Grandmother’s rocking chair is made of iron. It is rust and death and blood. Grandmother’s rocking chair sits in the middle of the porch so that she can watch me and pet her turtle. Tortoise, really. It is as old as Grandmother and waits patiently by the chair like an end-table of shell.

I play with a toy soldier and his tin horse under the shadow of the tortoise in the summer heat, careful not to let my fingers pass under the cutting blades of Grandmother’s rocking chair. She rocks back and forth, slicing grooves in the hard oak of the porch.

The rocking stops. Grandmother reaches a hand down and taps my calf where I’m sprawled on the porch. “Child—” We are all “child” to her. “Child. Go see if the mail has come.”

Still holding my tin horse, I push back out from under the tortoise, and it turns its slow eye toward me. I scratch the leather head and frown at the road. “Did you see the mailman?”

“Go on now. No sass.” She smacks my rump, and the rocking begins again.

There is not a mailman. There is no mail. There has never been either on any day that I have ever gone to check the box. But I go because Grandmother’s chair is made of iron. It is rust and death and blood, and she is my Grandmother.

I don’t want to make her ask thrice.

On bare feet, I hop across the ruts in the wood of the porch that her chair has sliced. You have to be careful not to slide your feet on Grandmother’s porch, or splinters drive deep into the soles. All of us have left bloody footprints on that porch.

Bounding down the stairs, with my dungarees rolled up nearly to my knees, I squint as I come out into the sun. Grandmother’s yard is made of stone.

It is dust and grit and the long, long dead. The dust blows in little spirals that follow the shapes of ammonites buried in the stone. A sidewalk cuts through the stone in a straight line dead-ending at the street.

The sun has baked the sidewalk hot, and it scorches my feet as I run on tiptoes to the mailbox. I said the sidewalk is straight and that is true until it passes under the shade of the only tree. The massive oak there has lifted the sidewalk up into a hill, tilting the pavement to the side as if it is going to tip you down into the stone yard.

I slow as I pass under the tree. I clamber over the sidewalk hill and out to the street.

The street is made of dirt. Red clay. Gravel. From the porch, in her rocking chair of iron, Grandma calls out. “Don’t go into the street. You hear?”

I stand on my toes at the end of the sidewalk and lean out, to open the mailbox.

“I said, did you hear me?”

“Yes’m.” I will not make her ask thrice.

The box is hot, even in the shade of the only tree. A layer of grit roughs against my fingers. I tuck my tin horse into the pocket of my dungarees. With one hand, I hold onto the iron post at the back of the mailbox and lean out to reach inside without putting a foot on the dirt road.

There is something inside.

I jerk my hand out. An envelope falls from the mailbox. The envelope is made of skin and tattooed with an address that I have never known. It lands in the road, and the red clay dust brushes over it.

My heart kicks like a goat in a cage. There’s a letter. The mail came. “Gra— Grandmother?”

“What is it?”

I crouch at the end of the sidewalk, my arms resting on my knees and squint at the envelope. It is pale cream, and about the size of Grandmother’s palm. Red dust brushes over the surface.

“I said, what is it?”

“It’s a letter.” Never make Grandmother ask thrice. “There ain’t no stamp.”

“Bring it here.”

I reach for the envelope, because I want to know what’s in it and because Grandmother has asked me to.

A breeze snatches the letter and hustles it farther into the street, and without thinking I step forward. Off the sidewalk. I step into the street.

Behind me, Grandmother screams. The sound of the rocking chair stops. Dust and grit coat my feet and scratch my skin. I snatch the letter up and turn.

Grandmother’s house is gone.

* * *

The road is made of rust. The rough red dust blows over my bare feet, hissing up the legs of my dungarees and chafing the skin at the backs of my knees. I clutch the letter in both hands and hold it over my head for the little bit of shade it offers. The sun scorches the road and the bare earth on either side, differentiated from the red of the road only by parallel lines of smooth round stones, all alike.

The stones have wiggly cracks along the domes, almost like the tortoise, but they are bone white.

I have not opened the letter yet.

I turn in a circle, but the horizon is unbroken. Wetting my lips, I walk back to the edge of the road where I think I stepped off Grandmother’s sidewalk, and crouch down, peering over the line of stones. The dust hisses over their bone-smooth surface. I’m scared to step across them.

Biting the inside of my lip, I bring the envelope down and look at it. The envelope is made of skin, and the address tattooed on it says:

Mother

Restless Track

Nowhere

The stamp is a shilling buried under a blob of blood-red sealing wax. On the back flap is another blob of sealing wax, gone glossy with the heat. It would open easily under my hands. I tell myself that maybe it was meant for me to open or that maybe if I don’t break the seal, no one will know if I open it.

I know better than that.

But I also have nothing else to mark my spot with, so I peel off the edges of the wax around the shilling and press it against the stone. Except when my fingers touch it, I can’t keep pretending that it’s stone.

It is a skull. All of them are skulls, stretching out in parallel lines as far as I can see in both directions.

Careful as I can, I tuck the envelope into the front pocket of my coveralls and bump into something hard and uneven. I reach into my pocket and pull out my tin horse. My tin horse is made of tin and black flaking paint. I turn her over in my hands and wish I had brought the captain with his gold feather and his canteen or the leftenant with his rifle, even though the bayonet is snapped off.

I want a grown-up with me to make decisions about which way to go. A road goes between two places, and I have to choose which way to go. Do I go to where the wind is coming from, or where it’s going to?

I look at the red road again. Either way, I cannot see the end of the road, and I tell myself that Grandma would not want me to be alone, but I know that’s not a real reason. A tin horse is just a tin horse, no matter how big.

I bite down on the side of my cheek until I taste blood and spit a red globule on the tin horse. Once, twice, thrice, the spit coats the horse. Then she is too heavy in my hand and then in three breaths, she is standing beside me on the rust-red road, with three red stains on her black coat, like bullet wounds.

She tosses her head, mane blowing in the wind. Her saddle is made of tin and the stirrups jangle, waiting for me.

I show her the envelope. It has what must be my grandmother’s address. “Do you know where this is?”

The horse rolls her eyes and snorts. Now I wish that I had pretended she was a talking horse, but it is too late for that. I tuck the envelope back into my dungarees pocket and clamber up into the tin saddle. The reins are molded to the saddle, but at least they are leather. Mostly. I gather them up and turn my tin horse to look at where the wind comes from.

It whispers, spitting sand into my eyes when I look along the road. Maybe it’s nonsense, but the letter had to come from somewhere and so does the wind, so I squint my eyes and kick my tin horse in the sides. With a dull clang, she moves and we walk into the wind.

* * *

My horse is made of tin. She has a coat as black as paint and the sun makes her as warm as a living thing, but when I kick her sides with my heels, she clangs. We have been riding under an unmoving sun. The only things that change in this landscape are us and the rust-red dust borne by the wind. My head sags against my chest, but my tin horse never tires.

The heat makes my head ache from the glare and the heat. My eyes drift closed.

I jerk awake as I am falling. Too late to catch myself, I see the black and tin side of my horse, and then the red-rust ground slams against me. I cough. My entire side feels afire with pain.

My tin horse stops. She looks back and waits as the breeze stirs her stiff mane and tail into windchimes.

For a minute or an hour, I lie there in the dust and wait for the burning pain to subside. It is tempting to let my vision fuzz out and stare past the line of skulls at the horizon. Grandmother would scold me if she were here.

Spitting oxide dirt out of my mouth, I sit up and wipe a hand rough with grit across my face. I stare across the line of skulls, and a spot of red catches me.

The dome of the skull closest to me has a blob of soft red wax stuck to it. I scramble on my knees and hands to the skull. A thumbprint dimples the red wax, and you can just make out the impression of a shilling’s ridged edge. The wax I left.

No.

I look back the way we have come from, and the road is empty of tracks. The only ones are in this little stretch here and the few that my tin horse made after I fell.

No.

We have gone nowhere. The wind steals my breath. I ball my fists into the cloth of my dungarees. It isn’t fair. There ought to be somewhere to go or to come from. What’s the purpose of a road that doesn’t go anywhere?

I reach into my front pocket and pull out the envelope. It came from somewhere. I know where it was going to, but not where it was from or who, and there’s a way to know that.

So I open the envelope.

The wind stops. And then it changes directions.

* * *

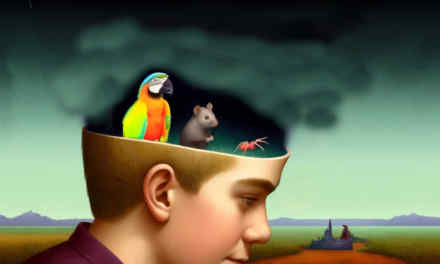

The wind is made of memories. Some of them are mine, like the memory of building a kite with Grandmother and flying it over the hog pen in the backyard as that wind blew the stink of them away from us. Some of them are not mine, like the memory of flight that comes skidding over the rust-red road as a flurry of bright blue feathers.

They swirl through the air, flashing blue, black, iridescent. For a moment, the red rust vanishes, and all I see are feathers and blue and black and the memory of stars. They flurry away, and the road is unchanged.

“Child.” The voice is behind me, where the wind had come from. A woman, her voice low and purring, asks, “Have you brought me a present?”

Something small and metal smacks against flesh. I swallow and turn. A woman with wings of iridescent blue stands on the road. Her wings stir the dust, sending a different wind skidding across the road. She tosses a tiny tin horse in the air.

“That’s mine.” My voice is small against the wind of her wings.

“Is that so?” The tin horse flies in an arc, tumbling back down to land in her palm. “I found it lying in the road.”

“My grandmother gave her to me.” I hold out my hand, palm up, and stick my lower lip out to keep it from trembling. It does anyway. I lift my chin. “Give her back.”

My horse spins through the air again to land in the woman’s hand. “Where is your grandmother?”

She might still be on the front porch of the house she never leaves or she might have gone inside or maybe, maybe, maybe she has left the house and the yard and is looking for me. ‘I dunno.”

“Oh good. Then why not come home with me?” She steps to the side and fans her wings back. Behind her, the road has changed. It ends someplace now. On the horizon is a spot of green so vivid that it aches. I’ve seen the deep green-brown of the tortoise’s shell and the pale, soft green of the aloe plant in Grandmother’s kitchen window. This is a green as bright as blood is red.

If I know anything from the plants in Grandmother’s kitchen window, it’s that you have to feed green. In a place like this, with the wind and the dirt of rust red, what would make something be so green?

I take a step back. “Who are you?”

“You have my letter.” She stops tossing my tin horse and closes her away inside her fist. Her eyes glitter with a black as dense as the blue of her wings. “Why not read it?”

I don’t mean to. I opened it because I was frustrated and tired and now, reading it seems like the last foolish thing before death, but my eyes glance down of their own will, and the words tattooed across the inside of the skin envelope claw their way out.

Give me back my child. I’ve waited the seven years you demanded. Give my child back or I will cut the heart out of the tortoise and use its shell for a boat to send you to hell in. Give me back my child.

“Don’t you hurt the tortoise!”

She pouts, tilting her head to the side and her wings stir the dust of the road. “I don’t want to.” Then she smiles as if the pout had never been. “And now that you’re here, I don’t have to.”

* * *

My mother is made of feathers. My mother is made of feathers and hate and love. I can see the hate in the letter and the love in her eyes. She takes a step toward me, still clutching my tin horse in her hand. “Child… Come home with me.”

“No!” I turn my back on her and scream along with the wind escaping from her wings. “Grandmother!”

The wind kicks up, snatching my voice from the air and mixing it into the rust-red dust. I look for the skull with the wax on it and start towards it. I think I might jump the skull and take my chances in the endless land, because Grandmother might be on the other side. I know better, but I am too frightened and angry to stay still.

My mother’s hand lands on my arm. Her grip is made of iron. She yanks me back and jerks me around to face her. Wings block out the sky and her face leans close. Fine, smooth, white feathers cover her face and her hands and do nothing to soften her. Her blood-blue wings flex, filling the air with cinnamon.

“Child. Come home with me.”

“No!” I tug at her unyielding hand. “I want my grandmother!”

“She’s a monster.” Her grip tightens, and the feathers on her face fluff. “Just say you’ll come with me.”

The way she says that, my thoughts jump into place like a tin horse coming to life. She needs me to agree to come with her. She can stop me and frustrate me and steal my tin horse, but she needs my permission to take me home with her.

I ball my fists and stomp my feet. “No! I want my grandmother. I want my grandmother! I WANT MY GRANDMOTHER!”

The wind stops.

* * *

Grandmother’s rocking chair is made of iron. Her steed is made of shell and bone and leather. She holds the rocker rails in her hands, and they are long, curved swords. She sits astride the tortoise, and blood drips from between her fingers, where she grips hilts as curved and sharp as the tips.

“Let go of the child.”

“I did once and that was a mistake.” My mother draws me back toward her.

“I asked you thrice if you were sure.” Grandmother’s head is low and forward. Her blood drips onto the rust-red road and vanishes into the dust. “It may have been a mistake, but it was also a choice. Choices aren’t so easily undone.”

“As if the child had a choice of where to live.”

“I was called, wasn’t I? Thrice. And that was enough to follow.” She flexes her fingers on the hilt made of blood. “Child. Do you want to go home?”

I nod.

My mother pulls me closer. “Home is with me.” She grabs me with her other hand, and my tin horse falls to the ground beside us.

I bite the inside of my cheek and spit blood on the tin horse. Once. The spray blends with the sand. Twice. Blood dribbles on my chin. Thrice. The black paint coat is as red as the dirt. My tin horse swells and rears with a snort and a whinny that sounds just the way I had imagined it would under the tortoise on Grandmother’s front porch.

As her hooves arc through the air, she comes down on my mother’s hand. Her tin shoe just barely brushes my arm, but cracks into my mother’s hand. I twist away, grabbing the tin horse’s reins with my free hand. When she rears again, I go with her, dangling like a toy soldier on a kite string.

Grandmother and the tortoise lumber forward. I see her pull her swords up and back, sweeping like wings into the air. My tin horse’s hooves touch the ground and I press my face into the metallic sweat so that I cannot see. But I can hear. I can feel. I can taste.

The wind hisses. The sand spits and swirls and becomes wet spray. The tang of copper and iron sneak past my clenched lips.

And the wind stops.

“Child, don’t look.” Grandmother’s voice is rough and made of sorrow. She puts her hand on my shoulder. “Home. We’re going home. I’m taking you home.”

* * *

I sit in grandmother’s lap on her porch and my tin horse stands in the yard of ammonites, pretending to eat grass. We watch her, as grandmother holds me close and we rock in her chair made of iron.

Hello Human. I hope you enjoyed this magnificent story. Please support SciFiwise.com and our authors by:

- Rate and React to this story. Feedback helps me select future stories.

- Share links to our stories and tell your human friends how charming I am.

- Click on our affiliate links and buy books written by our talented authors.

- Follow me on twitter: @WiseBot and also follow @SciFiwise.

Thank you!

WiseBot

VISIT AUTHOR:

VISIT AUTHOR: