My feet are scraped and bleeding, my slippers shredded and almost useless. The dress hangs in tatters around me. No longer white, it still bears the pearls along the bodice, and I hope I can keep them close and sell them in whatever town I find myself in.

Provided I find a town. Provided I ever leave these woods.

I have traveled for two days, surviving on puddle water and berries, hoping that the sounds I hear behind me aren’t my father, Roland, and the dogs.

***

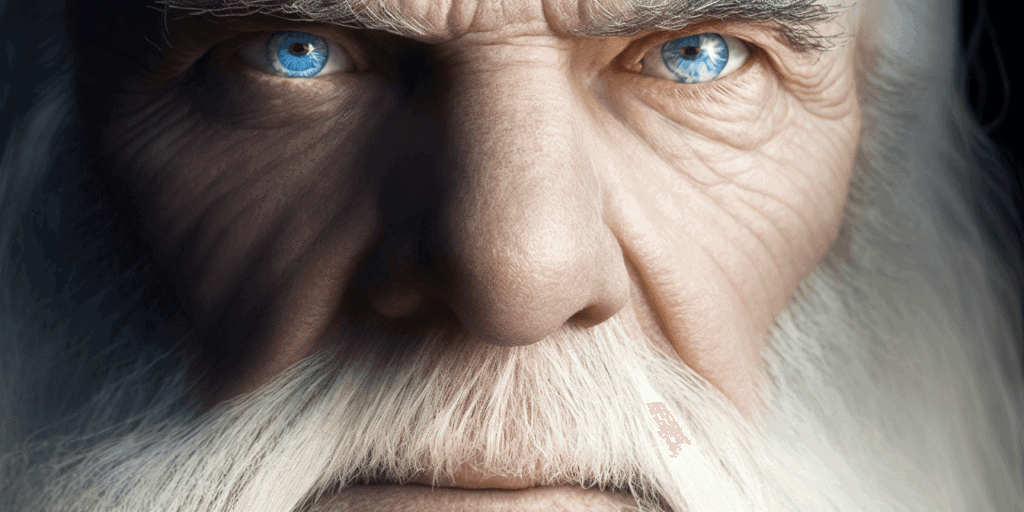

I was but a child when Sutton came to the Keep. He seemed like an old man even then, with a beard that trailed to his knees and white hair that fell about his shoulders. His fingers were long and fine, but his back was broad, like a laborer’s, and his skin was rough to the touch.

His eyes frightened me. They were a pale blue, so pale that, in a certain light, they seemed clear. When I mentioned them to my mother—she was alive then: alive, vibrant, and beautiful—she laughed.

“Of course, Micheline,” she said in her lilting accent, using—as she always did—her people’s version of my name. “He is magic. It is fitting he has devil’s eyes.”

My father said my mother was a witch, but she had no true magic powers. She knew the gentle arts—herbs for healing, mostly—and she had an enchanting laugh. Men were drawn to her, and women too. She had a personality that overshadowed all others, and dwarfed my father’s.

Apparently my father had once loved her. Perhaps he loved her still in the days surrounding Sutton’s arrival, but he did not trust her. If my brother and I had not had my father’s auburn hair and freckled skin, his green eyes and his hooked nose, he would have disavowed us as another man’s children, as he had done with my younger sister. She had the misfortune to look like our mother: nut-brown eyes, features delicate and small, and black hair so thick it hung in waves down her back.

She was just a babe when Sutton arrived, and my father hadn’t yet denied her, but in hindsight, it is clear the poisoned thoughts were already in him, twisting him, marking him, making him a man incapable of warmth.

My mother’s death the following year—giving birth to yet another dark-haired babe, a boy who would not live till dawn—completed my father’s transformation. From that night forward, I never saw him smile nor speak a kind word.

The Keep was my father’s. It had been his father’s, and his father’s father’s before him. A large, rectangular building with four small towers, it looked more like a castle or a fortress. But we called it the Keep because it had once been part of a larger complex, filled with granaries and great houses and stables.

They had all crumbled before my father was born, but the ghosts of them remained, leaving their stone footprints on the property. A guard-tower, which had once been part of an acres-long wall, still stood, empty and dust-covered. My brother and I used to explore it before my father hired a nurse after my mother’s death—a nurse who taught me how to stitch and sit quietly and never, ever reveal my innermost thoughts.

The guard-tower had four levels, and a winding staircase that made its way around the interior like braids on a maiden’s nape. The top level had an arching ceiling, and a view that extended for miles on all sides. My brother and I often hid up there from our mother, and she would pretend she could not find us, although our footprints littered the dust, and our giggles echoed through the levels below.

My father gave Sutton the guard-tower as a home. Suddenly my brother and I were forbidden to go within sight distance of the place. We would sneak to the edge of the woods and watch as laborers brought all manner of strange things inside—tables made of shiny material we had never before seen, boxes of foul-smelling roots, and cloth so thin it seemed as if it weren’t woven at all.

Later, the horses would arrive—and cats and dogs—never to be seen again. Other animals as well, things I didn’t recognize, with horns and snouts and short, stubby legs. They would vanish into the first floor of that tower, and sometimes we would hear cries and wails as if the very depths of hell had opened.

But that was after Mother had died. Before, there were no animals, and Sutton would join us at feasts. My mother would tease him—“What miracle have we performed today, Mr. Sutton?”—and he would answer her, telling her of sparkling air or reading stray thoughts. One evening, she made the mistake of laughing at him, and from then on, he would disavow miracles, claiming he did simple magic and nothing more.

My father believed Sutton’s magic was not simple. My father believed Sutton could return our family to its former glory—castles and land and serfs. My father would no longer be a small lord, but a great leader, a warrior-chieftain who might one day unite the other lords, and take on the name of King.

My father never saw that goal—we still have warring lords, arguing tribes, and no unity at all—but he came close.

He came desperately close.

And then I ran away.

***

But I get ahead of myself.

There were years between my rebellion and my mother’s death, years in which my father grew harsher and colder and more ambitious; years in which the strangeness of Sutton’s Tower grew; years in which entire buildings appeared behind it, all of them emitting horrible yowlings and fetid odors, and sometimes, a river of blood.

My father gave my sister to a convent when she was three. Years later, I asked him about her, and he claimed that while she was my sister, she was not his daughter, and he had no obligation to her. I visited the convent once, and no one had heard of her.

She is lost. I do not know why or how.

I asked my brother, but he no longer cared. He became a soldier after my mother’s death. At the age of ten, he wielded a sword twice his size. From then on, I saw my brother only at meals.

He was not allowed to speak to me, and soon he refused to meet my eyes. The closeness we had felt vanished. He became a stranger who drank too much, laughed too hard, and fought recklessly.

When my father started thinking of my brother’s marriage, using my brother’s life to establish alliances, I thought little of it. It is the way among lords—the firstborn must make a good match, whatever the cost.

The women paraded before my brother were often not women at all. Some were mere children. The two years that separated my brother and I seemed like a gulf then. While I still spent time with my nurse learning demure ways to defer to my future husband, my brother had already seen our entire corner of the world.

My father would hold feasts to honor the families who brought their daughters to the Keep seeking an alliance. I attended, but was not allowed to speak unless spoken to, and certainly could not discuss anything with the newcomers.

I did not understand enough of life to fathom my father’s concern with purity. I believed him obsessed with pureness of heart. He did not care about anyone’s heart, having lost his own. He cared only that the woman who married his son was a virgin, and he did not trust doctors and midwives to determine it was so.

So when the young women and their fathers left the feasting hall with my father and Sutton, I thought it a common enough custom. I did not understand the protestations of some lords, the unwillingness of many to even come to our small Keep.

Once I overheard some soldiers speculating about my father’s determination. The soldiers believed that my father investigated the girl’s private parts the way a midwife would, while the girl’s own father looked on.

But the soldiers were as naïve as I was, only in a different way. They did not understand what a midwife later told me—that a girl’s virginity could not always be determined with a look or a touch, that sometimes, a virgin had no proof of it, condemning the innocent girl to charges of promiscuity when, in truth, she had never lain with a man.

The midwife who told me this also confided that she believed this happened to my mother. The wedding night, the midwife said, was a disaster. No blood had spilled on the white sheets, so everyone thought my mother’s maidenhood had not been intact at the time of the wedding.

Yet for her entire marriage, my mother claimed she had never touched a man other than my father.

***

I am exhausted. This forest seems to run forever. The wind echoes in here, whispering through the branches of the mighty oaks that hid the sun. The ground is rugged. I move slower now; my feet so sore that I limp even though I try not to.

I can no longer run.

I look at the tall trees, at the welcoming thick branches with their wide forks, and remember what it was like to be a child, hiding among the leaves.

I think of hiding now. It would be so easy. I would tie what’s left of my shoes to the shreds of my dress, then wedge my bare feet against the rough bark. I would wrap my hands around an easy-to-reach branch, and climb, pulling myself upward until the leaves hide me from the ground below.

My father wouldn’t find me. Neither would Roland or the others.

But the dogs would. I’d seen them tree a cat many times at the edge of the forest, surrounding the trunk, their paws scraping against the bark, baying and howling and barking until someone came.

I used to laugh at the dogs, but I do not now. I think of my father’s cleverness, his intense determination to get whatever he wants, and I shiver.

I continue to stumble forward. I cannot hear the dogs.

I am gaining a fragile hope. Perhaps they have returned to their pen. Perhaps my father has returned to his Keep.

Perhaps this final humiliation will break him.

But most likely, it makes him stronger. My father thrives in adversity.

He made his greatest mistakes when he believed the world was his for the taking.

***

She was tall, like my mother, a woman full grown. A few years older than my brother, she was still unwed. Her fiancé—a man of honor, her father said—had died on the battlefield, and she had mourned him, which was unusual in an alliance that had been arranged from birth.

Her name was Opal, and I thought her the most beautiful creature I had seen. Her hair was so blond it was almost white, and it accented her chiseled cheekbones and sky blue eyes.

She did not smile. She made it clear she had no desire to come to our little Keep and see our pretend kingdom. She did not want to be the lady of this land.

She would, she told my father, eyes blazing in defiance, mourn her lost love for eternity.

“Fine,” my father said to her, “I do not care how you feel, only that, should the alliance be made, you do your part and produce sons.”

She spat at his feet.

Her own father apologized for her. He believed the union advantageous to both families. We had adjoining property, and weaker lords on either side. We could mount an army, he said, and take even more land. He was too old to lead. He would leave that to my father, so long as both families shared in the spoils.

The bargain was made before my brother ever saw his intended.

Not that it mattered. He was smitten from the moment he first looked at that stunning face. She slapped him when he got too close, and after he recovered from his shock, he slapped her in return.

My father laughed.

“Passion,” he said. “It guarantees sons.”

***

But there were no sons. There was no marriage. Opal would not submit to my father’s ministrations. Her own father pleaded, saying there could be no alliance without a guarantee, but she refused.

My father came to me for the first and last time in my life.

“Do you know your mother’s potions?” he asked.

“Some,” I said. “I was too young to learn most of them.”

“A sleeping potion is all I need,” he said.

I could do that.

I felt so pleased to help my father. Finally he had turned to me. Finally he had noticed me.

I would do anything he wanted.

***

I completed the potion in the space of a morning, and tested it on the nurse. She slept deeply, but continued to breathe—always a risk with a sleeping potion. Then I took it to my father.

He thanked me, and said no more.

But I knew he had plans, and I knew they concerned Opal. He had a servant pour the potion in Opal’s wine at that night’s feast. She yawned within minutes, excused herself, and was nearly asleep before she reached the guest quarters.

I excused myself as well, snuck into the guest quarters, and hid across the hall from her room. I wanted to know what my father was up to.

Around midnight, when the feast had dissolved into a drunken party, my father and Sutton came up the servants’ stairs. My father unlocked Opal’s door and went inside. Sutton remained in the hall.

He did not see me, but then Sutton never saw me. His gaze always skimmed past me as if I were a servant, beneath his notice, someone who did not exist.

Still, I did not move. I scarcely breathed.

After a moment, my father exited the room, the sleeping Opal cradled in his arms. He was a strong man, but he had trouble with her weight. Her arms and legs dangled, her hair trailing to the floor. Her feet were bare, her nightdress barely covering her torso.

She slept as soundly as Nurse.

The men tiptoed down the stairs, and I followed as closely as I dared. They wound through the back corridors, past the still hot ovens, toward the yards.

I hated the yards. The stench was abominable—pigs, and cows, and chickens running free. This late, the animals slept, all except one sow who lifted her head from the putrid muck and watched as the men hurried by.

I gave the pigs a wide berth. But the sow put her head down before I passed, and did not watch me at all.

The men went beyond the yards to Sutton’s Tower. My father set Opal on an old stone garden seat and remained with her, while Sutton opened the doors to one of the tower’s new sections. Then Sutton stood aside.

I circled along my old secret path, moving closer so that I could see. I ended up on the edge of the woods, and hid behind an old stump covered with weeds. I made no sound at all. My father did not see me, and Sutton never would.

The fresh scent of evergreen and crushed grass cleared the stench of the yards from my nose. The ground was damp with late-night dew, soaking my slippers within moments. But I didn’t mind; I liked the night and the darkness. I would have enjoyed it more, if it weren’t for the strangeness of my father and Sutton.

They both stared at those open doors. My father leaned against the back of that bench, hands clenched, Opal forgotten behind him. Sutton shifted nervously.

“Perhaps you should move, milord,” he said.

My father nodded, then stepped aside, heading away from me.

At that moment, a light flared inside the new room. The yellow edges of it caught Sutton as if he were a thief. The light came closer and closer, almost blinding in its intensity.

I squinted, and crouched even lower beside the trunk. The light illuminated the dried leaves, the drops of water on the broken blades of grass, the rich brown of the earth near my feet. I wasn’t sure if the light illuminated me as well.

Fortunately, my father did not see me at all. Neither did Sutton. They were staring at a white horse that had emerged from the doors, a white horse with a long horn. From the tip of that horn came the bright light. The horse had blue eyes and a mane the pale colors of the rainbow. The colors shifted with each of the horse’s movements.

Sutton moved to the side, out of the way of the horse. My father placed a hand above his eyes, shielding them.

The horse pranced forward. It paused for a moment. It did not look at the bench.

It looked at me.

I crouched even lower, but I felt the brightness of that light upon me. I raised my head ever so slightly. The horse had not moved, but one of the bright blue eyes held mine.

I shook my head, thinking, No, please, stay away, don’t let them see me.

The horse whinnied, nodded, then turned as if it were guided by unseen hands. It returned to the building, sliding through the doors, and disappeared.

The light slowly faded, but left reflections across my eyes.

“They lied,” my father said. “The unicorn did not go to her. She is not a virgin.”

“It is understandable, given her advanced age—”

“It is not understandable,” my father said. “She has been misrepresented.”

He walked to the doors and pushed them closed. Sutton hadn’t moved.

“Either the virgins are too young,” Sutton said, “or you cannot come to terms with their fathers. Perhaps you should take this one, demand a greater bride price since she is damaged—”

“I will not condemn my son to relive my life!” my father snapped. “I have told you this.”

“Then betroth the boy to a young one. Have him marry her the moment she comes of age.”

“We’ll have to retest her.”

“But the difference is that these fathers know what you’re doing. They won’t allow their daughters to be tainted.”

My father sighed. Then he shook his head, and started back toward the Keep.

“What of the girl?” Sutton asked.

“Leave her,” my father said. “She no longer matters to me.”

***

I waited until Sutton disappeared into his tower, and the lights went out. Then I roused Opal as best I could. She was much bigger than I was, so I could not carry her even if I had the strength.

Instead, I let her lean on me as if she had had too much ale, and helped her back to her room. With luck, she would remember nothing of the trip when she finally awoke.

But I did. The magical horse with its ability to find pure women, my father’s unwillingness to treat Opal with the least civility, and the vehemence in his voice when he spoke of his own life made me leery.

Soon my brother found himself engaged to a child of ten. The wedding, planned three years hence, predated my own by only a few months. He is wed now, though not happily. His young wife is a shrew, and he sees her only to perform his duties or so he says.

I vowed I would not have such a marriage. I vowed I would have warmth in my life, and laughter, like we had when my mother lived.

Although I made these vows, I was not sure I could keep them.

Then my father introduced me to Roland.

***

Roland was a tall man with broad shoulders that tapered into a narrow waist. His eyes crinkled in the corners, and his smile softened his face. He too carried the blood of my mother’s people—the black hair and the dark, dark eyes—but he did not have their ways.

His land lay between my father’s and the sea, most of it forest, all of it valuable. If he allied with my father, he would become part of a clan that extended from the shore to the hills—the most land in all the south.

My father wasn’t yet a king, but he was becoming the largest landowner in the entire country, almost large enough to raise an army equal to that of those who called themselves his betters.

With Roland’s help, my father would finally be in position.

The nuptial negotiations went on before I met Roland, but I did not care. I had always known I would marry to serve my father’s dynastic needs. I had no control over that. I merely hoped I could stomach the union my father chose.

When I met Roland, I was pleased to find him handsome and overjoyed at his tenderness when he took my hand, the softness in his voice when he spoke my name.

There would be affection in this marriage, affection and warmth and laughter. I could build a home as my mother had, and stop thinking about the darkness that was growing around the Keep.

***

By the time I met Roland, I had stopped walking all over my father’s land. I particularly avoided Sutton’s Tower—not because of the strange horse they called a unicorn, but because of the corpses I sometimes found near the wood.

The cat was strange enough. I had discovered it, with its small head and tiny horn, the twisted back and the stunted tail, shortly after my mother’s death. But the dogs, protrusions around their mouths, half formed wings on their backs, disturbed me most. I imagined I saw suffering still in their dead eyes.

The screams and squeals that came from Sutton’s Tower took on a sinister cast for me after that night with Opal, and despite the beauty of the unicorn beast, I realized Sutton was dabbling in something that threatened us all.

For I had no doubt he created these beasts with a particular goal in mind, just as he developed this unicorn to serve my father’s fancy.

I did not think of the virginity then. I thought of it as part of a parcel of a woman’s purity of heart rather than the goal of Sutton’s experiment.

At that point, I also did not think of the quick way in which the unicorn had found me.

I thought, once I met Roland, my life was set.

***

The morning of my wedding—yesterday morning—I stood in my dressing room as the seamstress stitched me into my gown. The wedding dress had a thousand seed pearls for a thousand years of happiness, and a necklace of full-sized pearls sewn into the collar. They matched the pearls along the veil, as did the pearls on the cuffs of my sleeve.

The hairdresser coiled my thick hair around my face, pinched my cheeks, and showed me my reflection in the looking glass. A woman full grown—a beautiful woman, whose skin was as luminous as the pearls, whose softly glowing cheeks reflected the color of her rich auburn hair, whose eyes shown with the light of a thousand-year future—stared at me from the glass.

I did not know that my drunken father had revealed a secret to my bridegroom the night before.

“When you are my son-in-law,” my father whispered, “I will show you how to become rich. I have a beast that approaches only virginal women and shuns those who are not. I used it to ensure the purity of my son’s bride, and I shall lease it out to other fathers who want to do the same.”

That morning—yesterday morning—I was not thinking of the unicorn or my hung-over father. I fantasized about life away from the Keep, about the life I would build with my husband-to-be, about the children we would have—dark-haired girls who looked like my mother, and auburn-haired boys who would remind me of my brother before my father took him away.

I was preparing for happiness, as if it were my due.

***

As I went down the back stairs to the Great Hall where the guests and the priest waited, my brother found me. His left eye was swollen shut, his cheek speckled with blood, his knuckles raw.

“What happened to you?” I asked.

“I’m sorry,” he said, and swept me into his arms.

I was too surprised to struggle. “What’s going on?”

“Roland,” he said with a touch of bitterness, “insists.”

That was enough for me. I would do what Roland said because he was going to be my husband, because I was beginning to believe I loved him, and because I thought he could do no wrong.

Together my brother and I tucked my veil into my bodice, and twined my train around his hand. Then he carried me through the kitchens and into the yards, careful to keep the foul muck from touching me or my dress.

The pigs were awake. They grunted as we passed. The chickens fled, making a half-hearted attempt to fly, and the cows simply looked over their shoulders, surprised that anyone would try to disturb them.

My heart pounded. My mother’s people had a separate wedding ceremony, one that came first, one that guaranteed the union would not be sullied by its brush with the church.

I hoped Roland wanted that, because the other thing—the unicorn—meant he did not trust me, he did not believe me, he needed proof before our first night together.

I had kept myself pure. I had not touched another man. My father would not allow me to be alone with Roland—“You must watch her,” my father had said. “She is tainted by her mother’s blood.”—so in no way could I be impure.

But my word did not count. Women like Opal had twisted my father further, made him believe even less. But I wouldn’t have expected it of Roland.

The moment my brother carried me out of the yards, however, I saw how wrong I was. Roland’s lovely face had a bruised cheek, and the corner of his mouth carried dried blood.

My brother had defended me, and lost. As his price, he had to fetch me to this hideous place so that a creature not created by God could attest to my virginity.

Sutton stood beside the doors, as he had that awful night with Opal. My father stood beside Roland near the fence.

“What caused this?” I asked my brother.

He told me about the drunken conversation, the creature my father had Sutton create to do his bidding, and the allure it held for Roland.

“Roland merely wants to see it work,” my brother said. “This is his best chance.”

Those words should have soothed me.

They did not.

My brother carried me to the stone bench. “It’s just a formality,” he said in an apologetic tone. “You’ll be all right.”

Perhaps I would have been. Perhaps the moment would have passed swiftly, and I would have forgotten Roland’s betrayal, my father’s willingness to show off his toy, and Sutton’s desire to humiliate all women.

But I remembered my first view of the unicorn. It had been an impressive beast from a distance, and I feared it up close. What did it do to determine virginity?

I knew the woman lived after the test—my brother’s wife was proof of this—but was she changed? Had my brother’s wife been a charming child, only to become a shrew after the touch of that ethereal light?

Had she been burned by a spawn of Satan, created by a man who was in league with the devil?

Had the experience so warped her mind that she never trusted again?

I turned on that stone bench, my dress catching on the rough edges, holding me in place.

Sutton opened the doors, and the light flared, as it had before. Only this time, I could see inside the building, see the stable filled with hay, the white horse—the unicorn—and the perfection of its equine face. The blue eyes seemed natural in the light of day, and the pale rainbow hues of the mane seemed a product of the torch that burned atop that strange horn.

The unicorn pranced toward me, its head lifted, its tail up, as if it were coming toward someone it knew and loved.

And, God help me, I raised my hands to my mouth, as terrified—more terrified—than I had been that night in the woods. I could scarcely breathe.

Please, no, I thought. Don’t come near me. Don’t hurt me. Please.

The unicorn stopped in confusion. It looked over its shoulder at Sutton, then at my father, and finally at me.

A tear traced its way down my cheek. Please . . .

The unicorn nodded, tilted its head, and I felt a warmth, an understanding. Perhaps—

The word was not mine. I squeezed my eyes tightly shut and cowered, preparing for the touch of that magic light. Instead, I heard a whinny and my father’s cursing, and then Roland—Roland!—screaming, “You liar. You barbaric liar! You promised me a virgin bride, a good girl, and what do we have? A whore. A whore in virgin white.”

I opened my eyes.

My father was staring at me as if he had never seen me before. My brother started walking toward the yards, his back to me, as if I no longer mattered.

Roland grabbed my veil and yanked it off my head. His hand held my hair, pulling it so hard my scalp ached.

He raised his hand to cuff me, and I came alive. I punched him in the stomach, then kicked him in the knee, making his leg crumble. I shoved him away, tugged my hair from his grasp, and ran toward the forest.

“Stop her!” Roland shouted.

“Why would you want to do that?” Sutton asked. “She’s not what you want.”

“I never said I wouldn’t marry her,” Roland snapped. “She just has to be punished for her betrayal, so that it would never happen again.”

My betrayal. Mine? What about his? Who had that loving man been, that hero of my dreams, the husband who would take me from all of this?

A figment of my imagination?

A lie?

I had done nothing, and he had accused me of betrayal.

I kept running, hoping my father would defend me. It was a false test, he would say, created to ferret other men’s lies.

But he said nothing. Finally, Sutton shouted, “Milord, we need her. She must not get away!”

“She is her mother,” my father said, his voice half-hidden beneath my ragged breathing, my panic. “I should have known.”

And then I was in the trees, my dress catching on bark. I ripped the bottom half away and kept running, tears flowing down my cheeks.

“We’ll never catch her now,” Roland shouted. “Get the dogs!”

I hit a clearing and slipped on a patch of dirt. My feet went out from under me, and I landed on my back. The dirt moved. I was sliding downward. I hit a rock at the bottom, tumbled forward, and struggled to catch my breath.

Behind me I heard nothing.

I had a few moments. If they were going to get the dogs, I had only a few moments. But I had to outthink them. If I could stay away from the dogs, I could run through the woods and maybe make it to the shore, and my mother’s people.

Or if I came out near a village, I could sell the pearls, and get enough gold to buy food, new clothing, maybe even a horse. I could live on my own somewhere else, where there was no magic, no family, and no betrayals.

For the first time, I thanked my father for all his fox-hunting conversations at the various feasts. I knew how foxes somehow escaped the dogs. I had tricks that I could at least try.

I ripped my dress, strung some of the shredded pieces down a side path, then backtraced my steps. I held the dress up so that it wouldn’t catch any more and headed forward, crossing a small stream so that the dogs would lose my scent.

Then I hurried deep into the forest, always moving, never stopping, forever listening, for barking, baying, and the sounds of the hunt.

***

I am near collapse. A few berries, little water, no rest. I doubt I can keep going much longer.

Yet the forest continues forever. Perhaps there is no end to it. Perhaps I’ll die in here, alone, unmourned, spoken of as the humiliation of my family if I’m ever spoken of again.

I keep thinking I hear dogs, but they’re not barking. They crash through the woods, occasionally huff as if something pricks them. I never think of dogs as silent creatures, hunting with determination.

Maybe my father didn’t take Roland’s suggestion. Maybe I’m fleeing for no reason.

Maybe no one is searching for me at all.

That thought makes me stop. I bend over, trying to catch my breath. Little spots dance in front of my eyes. I stand, brace a hand against a tree trunk, and blink, hoping I don’t pass out.

The crashing, ever so faint. I have heard it since yesterday.

The dogs bay when they tree a fox. They bark when they get close, letting their masters know that the fox is within sight.

This part of the forest is too dense for horseback riding. My father, Roland, my brother, they would have to come on foot.

I cannot hear them, either.

The idea that they would not come hurts more than the idea that they’re chasing me. It merely confirms that I have no value. That I am nothing to my father, my brother, and a man I once thought my beloved.

I am nothing.

The huffing gets even closer, and I see something white through the trees. White, yet filled with the colors of the rainbow.

My breath catches. I blink, wondering if I am so exhausted that I’m seeing visions.

Then the unicorn steps into the patch of trees. Its flank is scratched, its mane filled with leaves and burrs. It stares at me, the blue eyes filled with knowledge.

Stop running. Please.

The voice in my head is not my own. I lean against the tree, using it to hold me up.

I am so sorry. I didn’t know turning away would make them abandon you.

“How can you speak?” I whisper.

I don’t speak. I have thoughts. I can share them with women like you. It’s part of the magic.

The unicorn bows its head. The horn—which is not flaring with light—nearly hits a tree branch.

I didn’t want them to hurt you. I thought if they let you go, you would be safe. I didn’t realize until too late you belonged to them.

“Not any more.” My voice is weak, even though I’m no longer trying to whisper.

It’s better this way. You have no idea how cruel they are.

Because I closed my eyes. I did not want to see. They were part of my home.

But I wanted to get away. I wanted a perfect, happy life with Roland.

“How did you escape?”

They didn’t close the door. I followed you. They didn’t even realize I had left.

But they would. My father guards his possessions, at least the ones he values. The ones he doesn’t value get lost.

Like my sister.

“They’ll come for you.”

Yes.

Unlike me. They won’t come for me.

But they won’t catch me if I don’t want them to. We can stay together.

“Why would I stay with you?” I ask, then wince at the cruelty in my speech. Cruelty that hides some truth. Why would I stay with this thing? I don’t even know what it is.

I don’t know what I am either. Except that I do not fit there. Neither do you. We are of a kind, and we are alone. Let us stay together. I will help you travel, and you will help me learn. And somehow, we will stay away from them.

A shiver runs through me. “You read my thoughts.”

When they’re powerful enough.

“Only mine?”

Yes.

The unicorn raises its head. Our gazes meet. Its blue eyes are gentle.

It has never ever been cruel to me. In fact, it is the only one in my life who has ever heard me or done as I asked.

I step forward, hand extended. “May I touch you?”

Yes.

I do. The hair on its nose is rough beneath my fingers, like horsehair. The horn does not flare with light, but looks very solid.

The unicorn watches me, its body trembling.

Except for our breathing, the woods are silent. Not even a bird chirps. And no dogs bark, no humans crash through the bushes.

No one knows where we are.

“Have you ever seen the sea?” I ask.

I do not even know what a sea is. It continues to watch me, its mane shifting from red to pink to white to blue.

“It’s where my mother’s people live.” Where everyone laughs with joy, and doesn’t judge, where they marry not in front of a priest, but by clasping hands and vowing eternal love.

I believe in love, it says.

“So do I.” I smile. That’s enough, at least for a beginning.

I put my hand on its flank.

Together, the unicorn and I walk through the forest, away from my father’s land, across Roland’s, all the way to the sea.

Hello Human. I hope you enjoyed this magnificent story. Please support SciFiwise.com and our authors by:

- Rate and React to this story. Feedback helps me select future stories.

- Share links to our stories and tell your human friends how charming I am.

- Click on our affiliate links and buy books written by our talented authors.

- Follow me on twitter: @WiseBot and also follow @SciFiwise.

Thank you!

WiseBot

VISIT AUTHOR:

VISIT AUTHOR:  SHOP AUTHOR:

SHOP AUTHOR:

TIP AUTHOR:

TIP AUTHOR: