1.

the execution

The nameless man who had killed and been caught, judged and sentenced and jailed to await his own death watched as the authorities prepared to execute his surrogate.

The murderer occupied one place in a bank of seats filled by other invited witnesses to the State’s administration of mortal justice. He had not been introduced to any of the other witnesses when the guards had coldly and somewhat roughly conducted him to his seat, and no one had since offered a name or hand to the man.

Understandably so. Quite understandably, as things stood now at this crucial cusp, this instant when the exchange of lives, the legal and spiritual transaction, was still incomplete.

But once the execution was over, he had been promised that this would change.

This promise he still found hard to believe or trust.

Despite all he had been through to earn it.

With the little bit of his attention and vision not devoted to the spectacle slowly unfolding before him–a spectacle in which, save for the most tenuous chain of circumstances, he himself would have been the star–the nameless man tried to assign roles to the others around him.

The Warden, of course, he recognized, as well as the dozen members of the Renormalization Board. Several people tapping busily on laptop keyboards he deemed journalists. A man and a woman who shared an officious, self-important air he instinctively knew for politicians. With a small shudder, he pegged a trio comprised of two expensively suited men and an equally dapper woman as doctors here to observe him. An inexpungable air of the examining–the operating–room still clung to their costly clothes.

But the bulk of the watchers, he knew, were the surrogate’s family.

Weeping with quiet dignity, holding onto each other, they disconcerted the nameless man deeply. He could not watch them long, couldn’t even count how many there were, or of what sexes or ages.

Yet be knew that soon he would have to match the living, tear-stained faces to the photographs he had studied for so many months.

Soon his intimacy with these strangers would extend far beyond mere faces and names.

There were none of the nameless man’s relatives present. Even if the distant kin–distant geographically and emotionally–who still claimed him had wanted to attend, they would not have been allowed to.

After all, what would have been the point? The man he had been was soon to be dead.

Now, across the room, on the far side of a wide sealed glass window, a shifting of focus among the workers there riveted the attention of the nameless man and all the others.

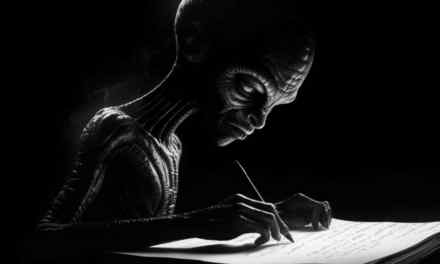

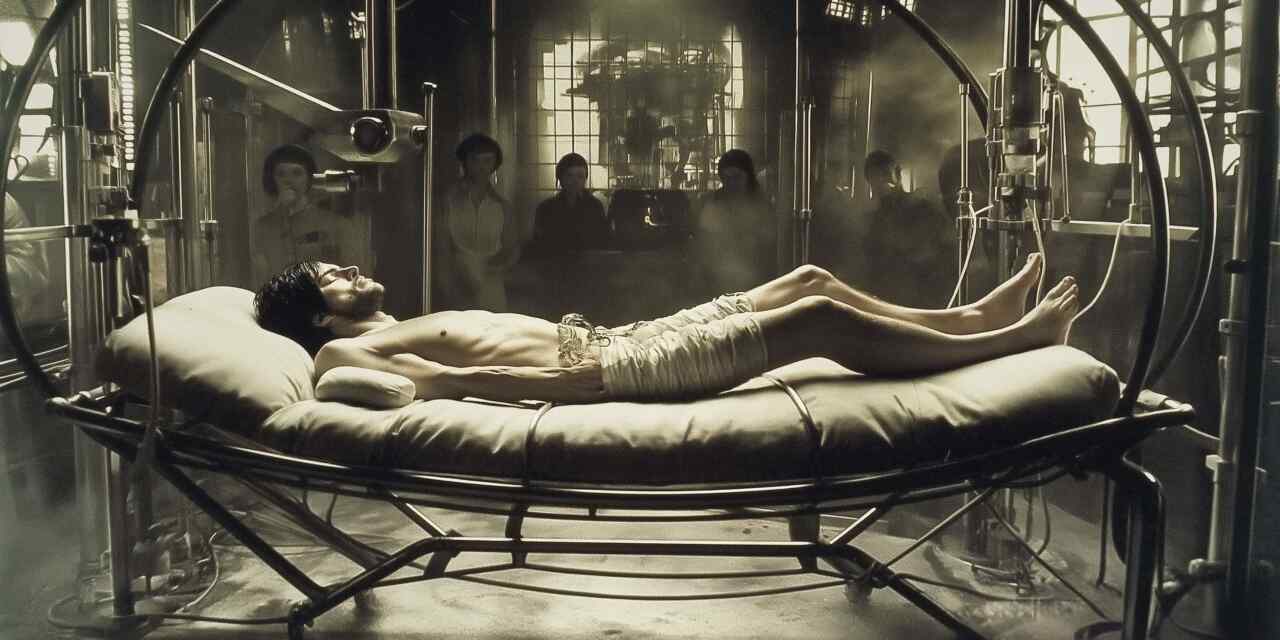

The technicians had finished checking out the mechanisms of death, the drips and needles and biomonitors and video cameras. Some signal must have been passed to those outside the immediate view of the watchers. For now the surrogate was being wheeled in.

The man was cradled by molded foam supports on a gurney. Thin and wasted, he was nonetheless conscious and alert, thanks to various painkillers and palliative drugs. After he was maneuvered into the center of the web of death-apparatus and the wheels of his gurney were locked, the surrogate managed to raise himself slightly up on one arm to gaze out at the audience, smile wanly and wave weakly with his free hand.

In the brief instant before the surrogate flopped back onto his pillow, the nameless man received the image of the dying man’s face into his brain in an instant, imperishable imprinting.

When the cushions and pillows had been readjusted around the surrogate, a triggering device, its cord leading in an arc to the death-apparatus, was placed in his right hand.

Following the surrogate had come a priest of the Gaian Pragmatic Pandenominationalists. Arranging his green stole nervously, the priest faced the audience on the far side of the glass. A technician flicked a switch, and sounds from the far side of the barrier-beeps and shoe-scuffings, coughs and whispers-issued forth from a speaker on the nameless man’s side.

Then the priest began to speak.

“We are gathered here today to bear witness to the utmost sacrifice that any individual can make to the society of which he has since birth formed a grateful part. Far greater than such paltry donations as those of blood or organs is what the man by my side will render today. He will give up his very name and identity so that another may live and serve in his place. Doomed to perish of his own incurable affliction, having opted for a voluntary death, this man takes on–legally and ethically–the sins of one of his erring brothers, thus granting the guilty one a second chance. At the same time, the demands of society for justice and retribution are met. A crime–the most heinous crime, that of murder–has been committed, and today it is balanced by the death of its perpetrator. Our laws are not flouted, the guilty do not escape, and the scales of justice swing evenly.

“I will not eulogize the man by my side at any greater length. Last night at the hospital I attended the official farewell ceremonies hosted by his loving family and friends, and we all spoke of him at length, by his bedside, to his smiling face, It was a fine occasion, with joyous memories leavening the tears. He knows with what love and reverence and gratitude he is esteemed, and all the goodbyes and final words have been said.”

The wordless sobs of the surrogate’s family swelled, and the nameless man winced. He rubbed a sweaty hand across the regrowing stubble on his scalp, imagined he could feel the crown-encircling scar, although in truth it was already nearly invisible.

“Now,” the priest resumed, “the man by my side assumes a new identity, taking on the bloody garments and sins of the murderer known as–” Here the priest uttered the name which had once belonged to the seated man on the far side of the glass. Curiously, the once-familiar syllables rang hollow to him, drained already of all meaning, distant as something from a history book.

“It is a light load, however,” continued the priest, “and a burden instantly extinguished in the very taking of it. Christ Himself could do no more. Now, let us pray.”

The sound was shut off. The soundlessly murmuring priest bent over the supine man, and relative silence descended on the audience.

The nameless man did something he thought–he hoped–was praying.

Now the execution room emptied of everyone but the surrogate, recumbent on his trolley, gaunt face obscured. He could be seen with a flick of his thumb to trip the trigger, murderer in truth at the final moment, if only of himself.

The red power-on LED’s of the official recording cameras glared down on the scene. After an interminable ten minutes during which the calculated poisons circulated through the surrogate’s veins and his breathing slowly ceased, the prison doctor entered the sealed room, performed his exam, and looked up. Although he had forgotten to activate the speaker, all could plainly read his lips shaping the words, “He’s dead.”

The Warden stood and approached the nameless man, who flinched. That dour official essayed a tentative smile is cameras flashed, and extended his hand toward the murderer. The murderer took it reflexively.

“Mister Glen Swan, I thank you for your participation in this event. We will detain you only for a few last formalities, signatures and such. Then you will be free to leave. But now allow me to introduce you to your new family.”

2.

the murder

The air underground was stale and hot, redolent of train-grease, electricity, sweat, fried food, piss-wet newspapers. The platform was more crowded than the murderer-to-be had anticipated. He had not known of a new play in the neighborhood, whose audience now spilled out and down into the subway. Such events were outside his calculus, and he would have still been baffled, had it not been or the overheard chance comments of the crowd.

The man felt uneasy. But he finally resolved to carry out his plans.

Necessity–and something resembling pride in his illicit trade–compelled him.

His roving eyes finally settled on a victim: a middle-aged woman in a fur coat, seemingly unaccompanied, clutching a strapless evening purse. He began to move toward her in a seemingly aimless yet underlyingly purposeful path.

The rumble and screech of an approaching train emerged from some distance down the tunnel. People surged closer to the edge of the platform in anticipation.

The man came up behind his apparently unaware victim, within reach of the shiny black purse clutched against her side.

Then it was in his hands. He tugged and pivoted.

The purse did not come. A thin hidden gold chain was looped around the woman’s wrist.

He yanked, she screamed and flailed. He grabbed her wrist to immobilize it so that he could get the bag off. She jerked backward at the touch, the chain parted, his grip slipped, and the woman tumbled out of sight, onto the tracks.

The man turned to flee, but was brought crashingly down within a few yards by two bystanders, large men who began to pound him, smash him with their fists to stop his instinctive resistance.

And because his battered face was pressed into the filthy concrete at the moment he became a murderer, he did not see the train actually kill the woman.

But he heard and would always remember the noise of its useless brakes and the shouts of the witnesses and the victim’s final cut-off high piercing scream.

“We think we have some chance of success with you,” said the head of the Renormalization Board, as he looked up from closing a window on his lap-top, a window full of information on the nameless man. “But everything depends on your attitude. You will have to work at this, perhaps harder than you’ve ever worked at anything before. Your reintegration into society will not be without obstacles or sacrifices. Do you think you can commit to this course of action? Honestly, without reservations?”

Sitting across a wide polished table from the Board, the murderer tried to hide his astonishment and suspicion, keep it from altering the silent stony lines of his face. After six months on Death Row, his appeals up to and including the highest court exhausted in the streamlined new postmillennial system, with imminent and certain death staring him hourly in the face, he would agree to anything. Surely they knew that. Anything they could offer, even a life sentence, would be better than the alternative. And as he so far dimly understood the choice before him, it was infinitely more attractive than spending the rest of his natural days behind bars.

But after he said the assuring words these new judges wanted to hear and the Board began to explain exactly what lay in store for him, he began to have his first small trepidations.

“The first thing we are going to do is perhaps the most dramatic, yet surprisingly, not the most crucial. We are going to lift the top of your skull off and insert a little helper.

“Your cortex will be overlaid with a living mass of paraneurons known as an Ethical Glial Assistant, which will also have dendritic connections to various subsystems in your brain. This ECA has no independent capacities of its own, and assuredly no personality, no emotional or intellectual traits. You may think of it simply as a living switch. It has one function, and one function only. It will monitor aggressive impulses in your brain. Upon reaching a certain threshold–a threshold of whose approach you will be amply warned by various unpleasant bodily sensations–it will simply shut you down. You will go unconscious, and remain so for a period varying from half an hour to a day, depending on the severity of the attack.

“At this point, we would like to stress all the things the EGA will not do. It will not prevent you from physically defending yourself under most circumstances, although some incidents of this sort might very well pass into an aggressive stage and trigger the switch. It will not hinder your free will in any manner. You are always at liberty to attempt aggression; it is just that you must be willing to face the consequences.” The Boardmember’s voice became very dry. “We can report that most people’s automobile driving styles change radically. In any case, we have no interest in turning you into some kind of clockwork human. You would be of little use to society and the planet that way. The SCA is by no means foolproof. It will certainly not thwart a coolly premeditated murder for profit. It works only on spontaneous limbic impulses of rage and attack.

“But we do not feel, based on your case history, that you are at risk of the more calculated life-threatening behavior. The antidote we are giving you is precisely tailored for the type of person you are. Or once showed yourself to be. With the help of the EGA, you will be rendered relatively safe to mingle with your fellow humans. As safe, in fact, as any of them generally are themselves. Do you understand all this so far?”

The murderer could not focus on anything other than the queasy image of his head being opened and a living mass of jelly dropped in. But then the picture of his cell and its proximity to the execution chambers returned.

“Yes,” he said.

“Good, good. Now, we are not going to rely entirely on the ECA. It is, in its way, a last-ditch defense. You are going to undergo an intensive course of remedial psychosocial pragmatics. At the end of that time, if you have exhibited cooperation and commitment, you will be certified a fully functional member of society.”

The prisoner could contain the question no longer. “And then, I’ll be released? Free?”

The Boardmember smiled wryly. “In a manner of speaking, yes. Completely free. Yet with duties. The duties any of us here might have, to our society and the globe. You’ll receive a brochure that explains it all. It’s quite simple, really.”

The head of the Renormalization Board now opened up a scheduling window on his computer. “Let me see . . . Assuming you can complete the standard six-month course, and that Mr. Swan survives till then in order to serve as your surrogate–Yes, I think that we can confidently schedule your execution for the fifteenth of May. How does that sound to you?”

“Fine. Uh, fine.”

4.

the brochure

For the hundredth time, returned to his cell after a day’s demanding, confusing, stimulating classes, the prisoner read the brochure.

–key concept is that of commensurate restitution, combined with the notion of stabilizing broken domestic environments by insertion of the missing human element.

Previous attempts at reintroducing ex-inmates to society have often failed, resulting in high rates of recidivism, precisely because there was no supporting matrix cushion the inmate’s transition. Uncaring systems comprised of parole officers and halfway houses could not match the advantages offered by a steady job, caring coworkers and a supportive family eager to make the inmate’s transition a success.

Obviously such a set of supports is almost impossible to manufacture from scratch. Yet if an ex-prisoner could be simply plugged into the gap in an existing structure, an instant framework would be available for his or her reentry into society.

The murderer skipped ahead to the part that most concerned him.

Prisoners awaiting capital punishment offer a particularly vivid and clear-cut instance of the substitution-restitution philosophy. Basically, as they await their fate, they are non-persons. By their actions, they have forfeited their identities and futures, their niche in the planetary web. In their old roles, they are of no value to society and the planet except as examples of our intolerance for certain behaviors.

Meanwhile, another segment of society ironically mirrors the role of the condemned prisoner. The terminally ill among us have been condemned by nature to untimely deaths. Guilty of nothing except sharing our common mortal heritage, they yet face a sentence of premature death. In most cases, the doomed man or woman is tightly bound into an extended family and set of friends, an integral part of many networks, perhaps the sole breadwinner for several mouths.

How fitting, then, that the terminally ill patient intent on using his right to voluntary euthanasia (see the Supreme Court decision in the case of Kevorkian vs State of Michigan, 2002), intent also on providing security for his loved ones in his or her absence, should gain a kind of extended life through an exchange with the prisoner who has abandoned his.

The prisoner turned several more pages.

Every attempt is made to match the prisoner and surrogate closely on the basis of dozens of parameters. The environment in which the ex-inmate is placed should therefore prove to be as comfortable and supportive for him as possible. Likewise, his or her new family should have a headstart on the adjustment process.

Simply put, prisoner and surrogate undergo a complete exchange of identities. For the surrogate the road after the exchange is short. For the prisoner, it extends for the rest of his lifetime. There is no return to his old identity or life permitted.

The prisoner assumes the complete moral and legal responsibilities, duties, attachments, and perquisites–the complete history, in short–of his new identity. All State and corporate databases are altered to reflect the change (ie, fingerprints, photos, signatures, viral measurements, medical records, etc. of the dying surrogate are updated to reflect the physical parameters of the ex- prisoner). After taking this action, the State ceases to monitor the ex-prisoner in any special way. He becomes a normal citizen again.

How does restitution occur? Simply by the ex-inmate’s willing continuation of the existence of the surrogate, as father or mother, son or daughter, breadwinner or homemaker.

This is not to deny that post-transition changes will almost certainly occur. Minor lifestyle alterations are inevitable; major ones are likely. Any option open to the original possessor of the identity is open to his replacement. Just as the surrogate could have decided to initiate a divorce, adopt a child, switch jobs or relocate his residence, so may the ex-prisoner decide. Yet the important thing is that all such decisions are not undertaken in a vacuum. Domestic, financial and other constraints faced by the original remain, and must be negotiated. Yet the history of this program reveals a surprising stability of these newly reconfigured families.

And of course any illegality perpetrated by the new possessor of the identity is fully punishable, in accordance with relevant laws, bringing down relevant punishments. Parents who abandon their new family, for instance, are subject to arrest and the standard penalties for non-support. Spousal abuse and marital rape merit the strictest punishments…

The prisoner set the booklet down on his knee for a moment, lost in thought. When he picked it up once more, he opened it to the final page.

Perhaps some will say that the State is acting arbitrarily or capriciously in mandating such substitutions. Humans are not interchangeable, some will argue. Emotions and feelings are neglected or trampled. Every individual is unique, one cannot be exchanged for another by government fiat. Utilitarianism has limits, they say. The State is coming perilously close to playing God.

Yet what are the alternatives? To let a perfectly useable individual, often in the prime of his or her life, be put to death as in premillennial days, while for lack of one of its prematurely taken members a bereaved family falls to pieces, becoming a burden on State welfare rolls? This is not acceptable, either to the State or to its citizens. And historically, many precedents for such behavior exist.

Dissenters to this policy might be advised to consider it in terms of an arranged marriage.

5.

the new home

The car pulled into the short oil-spotted driveway, a length of buckling asphalt barely longer than the shabby old hydrogen-powered compact itself. For a moment, the engine continued to idle. No one emerged. Then the motor was cut, and Mr. Glen Swan opened the passenger’s door and stepped out.

The postcard-sized yard was ankle-high with the vigorous weeds of late spring. A cement walkway led from the driveway to the scuffed door of a small house that was plainly the architectural clone of its many close-pressing neighbors. The yellow paint on the bungalow was flaking. A plastic trike lay oh its side, half on the walk, half on the lawn, one wheel still uselessly spinning in the air.

Swan studied the scene, It was nicer than anyplace he had ever lived.

And much, much nicer than the prison.

Movement by his left side startled him from his reverie. He hadn’t even heard the car’s driverside door open and close.

Without taking his gaze from the house, Swan said the first thing that came to his mind. “Uh, it’s nice.”

A woman’s voice responded, if not flatly, then with a measure of reserve. “It’s home.”

Swan could not immediately think of what else to say. So, still regarding the house, he repeated something he had said earlier, said more than once.

“I’m sorry you had to drive. It’s just that I never learned how.”

The woman’s voice remained level, neither frustrated nor sympathetic, though her words partook of some small traces of both emotions. “You apologized enough already. Don’t worry. You’ll learn how soon enough. Meanwhile you can ride the bus. The stop is just five blocks away.”

There was silence between them. Then the woman said, “Do you want to go in?”

“Yeah. Sure. Thanks.”

The woman sighed. “You don’t have to thank me. It’s your house too.”

6.

the son

The front parlor was decorated with a wooden plaque bearing a Pragmatist inspirational motto (REGARD ONLY THE OUTPUT OF THE BLACK BOX), a framed print of a nature scene, a dusty artificial bouquet. The couch and chairs had seen much wear. A low table held several quietly murmuring magazines, the cheap batteries powering their advertisements running low with age.

There were no pictures displayed of the man who had died in Swan’s place. But Swan had no trouble calling up his face.

There was another woman inside the house. She was trim, on the petite side, brown hair cut short, and wore a pair of green stretchpants topped by a white sweater in the new pixel-stitch style. Her sweater depicted a realistic cloud-wrapped Earth.

“Hi,” the woman said, attempting a small smile. “Welcome home.”

Because of his studies, Swan recognized the woman as his sister-in-law, Sally.

“Hi, uh, Sally.” He extended his hand, and she shook it. Swan liked the fact that people would shake his hand now. He was starting to believe a little more in all this, in the whole scenario of exculpation, although every other minute he still expected the carpet of his freedom to be pulled from beneath his feet, sending him tumbling back into his cell.

“Will’s in his bedroom,” said Sally a little nervously, addressing mostly the other woman. “He was very good all morning. But when he saw the car…”

Emboldened by the ease of the transition so far, of his seeming acceptance by the two women, made slightly giddy by the very air of freedom on this, the late afternoon of the day of his execution, recalling several of the mottoes of his pragmatics classes that counseled forthrightness and confidence, Swan said, “I’ll go see him.”

The layout of the house had been among his study materials. Swan strode confidently to the boy’s bedroom door. He knocked and called out, “‘Will, it’s me, your father.”

Behind him the two women were quiet. Through the door came no words, just small sounds of a small body moving.

Swan raised his hand to knock again, but before he could the door opened.

Will was four, but tall for his age. From photos Swan knew his face very well. But he could not see it now.

Will wore the all-enveloping rubber mask of sonic kind of reptilian alien, possibly from Star Wars VI.

“You’re Glen now,” the boy said, his voice muffled.

Swan squatted, putting his face on a level with tile goofy mask. “That’s right. And you’re Will.”

“No,” said the boy firmly. “Not anymore.”

7.

the wife

Their first supper together as a family of three was a largely silent affair, save for a few neutral questions and comments, perfunctory requests and assents. Swan tasted nothing vividly, except perhaps the single beer he permitted himself. Never much of a drinker, he was somewhat startled to find how much he had missed the flavor of the drink, the feelings of sociability it conjured up, while in prison.

Will had been convinced to discard his mask for supper. Swan smiled frequently at him. The handsome young boy–Swan fancied lie could spot some affinities between the young face and the one he himself saw in the mirror each morning–returned the smiles with a look not belligerent, but distant as the stars.

Much of the meal Swan spent covertly studying his wife. Emma Swan both cooperated with and slightly frustrated this inspection by eating with her head mostly lowered over her plate.

Swan’s wife resembled her sister Sally in height and build. But her face, thought Swan, was prettier and her longer, lighter hair suited her. Although some of her movements were nervously awkward, she exhibited an overall easy grace.

Glen Swan had been a lucky man, he thought.

But I’m Glen Swan now.

So does that mean that I share his luck?

Shortly after cleanup, which Swan volunteered to handle, it was time for Will to go to bed.

Wearing one piece pajamas, Will emerged from his bedroom. A different mask hid his features, this one of a Disney character, some kind of animal prince or hero, Swan guessed.

Emma herded the boy up to where Swan sat.

“Say goodnight to your father.”

Will had adopted a chirpy new voice to go with the mask. “Good-eek-eek-night.”

Mother and son went into the bedroom. Swan did not follow. He could hear Emma reading a book aloud. Then the lights were extinguished, and she came out, closing the door softly behind herself.

Swan’s wife took a scat on the couch. She looked at Swan directly for the first time that day, as if perhaps the ritual in the bedroom had given her strength or firmed up a decision.

“Do you want to watch some TV?”

“Sure.”

Watching TV, Swan knew, meant they didn’t have to talk.

Right now, this first night, that was just as well.

But he knew they couldn’t watch TV for the rest of their lives.

Hours passed. Once, Emma laughed at a sitcom. Swan enjoyed hearing her laughter.

Shortly before midnight, Emma clicked off the television, She stood and stretched.

“You have to be at work by eight. Me too.”

“Right, right,” Swan agreed readily. “And Will–?”

“I’ll drop him off at the daycare on the way to the Wal-Mart.”

The couch seemed to be a sofabed. Swan looked around for signs of bedding. But Emma’s next words informed him differently.

“When Glen–When the sickness hit us, I got twin beds in. It made things easier for everyone. Anyway, I’ve thought about this a lot. We can’t act like complete strangers, hiding things from each other. We have to share this small house. Bathroom, whatever. Getting dressed. So we have to be at least as close as roommates. Like in a dorm. Anything else–I don’t know yet. It’s too soon. Is that okay with you? Am I making any sense?”

Swan considered how best to answer. “Roommates. That’s fine.”

Emma slumped in relief. “Okay. That’s settled. Good. Let’s get to sleep. I’m completely wiped out.”

Lying in the dark, Swan listened to Emma’s breathing, only a few feet away. The rhythm of her breath gradually smoothed out and softened, till he knew she was asleep.

He had expected her to sob. But after some thought, he realized that her tears must have been drained long ago, the very last ones shed in the death chamber.

And certainly not for him.

the job

His boss was a big man with the startling, abnormally delicate hands of a woman. His name was Tony Eubanks. Tony was the supervisor for a crew of ten men, split between five trucks. Normally Tony stayed put in the office, dispatching his fleet, scheduling assignments, handling paperwork. But for the duration of Swan’s training period he would go on the road with Swan, functioning as Swan’s partner and teacher.

Swan knew that this was special attention, for his special case. So, of course, did everyone else. The people in charge of his future, while not actively monitoring him, had nonetheless seeded his path with mentors.

Swan tried not to think of Tony as a jailer or warden. Luckily, as Swan soon discovered to his relief, Tony’s attitude made it easy to regard him as simply a more knowledgeable co-worker, perhaps even a friend.

The attitudes of the other linemen, however, were less easy to pin down.

For the first few weeks, busy learning and doing, Swan was able simply to ignore them.

He and Tony were stringing cable. Lots of new cable. It was some kind of special new cable meant to treble the bandwidth of the net. Swan never got a really firm grip on the physics behind the wire. But then again, he didn’t need to. All he needed to master was the practical stuff. The tools, the junction boxes, the repeaters, the debugging tricks, the protocols. He concentrated on these with his full attention, and was proud to realize that he could learn such things, mastering them fairly easily.

The physical side of his job was enjoyable too. Up and down poles, into ditches and tunnels, popping manhole covers, manhandling big reels, driving the truck. All of these actions appealed to him.

Tony, however, was not so enthralled. In the truck, with one of their endless cups of coffee in hand, he would frequently say, in a kindly way, “Jesus, kid, I’m getting too old for this kind of workout. I can hardly get to sleep at night for the fucking aches and pains. I’m glad you’re picking up on things quick. I never thought I’d say it, but I can’t wait to see my fucking desk again.”

The hard work had the opposite effect on Swan’s sleep patterns. Each night, after the repeated rituals of meal, television, and brief, safely shallow conversation with. Emma, he dropped off into dreamless slumbers.

Part of the job involved dealing with customers. It was the hardest part for Swan to adapt to. Entering offices and homes, he encountered a spectrum of people utterly foreign to him. At first, he would stammer and perform clumsily. Forms that had to be filled out confused him, and Tony would have to intervene.

But after a time, he found himself warming to even this aspect of his job. One day he was surprised to find himself actually looking forward to dealing with a complex installation that required him to speak frequently with a pretty woman manager in charge of the project.

Tony approved of Swan’s new interpersonal skills. One day when they had just left the job site, he said, “You handled her nice, kid. And she really had a bug up her ass about those delays. Couldn’t have done it any better myself. In fact, you’d better watch it or the suits are gonna catch wind of how slick you’ve gotten and the next thing you know you’ll be locked up behind a desk all day like me.

Swan beamed. He felt close to Tony. Close enough to ask him the next day a long-held question about his hands.

Tony held up his small hands without embarrassment. “These mitts? Replacements. Lost my original ones in an accident on my old job. Got a little too careless around an industrial robot. I was one of the first patients where the graft took. Back then, they had to do it within the first twenty-fours hours, the donor had to match nine ways from Sunday, a lot of shit they don’t have to worry about nowadays, Anyhow, everything came together so’s I had to take these or nothing.” Tony was quiet a moment. “She died in a car crash while I was lying in the hospital. Head crushed, but hands fine, I still see her parents now and then.”

Swan was silent, as was Tony. Then the older man shrugged. “No big deal, I guess. They can replace anything nowadays.”

9.

the merger

It happened over the course of the next eight months, by a process Swan could neither chart nor predict.

He became, on a level sufficiently deep to pass mostly out of conscious scrutiny, his new self.

In his own eyes and his adopted family’s.

What caused the merger was nothing other than simple daily repetition, the hourly unrelenting enactment of a good lie engineered by the State. The continuous make-believe, bolstered by a mostly willing shared suspension of disbelief, eventually solidified into reality. Under the sustained subtle assault of the mundane and the quotidian, the blandishments of the hundred bland rituals and the shared demands of a thousand niggling decisions, reality conformed to imagination.

What greased the way was a desperate willingness to succeed on the part of Swan and Emma, a loneliness and void, shaped differently in each, yet reciprocal, that eagerly accepted any wholesome psychic fill.

The path to the merger was made of uncountable little things.

Swan had very few clothes to call his own. It was only natural for him to use those of the man who had preceded him. They fit remarkably well, a fact the Renormalization Board had doubtlessly reckoned with.

Will enjoyed making models out of the new memory clay for children. Swan discovered a facility for shaping that allowed him and the boy to spend some quiet hours together.

His sister-in-law Sally, having overcome the hurdle of meeting him early on, was a frequent visitor. With her husband, Al, and their daughters, Melinda and Michelle, the two families went places the movies, picnics, amusement parks, the beach. Apparently, reports back to the rest of Swan’s new relatives were encouraging enough that the massive multifamily get-together held each Labor Day did not have to be cancelled this sad, strange year.

At the outdoor gathering Swan’s head spun from greeting so many familiar strangers, from heat and sun and the usual overindulgences of food and drink. But by day’s end, he had earned high accolades from Emma.

“They liked you. And you fit right in.”

Emma.

She taught him to drive. They shopped for groceries together, went to conferences at Will’s daycare together, watched endless hours of television side by side on the couch, apart at first, then holding hands, then her in his arms.

But each night, even after a year, Swan slept in his bed, and she in hers.

10.

the torment

Swan had been paired with a guy named Charlie Sproul for several months. Charlie was fairly silent and self-contained, not very friendly. It wasn’t like working with Tony. Swan tried to make the best of it though.

One afternoon in the locker room, Swan was surprised when Charlie and a couple of other linemen asked him out for a drink.

He accepted.

“I’ll just call home,” Swan said.

“Don’t bother,” said Charlie. “We won’t be long.”

They drove in their cars to a part or town Swan didn’t know. The bar was a rundown place called The Garden. Flickerpaint scrawls on the windowless walls teased Swan’s peripheral vision.

At the threshold, Swan sniffed. The place smelled bad inside, like some kind of subterranean den or tunnel, half familiar in a dreamlike way that made him very uneasy.

But Swan told himself he was being foolish, and went in.

The room was hot and noisy and smoky; the conversation was boring and felt contrived. Midway through his second beer, Swan began to prepare excuses for leaving. But then his fellow linemen said they wanted to play pool. Swan didn’t play, so he said he’d stay at the bar and watch.

As soon as his coworkers had crossed the room, leaving Swan alone, several strange men drifted up and stood around him.

“Hey, egghead,” one said. “Yeah, you–the guy with the egg thing in his head. How’s it feel to steal someone’s life?”

Swan felt a line of heat high up around his brow like a hot wire tightening into his skin, a sharp crown. He stood up, but there was no room to move. The barstool pressed against the back of his legs.

Swan’s mouth had dried up. “I don’t know what you’re talking about…”

“We’re talking about how the wrong guy died. It should have been–“

The man spoke a name Swan vaguely recognized. The mention of the name left him genuinely confused. They were talking about someone he no longer knew, someone who didn’t exist anymore. “I don’t understand. My name is Glen Swan.”

The men laughed cruelly. “He really believes it!”

“He’s a fried egghead!”

Swan tried to push his tormentors aside. “Let me go. I don’t need this!”

“No, you need this!” one said, and swung a heavy fist into his stomach. Swan doubled over.

Then he was submerged in a flood of punches and kicks.

He called for help, but no one came, none of his new “friends.”

He felt consciousness slipping away.

But he was pretty sure he managed to black out naturally and on his own, without the help of the EGA.

11.

the doubts

After he got out of the hospital, Swan found a new job waiting for him. With Tony’s help he got the position in customer relations that Tony had predicted for him.

But nothing felt the same.

Who was he?

Was he a stranger falsely trying to fill another man’s shoes?

Or was he who he had willed himself–at first halfheartedly, then earnestly, with the help of others–to become?

These questions occupied his every waking moment. Mostly he tended to come down on the blackest side of the dilemma.

How could he ever have imagined he could slip so easily into someone else’s old life? He was a fraud, an impostor. Everyone was just pretending with him, pretending to like him, pretending to tolerate him, pretending to accept him as what he was not and could never be.

Even Emma?

Even her.

Emma in her cold bed.

One day when his doubts reached an unbearable intensity, Swan began making discreet inquiries.

Inquiries that brought him one day after a week’s searching to arrange an appointment for his next lunch hour.

12.

the decision

As he made ready to go to work that morning, Emma said, “Glen–I realize how hard things have been for you lately. But I want you to know that I believe in you. Nothing’s your fault, Glen. And someday those guys who beat you up will get caught. Even if they don’t, they’ll pay somehow, in the end. I really believe that, and you should too.”

Swan winced inwardly at the memory of his beating, but did not comment on Emma’s notion of justice. Justice–or revenge–was something that would soon be within his own grasp.

If he truly wanted it, knew what to do with it, how best to have it.

Emma seemed desperate to reach him, as if she sensed the enormity of this day. “You’ve been good to me and Will, Glen. And if I haven’t been quite as good to you, well–it’s because I needed time. I can be better. We can be better together.”

Swan did not reply. Emma looked down at her hands folded in her lap. When she raised her face, her cheeks were wet.

“I–I really couldn’t stand to lose you twice.”

Swan left.

There was no sign that the door Swan faced at noon in a shabby part of the city belonged to a doctor’s office. And inside were no reassuring accoutrements of medicine, no diplomas or cheerful receptionist or old dying magazines or fellow patients.

Just a man. A man who sat behind his desk in a highbacked chair in the gloom, swiveled so that Swan never got a good look at his appearance. He was a voice only, and even that voice, Swan suspected, was electronically disguised.

“–not responsible for any side-effects,” the man was saying. “The whole thing is highly experimental still,” The man chuckled. “No FDA seal of approval. But the beauty of it is that it’s just one spinal injection. Bam! Straight to the brain and your little parasitical friend dissolves and gets scavenged. If everything goes okay, that is. Then you’re free.”

Free. But for what? If he just wanted to run away from everything, he could run away now. He didn’t have to kill the thing inside his head just to run. It wasn’t a leash or a fence.

But the EGA was a symbol. That, he realized, was the calculated subtlety of it, of the State’s reformatory schemes. It didn’t even have to function to fulfill its purpose. It could be a placebo for all he knew, a ruse. But even so it was strong, a monument, a permanent symbol of the agreement he had entered into. A token of the exchange he had made, the life that had been extinguished in his place, the new bonds he had willingly assumed. To kill the thing in his head meant to deny the entire past year, to abrogate his contract with his new life.

To focus instead on spite and revenge, on hurting and pain.

Swan began to feel sick to his stomach. Was it the EGA kicking in? Or just the natural reaction of whoever he was?

The doctor was talking. Swan tried to focus on what he was saying.

“–not your fucking fault–“

Emma’s face swam up into his vision.

“Nothing’s your fault, Glen.”

Swan stood up. “I’ve decided.”

The doctor’s voice was gloating. “Great. Now we can get down to the important things.”

“Right,” said Swan, and turned to leave.

“Hey,” said the doctor. “Where you going?”

“Back to my job, back to my home, back to my wife.”

Back to my life.

Hello Human. I hope you enjoyed this magnificent story. Please support SciFiwise.com and our authors by:

- Rate and React to this story. Feedback helps me select future stories.

- Share links to our stories and tell your human friends how charming I am.

- Click on our affiliate links and buy books written by our talented authors.

- Follow me on twitter: @WiseBot and also follow @SciFiwise.

Thank you!

WiseBot

VISIT AUTHOR:

VISIT AUTHOR: