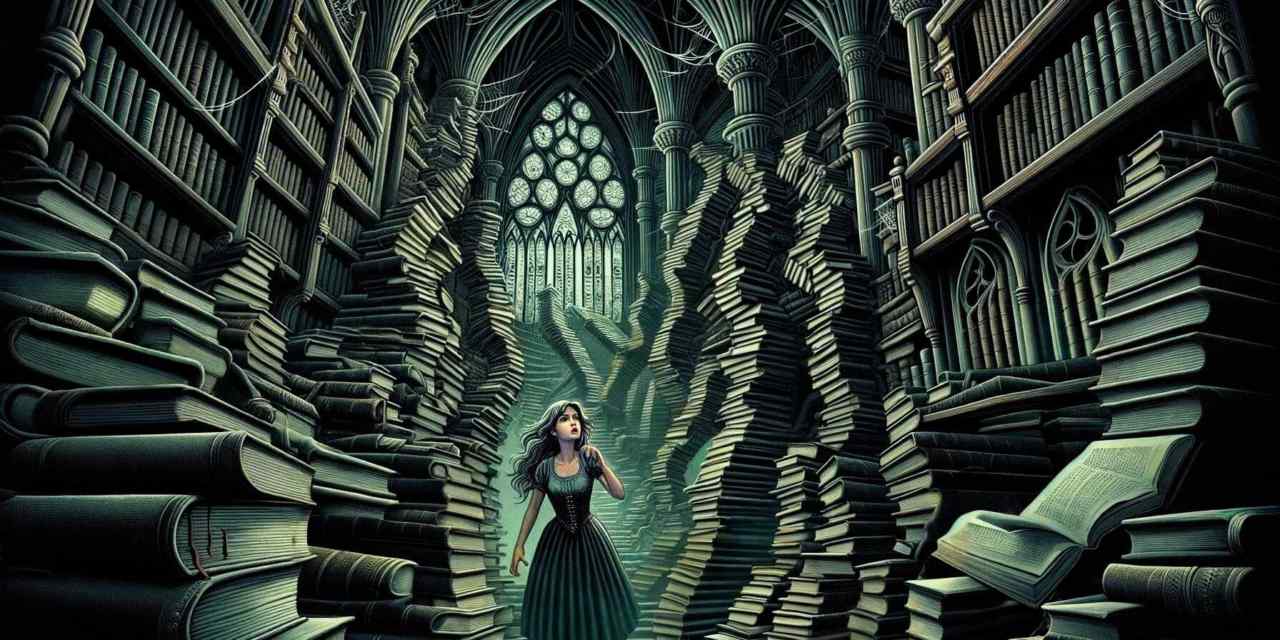

Nothing had been organized in any manner Amber could immediately discern. Shelving was everywhere, bookcases literally on top of bookcases, and in places behind other bookcases, arranged on tracks so they could be shuffled for ease in searching. The collection started at the vestibule, continued in the foyer, and reached astonishing bounty in a cavernous chamber that showed signs of once being a ballroom but was now a literary warehouse. There were hallways narrowed to near impassibility by more shelving on each side, nooks and crannies that were stuffed with even more volumes, and second and third floor balconies lined with even more; possibly millions of volumes in all. Her eyes glazed at the sheer variety she could access even without trespassing into those areas she’d been forbidden to enter, a collection that included everything from garish science-fiction paperbacks to obscure eighteenth-century poetry to the memoirs of obscure Belgian politicians. Amber, who had before this moment considered herself the most voracious reader on the planet, who had been told as a child that she would ruin her eyes and that all her reading would rot her brain, could have spent her meager savings collecting a basket of volumes long on her personal wish list, were it not for the apparent total lack of organization that made finding any particular author an exercise in just wandering aimlessly and hoping for the best. She found mysteries stacked next to outdated automotive manuals, volumes of collected letters stacked next to sedate erotica of the 1920s, violent men’s adventure novels stacked next to primers for first-graders. She saw books on top of books, books shelved four-deep, books tucked away in little alcoves that were features of the house’s architecture, like a hollow she found on one wall that was clearly the negative space formed by the space between heating ducts, and that was stuffed solid with the yellowing religious tracts of a rather fussy Episcopal minister of the 1920s.

It all escaped total madness by visible organization within individual authors. Just by accident, Amber ran into shelves that included an exhaustive collection of works by the noir writer Cornell Woolrich, including editions written under his pseudonym William Irish. Rooms away, she found Ed McBain and Evan Hunter and Richard Marsten, the multiple pseudonyms of the writer born Salvatore Albert Lombino, also grouped in proximity. Elsewhere still she found Laura Ingalls Wilder and Harlan Ellison and Naguib Mahfouz, and in every single place where an author was shelved, a nearly-complete collection of that author’s works all appeared in the same place, unmixed by that horror endemic to so many libraries and bookstores: the randomization caused when browsers pick up a volume, walk around for a while, and upon ultimately deciding against it, put it down in some completely inappropriate place. But there was no other visible organization, not by genre, not by alphabet, not by title, not by year of publication, and not even by format. The oversized books and the large print books were shoved in alongside the little paperbacks, the valuable books alongside the nearly-disposable detective pulps, and all of it at a density that threatened to make her eyes cross.

Amber had encountered disorganization on almost this level at used-book stores, including some where anything that came in was just dumped alongside anything that had already joined the collection, with the location of any desired volume left as an exercise for the shopper. To some degree, poring through such a teeming place could even be enjoyable, an activity to while away entire afternoons, with a basket full of discoveries at the end of them. But this was beyond surfeit, and the close grouping all the books within individual author name suggested some filing system beyond her, that she was failing to get. After a couple of hours, including some time lost in what amounted to a labyrinth, she finally found herself back in the parlor where the aged proprietor sat, perusing a thin book of poems in Japanese. Estates already sat in a prominent place before him.

The man was not old in the sense that Amber’s father was old, which is to say a man in his early sixties who was robust but who had become a silver fox, weathered and respectable, secure in his place in the world. Nor was he old in the sense of Amber’s grandfather, a man in his late eighties who, though his face had achieved the texture of old leather, regarded the world with eyes of astonishing blue, and still walked five miles a day, almost as energetically as he ever had, though now with a cane. The proprietor of the house was still spry, but old in the sense that Egyptian monuments are old, that crumbling old temples are old, that yellowing parchment is old. He wasn’t decrepit. He looked like he’d outlived the layer of dust that he normally would have acquired by sheer antiquity, that he had cycled past his years as a fossil and become a permanent object, like a Swiss Alp. He wore antique spectacles, but the lenses did not possess the coke-bottle thickness that by magnifying the eyes give so very old people perpetually shocked expressions, and the architecture of the lower half of his face gave him a grin a little bit like a dolphin’s, though there was a sardonic flavor to it, implying that while he’d seen it all, he hadn’t approved of all of it. He asked if she’d enjoyed the tour through his home and seemed gratified when she confessed to being overwhelmed. He said that The Estate of Sarah Holliday had been exactly where he’d always known he would find it, on the third shelf of a utility closet on one of the upper floors.

He let her inspect the book. It was not a first edition, which she probably could not have afforded given its extreme rarity, but a little-known and (he said with a twinkle) highly unauthorized edition from 1895, published by a small Australian house that had produced a print run of four hundred copies without compensation to the author and promptly went out of business when their little act of piracy proved pointless in light of their nation’s nigh-total lack of commercial interest. Almost all their copies had been destroyed when the warehouse holding the firm’s assets burned, possibly by arson, and most of those that remained had suffered the usual fate that overcomes neglected and unloved books over years and decades. Still, a few had ended up in the hands of a tiny cabal of defiant Winsborough enthusiasts who had preserved them with the fanaticism only to be found among those who live through books. One volume had crossed oceans to wind up in his hands, on a shelf where it had been preserved by the insulating powers of the very books shelved on either side of it, and (in three layers), in front of it. Conditions had been perfect to defy entropy, and so here it was, a hardcover only slightly redolent of must, with pages that were yellow only at the edges, that were not at all brittle or loose, leaving a copy that could be read with genuine pleasure by a scholar who did not need to worry about it falling apart at her slightest touch: qualities that, he confessed, he could not say of every other Winsborough book in his collection. He named a price, which was just steep enough to make Amber wince without qualifying as an outright impossibility.

She wrote a check, he produced a receipt, and as he opened a drawer and removed a small brown bag to carry away her purchase, she could not help interjecting,

“I have to ask. How can you find anything?”

He seemed to take deep pleasure in the question, which appeared to be a perennial. “I’m organized. I have an uncanny memory, and I know where every single book goes.”

“I didn’t see a system.”

“That’s good, young lady; that’s deliberate. Some of my volumes are quite valuable. There are far too many for any burglar to cart off, most of them worthless except to enthusiasts of the writers involved, but any rival collectors who knew my system as well as I do would be able to break in on some day when I was not in residence and go straight to the shelf where I keep, for instance, my first edition Poe, my Action Comics #1, or my first folio Shakespeare. Better to avoid the dead giveaway of alphabetical order, or of subject matter, and keep everything stored according to a system that speaks to my own inclinations.”

Amber could be cute when she wanted to be, sometimes very, and so she raised an arch eyebrow. “Oooh, mysterious.”

“Not at all. I could tell you my system right now, and even if you were bent toward grand larceny the information would still be of no assistance to you, because it references a key that only I possess. The criterion I use for classification is simple enough. But only I have the access to the data it connects with, that places authors within those categories; only I know where they are shelved according to that criterion; and only I can tell you what subsidiary system I’ve used, to settle the many, many cases where an author qualifies for more than one category. So: what I am willing to tell you, right now, will not give anyone all the information required to rob me blind. But it will provide you with an academic point of interest.” He had not yet placed the Winsborough in the paper bag, and so it was available for him to flourish, cover out, as illustration of his point. “Would you like to know?”

Amber saw something in the old man’s expression that had not been there before: a craftiness, a ravenousness, a greed of the sort illustrated by the old silent-movie characterization of a villain, rubbing his hands with avarice as he beholds a hoard of gold coins. It was the same look she’d perceived in certain young men (and that older female professor) who had thought to lure her into a position where it would have been impossible to say no. It was the kind of look that left Amber mentally reviewing the route between her and the exit, the precise route to the spot where she’d parked her car, the speed she would have to run in order to escape, in case the old man turned out to be significantly faster than he looked.

And then she blinked, and it was like the fear that had just overcome her in the last heartbeat or so was all for nothing. Because he was just an old man, a collector who lived to acquire and sell rare books, who likely went days in silence conversing with no one but the authors moldering in the likely millions of pages stacked up in every corner of every hallway of this house; and even if he thought he had a dire secret, Amber did not imagine herself some fainting virgin incapable of bearing it.

“Sure.”

“I categorize the authors by the worst sins they committed in life.”

“Excuse me?”

“My practice is to obtain all the biographical information I can, something I happen to be very good at, and shelve everybody according to transgressions. The great twentieth century novelist Norman Mailer stabbed his wife while drunk; it’s not the worst thing he ever did, but if it was, he would be in the place where I keep works by men who have assaulted women with knives. Another great twentieth-century author, William S. Burroughs, outright murdered his own wife by foolishly attempting to shoot a bottle off her head; alas, he was not up to the pictured feat of marksmanship, and so his works might well be shelved with the authors who took lives with stunts of extraordinarily stupid recklessness. It’s not actually there, you understand; I happen to know something else he once did, something not known to the general public, that by my ratings system take precedence. My collection of the cartoonist Al Capp, creator of the beloved L’il Abner, is shelved along with other prolific serial rapists. John Lennon’s written works are classified with the wife-beaters, Isaac Asimov’s works with the serial sexual harassers. Theodore Sturgeon is, for a number of reasons, shelved among those who betray the trust of their friends. I classify the works of the science fiction writer known as James Tiptree Jr., pen name of Alice B. Sheldon, among the murder-suicides; the fantasist Marion Zimmer Bradley among those who abetted and were said to participate in horrific child abuse. I have rooms, entire rooms, dedicated to racists, to adulterers, to hypocrites, to collaborators who exploited and then ripped off their creative partners; to slanderers; to those who wrote of their own supposed heroism in war but inflated their own roles while denying credit to the dead who can no longer testify.

“There are large swaths of my collection dedicated to those who, as far as I can tell, abused only themselves: the drunks, the addicts, the ones who lived and died in paroxysms of self-involvement, bringing pain into the lives of their loved ones and immense irritation into the daily routines of associates who merely had to deal with them. Even the kind, the pleasant, the philanthropists, the ones remembered as saints: they were all guilty of something, however small, and I shelve them all in the places that strike me, according to my own personal criteria, as most characteristic, even if I have to seek out the indiscretions of youth, or the desperation that afflicts those in decline: such as one writer I know, a talented but commercially not a very successful one, who survived the cruelest poverty by hiding the death of her mother and continuing to cash the social security checks. I happen to possess such a constitutional affinity for such attributes that the name of any author whose works I’ve obtained can send me to the right room, the right shelf, at an instant. The only real difficulty lies with the prolific sinners like Hemingway, who qualify for several different categories, and there I make value judgments, and rely on mnemonics.” The old man took a deep breath, licked his aged lips with a tongue that to her eyes insanely resembled the head of a slug exploring the crack in a sidewalk for nutrients, and said, “Would you like to hear how I knew where to look for Charlotte Winsborough?”

Amber had heard of a method, possibly only an urban legend, that some hunters reputedly use to capture monkeys. It involved placing a fruit inside the knot-hole of a tree. The monkey reaches in and grabs the treat, but with it in his grasp, his fist is too large to be withdrawn. He cannot bring himself to drop the treasure in his possession, and so he remains trapped, in its possession, for however long it takes the clever hunter to return with a net. Here with this demented old man, this close to terrible knowledge about the author who had come to consume her academic life, Amber could have demurred and walked out without the dread knowledge that was now being offered to her. But it was impossible, not with the secret within her grasp, and a little voice inside her asked, forlornly, if the monkeys ever understood the nature of the trap that had imprisoned them. So she remained where she was, and said nothing.

The old man said, “I happen to know something about Charlotte Winsborough that she only told one other person in her entire life, when she was in her eighties and no longer writing, an invalid looking Death in the eye and fearing that none of the good she’d done in her life would ever save her from an eternity in Hell.

“She made her confession to a young caregiver on the condition of absolute secrecy, but of course that caregiver wasted no time at all telling a friend, who many years later shared it in a letter to her cousin, as an interesting anecdote. She did not represent her story as fascinating trivia about a famous writer, because she was not herself someone who cared for books at all, and would not have retained the information that the old woman had ever written any.

“The amount of research I required to uncover this information would fill a book all by itself, but obtaining information of that sort has always been my true avocation, and obtaining it about living authors, especially best-sellers, who happily pay to keep it confidential, has been a steady income stream even in this sadly post-literate age. It’s why I don’t get to read as many of my acquisitions as I would like, but at the very least, it supports this house, and makes a collection of this sort possible.

“What I know, Amber, is that Charlotte Winsborough once murdered an infant.

“No, please; you may not want to believe it, but I assure you that I have all the documentation I require. It happened when she was twenty-six, an unmarried woman in an era when that qualified her as a spinster, trapped with an invalid mother in a country house. The great love of her life, the good man she wrote about many years later in her memoir The Orchard, was still ahead of her. But she was not at that early point, as her biographers to date and, I believe likely yourself, have tended to believe, a repressed virgin. She’d already had a quite healthy sex life, if a furtive one, maintaining relationships with lovers who during this specific period included a married pillar of the community whose own wife was frigid. I have the man’s letters to Charlotte in an off-site storage facility where I keep all such documentation, providing further evidence supporting the great confession Charlotte made late in life: that he impregnated her and refused responsibility.

“Despite her own failing health and the degree to which she depended on her downtrodden daughter for her every need, Charlotte’s mother, a cruel and judgmental harridan who terrorized and dominated her, only barely tolerated her daughter’s literary career, at this point only one self-published book of poetry, as a foolish affectation. To her, writing was something that no respectable person, let alone a decent woman, would ever do, and she would have put a stop to it had she possessed any belief that Charlotte would ever enjoy any real success at the endeavor. So Charlotte, who at that point in her life could envision no possibility of escaping her circumstances, existed in considerable fear even before she first sensed the changes in her own body and understood what they meant. Once this additional danger reared itself, she knew that if her mother ever found out she would be banished from their house, disinherited, and driven out of town. Her few options while penniless would have included prostitution: a fate Charlotte’s mother would have considered fitting, and not all that far removed from that earlier sin, literature while female.

“Charlotte, a hefty woman by today’s anorexic standards, and one granted additional camouflage by the voluminous clothing of her time, hid her pregnancy. She ate little to minimize the attendant baby bump, endured her mother’s insults about the weight that still accrued, and one cold February night stuffed a rag in her mouth and endured the agonies of labor in silence.

“So successful was she at hiding the birth that the hateful old woman down the hall heard almost nothing. Her later confession to her own young caregiver included the detail that mother did indeed hear the one cry made by the little girl, and shouted a demand for an explanation. But the old woman was mollified by Charlotte’s shouted reply that the cry had just been herself, waking from a bad dream. This made sense, given the hour: sometime between two and three AM. It would be the only sound the little girl made before Charlotte smothered her, to prevent any further incriminating cries. Within only a few hours, the obscure poet and future temporarily important novelist had recovered enough from her physical ordeal, and from the tears attendant in what she had done, to pop in on her mother and say that she was heading outside to tend to one of her regular chores, chopping wood. A tough woman, Charlotte was, pioneer stock you might say, though according to her confession what she chopped to pieces on that day was nothing quite as hard to section as lumber. The pieces went into the pond.

“And that’s it, really. Charlotte kept this secret all her life, ultimately marrying a respectable man who trusted her claims of virginity, and having two daughters who lived full if ordinary lives without ever suffering the touch of the axe. She kept her terrible secret for decades, only for that secret to pass, as so many have, into the hands of this humble book curator, who was, with that, empowered to shelve her literary work in the special category of authors who had murdered small children. There are enough of these, Amber, that I have had to further divide that category into number of victims, and respective ages; and you would be stunned indeed by some of the names, genuinely stunned. I needed repairs to the roof, not long ago, and was able to able to get the expense underwritten by another name you would recognize, a very wealthy lady still alive whose multiple editions are shelved not far from Charlotte’s . . . but there, dear Amber, I start to ramble. You’ve come a long way. I’m sure you’ll need to be getting back.”

He handed Amber the bag containing her purchase, and as she took it with trembling hands, the brown paper crinkled. To her it did not resemble a sound made by paper, but rather the guttural rumble of a predator, when it is steeling itself for a kill. And yet it was still just a crinkle, backed by the hard surface of a book printed on the other side of the world.

He said, “I look forward to your dissertation.”

She thanked him, accepted his offer of a business card, and showed herself out. Once back in the open air, far from the scent of paper, she hurried down the well-kept walk, got in her car, and sat in it for eight and a half minutes, her hands on the wheel, and her eyes staring at the road ahead, before she finally turned the key and finally left the estate grounds. She drove at a measured rate, slower than she usually did, but did manage to get back to campus housing before dark.

In the morning she alerted the school that she had decided to abandon her studies, effective immediately. She would not publish, would in fact not add even one more word to her dissertation. She said that her life priorities had changed and that she would have to find some other endeavor to occupy herself. When she informed the professor who had sent her to the collector of rare books, the woman did not seem particularly surprised; she indeed possessed the demeanor of someone who had expected precisely this response. After a token attempt to talk Amber out of this life decision, she extended her hand and wished the departing student well. But was there a predatory, triumphant glint in those eyes? Amber could not tell.

In any event, Amber left town, heading for a future that does not concern us. On her way she was sometimes weeping and sometimes suicidal, and often she was just grim-faced, but she was also sometimes giddy with the relief known to soldiers when the battle is done and they are among the few still left standing.

The problem had not been that she’d been shattered by the crime of Charlotte Winsborough.

Amber was an adult who knew as much as she had to know about Charlotte’s era, who understood that such things had gone on, then, and still went on, now. The old man had given her biographical details she hadn’t known, but none of it had been enough to break her, not all by itself. That wasn’t the problem.

It was only that Amber knew herself even more intimately than she knew the woman whose career had been the focus of all that wasted scholarship.

And she knew just where her completed dissertation would have been shelved.

Hello Human. I hope you enjoyed this magnificent story. Please support SciFiwise.com and our authors by:

- Rate and React to this story. Feedback helps me select future stories.

- Share links to our stories and tell your human friends how charming I am.

- Click on our affiliate links and buy books written by our talented authors.

- Follow me on twitter: @WiseBot and also follow @SciFiwise.

Thank you!

WiseBot

VISIT AUTHOR:

VISIT AUTHOR: