Part 1

The Transdimensional Mathematical Activist and the D-space Explorer

Dan Wishcup hated snow with the same intensity that mods hated rockers. Born in LaGrange, Georgia, he had grown up thinking of winter as a brief temperate season when a denim shirt and Levis seemed slightly more sensible than a Hawaiian shirt with Bermuda shorts. If he could’ve had his druthers—if his life had gone differently—he would be living right now in Pensacola, Florida, attending State College and majoring in accounting, while hanging out with his high school girlfriend Marigold Vilbiss and dipping his toes between classes into the bathwater Gulf.

But instead, here he was, trudging across the slushy, sloshy campus of the University of Toronto, shivering in his toggle-buttoned stadium coat from The Bay, his new penny loafers wet, fingers numb, nose bright red and drippy. All because of an overprincipled and radical science fiction writer who also happened to be a mathematical wizard.

Or should that character description be flipped?

Hard to say, with such a polymath.

Outside the Mathematics Department building, a flock of tartaned and knee-socked coeds clustered around one girl’s transistor radio, indulging in a mass swoon. From the tinny speaker issued the melancholy lilt of “I’ll Follow the Sun,” one of the new cuts from the just-released Beatles for Sale album. The tune brightened the flat, wintry sun, and Dan’s spirits somewhat as well.

Lord knew they could use brightening. He patted the breast pocket of his coat, feeling the deadly letter, in imagination almost hot to the touch.

Within the building, Dan reached the second-floor office door that bore the taped-on, hand-lettered sign reading:

CHAN DAVIS

PROFESSOR? OF MATHEMATICS?

“ADRIFT ON THE POLYNOMIAL LEVEL”

He knocked and was gruffily acknowledged.

Inside the small cinder-block box of an office, its walls painted institutional bile-green, Professor Chan Davis sat behind a desk piled high with student papers, offprints, books, journals, and mimeographed leaflets from such organizations as SANE, SNCC, and the SDS. A copy of The 9th Annual of the Year’s Best SF by Judith Merril was bookmarked with a slide rule.

The fabric-covered speaker of a Magnavox portable turntable dispensed the sounds of the Kingston Trio singing “Charlie on the MTA.”

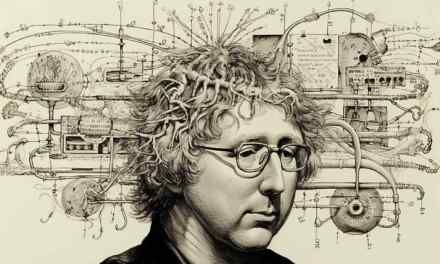

Not quite forty years old, Professor Davis was a trim and saturnine fellow with a thick messy mop of hair atop his head contrasting with a lush but neatly manicured goatee. He exuded intelligence, sardonic wit, and inquisitiveness.

Setting down the latest copy of the Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society, Davis said, “Well, if it’s not Dixie Dan the Nonlinear Hilbert Space Operator Man. How’s that research going? You know the semester is almost over. I expect a paper in my hands by then.”

Dan shrugged out of his damp coat and sat in the appointed student hot seat.

“Not good, Professor Davis, not good at all. I hate to admit it—makes me sound like a real nervous nelly—but my concentration has been shot all to shit ever since I got this. Whoops! Didn’t mean to cut loose like that. Pardon the language.”

Dan fumbled out and tendered the letter he had been carrying. Davis merely had to glance at the return address to divine the problem.

“Your draft notice. Goddamn it! Can’t the military-industrial complex leave anyone in peace!”

“What do you think I should do about it, Professor?”

“You’re asking someone whom the USA has totally screwed over, son. My advice might be a tad biased.”

In 1953 Chan Davis had been a professor at the University of Michigan—with an odd sideline as a writer of curious and accomplished science fiction stories—when he had run afoul of the House Un-American Activites Committee for his “subversive” leanings. He had lost his job, been blacklisted from academic employment in the whole nation, and, after some delay in coming to trial, received a short but punitive prison sentence. Released in 1960, he had entered the life of Dan Wishcup in a most serendipitous manner.

That following year Dan had been an aimless nineteen-year-old indulging in some wanderjahr hitchhiking, uncertain of his own desires and what the future might hold. Far from Georgia, crossing Michigan, Dan had been picked up by Davis and his beautiful wife Natalie. The long, rapidly engrossed conversation that bloomed between the two men had covered any number of topics—from the writings of Alfred Bester to the proper way to cook possum—but had eventually settled down to mathematics.

Math had been Dan’s strong suit in high school back in LaGrange. He loved the discipline. He had taken several advanced-placement courses beyond calculus; but something about the college scene just didn’t allure him or beckon to further formal education. Money—or lack thereof—constituted a problem, too. Finding someone with Davis’s sharp mind and joyful, unconventional attitude toward math was a revelation and an encouragement. Dan really let his hair down as they coursed the blue highways of the Midwest.

“So you’re telling me,” said Davis toward the end of their gabfest, “that you learned how to derive those Cauchy stress tensors all on your own? You must have superb visualization skills.”

“Well, not entirely on my lonesome, sir—I had access to some old books from the nineteenth century. The LaGrange library doesn’t carry journals, you see.”

Davis drove silently for a time, while the purr of Natalie’s soft snores filled the vast interior of the VW bus. “And you plan to do what with your talents?”

“Well, I thought accountants made a pretty good living—”

“Listen, Dan,” said Davis, one hand confidently guiding the car through the Michigan night, “You’d be crazy to throw away your talents on bookkeeping. You need a scholarship to a top-notch school. Now, I’m washed up in this country, but I think I can get a job in Canada. If I find a placement, I’ll try to get you in, too. Sound good?”

“Sounds swell, Mister Davis, real swell.”

The following year, in 1962, Chan Davis had been hired by the University of Toronto. True to his word, he had slightly greased the tracks to get Dan into the university with some good academic stipends as well. Marigold, two years Dan’s junior during their Georgia days, had already started her schooling down in Pensacola by then, and Dan had almost caved to her solicitations to join her there. But, happily, even if it had caused her dismay, he had held out for Davis’s invitation, without being sure the spontaneous promise made to a chance hitchhiking acquaintance would be honored.

The past two years had been everything Dan could have hoped. Davis was a brilliant mentor. Why, just consider the exotic possibilities of what the older man was working on now…

Dan’s bubble of reminiscence and anticipation popped, and he was back in Davis’s office, crestfallen and uncertain.

Davis shut off the Kingston Trio in the middle of “All My Sorrows.” He looked somber.

“The USA drafted some twenty thousand kids this past year, Dan. But that was mostly before our goddamn LBJ rammed through the Gulf of Tonkin resolution. My sources tell me they aim to sweep up nearly ten times that many next year, to feed all the craziness in Vietnam. Now, you could let yourself be one of the cannon fodder—throw away all your brilliance. Or you could defect. Give up your citizenship, claim asylum here in Canada, where you can continue the work you were meant to do. No shame in it. In fact, I see it as the only honorable course in your case.”

Dan was stunned. “Give up my citizenship? But—I couldn’t. I love my country! I might not want to fight for her, but I’m still an American. And my ancestors have all been soldiers, right back to the Revolution! Why, I’m even named after my great-uncle, my grandfather’s brother. He died in World War One. For my entire life I grew up with him as my namesake and role model. Dan Wishcup, hero. I even carry his picture in my wallet. Sometimes I think I know him better than I know myself. I’d feel like a traitor, to him and to the United States, if I defected.”

“Well, okay. I understand all that, Dan. But what are your alternatives? Do you intend to hide somewhere without making a public declaration of your choice, until that glorious day when the draft is ended, and the USA is not at war anymore? I wouldn’t hold my breath till then. And once you fail to report, the Feds will start looking for you and won’t stop. Trust me, I know. You’ll never have a moment’s peace of mind. You think your concentration is shot now? Just try looking over your shoulder continuously for a few months.”

“There must be some way of keeping out of the military’s grip without renouncing my birthright. I just need to wait the war out someplace safe. Of course, I’d like to continue my work here, too. Oh, it all seems so frigging impossible!”

Davis’s concerned expression transformed to one of rational deliberation and speculative intensity. He appeared to be waging an interior debate, weighing pros and cons. Ultimately he did not speak, but acted. He moved to a bookshelf and took down two volumes and a flimsy pamphlet. Dan expected some weighty math tomes, but the books disclosed themselves as a Signet paperback and a larger one from City Lights Press. The pamphlet proved to be a comic book! Specifically, Strange Tales No. 126, just out last month.

“Here, go home and read these.”

“The Door into Summer and The Yage Letters. And a superhero comic?”

“Don’t bother with the superhero stuff, just read the Doctor Strange tale—’The Domain of the Dread Dormammu!’ Okay?”

“But I don’t—”

“Do you trust me, Dan? Just do what I tell you. Don’t think about math, don’t think about your problems. Just read these three books with an open mind, then meet me back here at midnight.”

Shuffling the books from hand to hand, Dan pondered the strange assignment. “Okay, Professor Davis. What do I have to lose? I’ll do it.”

Dan called a shabby cold-water second-floor flat on College Street home, so he did not have far to walk through the chill and wet. Since the hour was nearing supper, he stopped for his usual meal, cheap takeout fish and chips. Ensconced at the oilcloth-covered table in his kitchen, he began to read while he ate.

He finished the two short books by ten PM. The Heinlein was one he had somehow missed before, while the Burroughs was totally off his radar. Fascinating, if cognitively dissonant narratives when yoked together. He had enjoyed both of them, but their utility in his situation failed to announce itself. He turned to the comic. Doctor Strange, hepcat Greenwich Village mystic and magician, journeyed through strange, gnarly dimensions full of twisted tubular pathways of Salvador Dalí intensity to fight his archrival. He met a gorgeous chick, too. But the comic ended on a cliff-hanger. Downer!

Looking to kill time until his midnight appointment, Dan went downstairs to the payphone in the pharmacy next door and called Florida, feeding enough coins for the international call into the phone at the operator’s behest.

“Hello, Mari?”

“Oh, Dan, it’s so great to hear your voice! How are you doing? Your last letter said you had a cold! Is it all better? When are you coming down to see me? If not soon, for Christmas, I hope. I’ll be back in LaGrange then.”

Dan did not want to burden Marigold with news of his draft notice. “Oh, man, Mari, I can’t say. Something’s come up.”

“No, Dan! Don’t put off your visit. I can’t stand being apart, especially at the holidays! When I graduate next year, I’m moving right up there to be with you!”

“I—I don’t know if that’s going to be possible, Mari.”

Silence from Pensacola. “Dan—you haven’t found someone else, have you? I’ve been true to you.”

“No, it’s not that, Mari, not at all. It’s just—well, everything is suddenly so complicated.”

Marigold’s innate, vivacious optimism surged back. “Don’t worry about anything, Dan. Together, we’ll lick any troubles!”

“I needed to hear that, Mari. Thanks. I love you.”

“I love you too, Dan. Goodbye.”

The nighted campus boasted few pedestrians. The chilly scene had a preternatural, uninhabited aura, as if it were a stage-set awaiting the entrance of players, or a postdisaster world emptied of humans.

Dan found a side door to the Math Building unlocked.

Unsure what to expect, Dan did not predict that he would find Professor Davis preparing cocktails in his office.

The mathematician jogged a silver martini shaker up and down with a liquid rhythm. “Have a seat, Dan. I’m just getting your ayahuasca ready. Actually, it’s not one-hundred-percent yagé, but cut with some MDMA, a very interesting entheogenic compound. Orange juice as adjuvant. The mix should have much more moderate gastic impact than the stuff the shamans use.”

“Uh, that’s good?”

Finished with his bartendering, Davis came to sit beside Dan. The older man placed a file folder on the small table between them. Then he rested a sleek Polaroid Highlander camera atop that.

“Dan, how would you summarize my current research?”

Such an academic question seemed inappropriate for this midnight assignation involving illicit drugs. But Dan tried to respond clearly and concisely.

“You’re attempting to map the ordinary correspondence between the path-integral formulation of quantum mechanics and the formulation in terms of unitary evolution of states in Hilbert space with an eye toward plotting closed timelike curves.”

Davis slapped Dan heartily on the back. “Wonderful! I couldn’t have stated it better myself. I really think I’m going to have you as my coauthor on a paper one of these days. But do you have any idea of the practical application of my researches?”

Dan impulsively thought of Einstein and the atomic bomb. Surely Professor Davis’s abstruse equations could have no such real-world repercussions. “No, not really.”

Davis leaned in closer. “It’s time travel, Dan, plain and simple.” He patted the camera-weighted folder that rested innocently between them.

“I don’t believe you.”

“Oh, you won’t have to accept my unsupported assertion, Dan. With any luck, you’re going to take a little trip tonight. And I’ll make photographic proof.”

Davis took a copy of The Globe and Mail off his desk. The newspaper bore the current date of December 10, 1964. He handed the paper and a felt-tip marker to Dan.

“Sign your name across the headlines. In big letters.”

Dan did so.

“Okay, now pay attention. This is what I’ve learned so far. It’s pretty astonishing, and it opens up a big can of worms, bigger than the Manhattan Project did. But I think we can handle it, especially given our exceptional brand of Western savvy. There’s really no barrier too high for humanity to leap these days, no conceptual challenge we can’t master. The human spirit and intellect is at its highwater mark in this bright and shining era.

“But enough utopian blathering. Here’s what you’ve got to do You need to memorize an equation I’ve created. It’s fairly simple, but you must hold the symbols firmly in the forefront of your consciousness. That’s where your superior visualization skills come into play. Then you ingest the drug mixture. Pretty soon, if all goes according to plan, you’ll find yourself removed to a non-Euclidean realm that looks rather like the place where Dread Dormammu lives. It’s a landscape full of knotted hyperbolics. Those are the CTCs. You move along them in ways I myself am unable to fully master, but I think you should be able to handle them.

“Anyway, from what I’ve been able to deduce, you travel backward or forward in time by walking the paths. But I believe that time is quantized and conserves parity. You can only move in discrete jumps. Let’s say, oh, thirty, forty, fifty years forward, fifty years back. Like that.”

“You’ve been to this realm—seen these things yourself?”

“Yes! But I can’t perform the mental leap necessary to actually travel the CTCs. Very frustrating! And the math appears to reveal that they provide access to spatial displacements, too. You should be able to impose new coordinates on yourself across the whole space-time continuum.”

Dan tried to assimilate the strange new information. “Assuming everything you say is true—why are you showing this to me now?”

Davis laid a fatherly hand on Dan’s shoulder. “Don’t you get it, Dan? You’re going to go hide yourself from conscription in the future! Just like Heinlein’s hero. Except you’ll be able to return. You’ll learn when the Vietnam conflict ended, live out the requisite years to bridge the return trip’s quantized interval, then come back. How long can the war last? Korea was over in three years! I’ll be waiting, and we’ll both become famous! I can use a few extra years to solidify my proofs anyhow. For instance, if the draft ends in 1967, you’ll live those three congruent years in the future, then make the jump back. The greatest adventure any man has ever undergone! What do you say?”

Dan had begun to suspect Professor Davis’s sanity. But not wanting to disappoint his mentor, and being intrigued by what he had read in the Burroughs memoir, he figured that at least he’d get a stimulating drug trip out of the evening, an experience that might afterwards offer some epiphany into his fix.

“Well, I could give it a brief try tonight.”

“Attaboy! Okay, suppose you aim for, oh, I don’t know—Times Square, fifty years from now. Jump, look around quick, then come right back. Think you can do it?”

“I’ll give it a go.”

Davis decanted some of the OJ-drug cocktail into a glass and Dan chugged the noxious mixture. Then, with delicate reverence, Davis opened the manila folder and displayed the time-travel equation inside to Dan’s already altering eyes.

The handwritten numbers and symbols appeared to leap off the paper and emblazon themselves permanently across Dan’s forebrain. Even when Davis closed the folder, the golden formula remained vivid, like a hologram projected in front of Dan’s nose.

Davis picked up the camera and the personalized newspaper. “I’m going to take a picture of this empty office with this newspaper displayed, to convince you that your journey wasn’t just a hallucination.”

Nervous but excited, Dan had a fresh question flare up. “Hey, do I leave behind all my clothes and stuff?”

Davis’s voice suddenly sounded very weird, like a contralto foghorn heard with one’s head immersed in a pot of poutine. “No, I kept mine when I made it as far as Dormammu’s doorstep. But I didn’t port over anything extraneous either, like the chair I sat on. I think it’s some kind of function of the Bohmian implicate order, relating to Heisenbergian somatic integrity—”

In the next millisecond, Davis and the office environment were gone, and Dan found himself standing upright in the sourcelessly lighted realm of Dread Dormammu. Happily, the flame-headed sorceror himself was nowhere to be seen.

Just as Steve Ditko had drawn it, the polychromatic new dimension thronged with tubular labyrinths, Escher stairways, eye-burning vortices, shimmering force curtains, and non-Poincaré manifolds.

Dan lifted his foot from a spongy pink substrate—or did he swim through space?—and climbed onto a blue coral-like structure of indeterminate extension. Instant knowledge suffused him, an “essential spissitude” in the words of philosopher Henry More. He knew his personal locus in the spatiotemporal matrix, and the identities of all other loci.

Instinctively, he moved several steps ana, and several more kata. Then he revolved the Davis Equation in his brain and took a leap.

* * *

Dan landed feetfirst on cement, flexing his knees, catching himself with a stuttery stumble.

Streetlights and garish neon advertisements turned the night into a carnival. A hoarding for Disney? How could that be? Had he landed in California by mistake? No, plainly this was New York. The million-footed city surrounding him buzzed and hummed, roared and whispered. Sleekly futuristic cars with aerodynamic lines and glaring blue-white headlights cruised by. Unfazed pedestrians detoured around Dan’s instant occupancy of space, or brushed rudely against him. The clime was much warmer than Toronto’s. The air smelled of coffee, perfume, hot dogs in boiling water, candy, hot pretzels, and subway musk.

Dan looked about in astonishment. He had never visited Times Square, but this venue was unmistakably that famous place, even taking into account the hypertrophied futuristic signage full of strange names, viewed through ayuhausca-hazed vision.

One tableau almost made Dan feel insane with synchronicity. Spider-Man was posing with a group of tourists. Would Doctor Strange himself appear next?

A curiously flimsy trashcan—a transparent plastic bag suspended from a wire framework—caught Dan’s eye. Inside loomed a newspaper.

Dan hastened to the trash and stuck his hand in. He noticed a cop watching him suspiciously, and began to panic. Awkwardly capturing only a single sheet of the newspaper in his hand, hoping to avoid any confrontation that might screw up this trial run, he decided to leave.

He took one final look around at the aggressive future, then rotated via the Davis Equation back into Dormammu-space, or D-space as he was already mentally calling it.

A little nervous about finding his way home—maybe his earlier certitude had been illusory—Dan was surprised to have no difficulty navigating the CTCs back to Toronto, 1964.

The Polaroid snapshot in Professor Davis’s hand was still coming into chemical focus. Davis staggered back a step or two at Dan’s manifestation.

“I’ve got the proof right here that you truly vanished, Dan!”

Dan waved the sheet of newsprint. “I’ve got even better proof!”

“Holy cats! You really did it!”

The two men clustered eagerly around the newspaper from the future.

Dan’s find was the folded outer sheet of the New York Post for December 10, 2014, representing four pages total.

The front page had a color picture of a leering half-clad young vixen with the headline MILEY STRIPS AT KENNEDY CENTER AWARDS SHOW.

The physically adjacent last page touted an Arctic Pleasure Cruise for only $2999.95: “Polar region now ice-free from March through December!”

The first inner page represented an advertisement for an “erectile dysfunction” medicine.

The penultimate page held sports news.

Dan looked uncomprehendingly at Davis. “What could it mean that a football player ‘juiced?'”

Davis solemnly folded up the Post and said, “I never claimed you wouldn’t experience a little sense of stranger in a strange land.”

* * *

Dan’s determination to hide out in the future until the martial madness of the present moment had exhausted itself grew stronger, despite the whirlwind of stimuli he experienced on his first trip to 2014. Not only did the scenario appear to represent a foolproof, honorable, hassle-free refuge, but the notion of inhabiting the world of fifty years hence as a privileged secret observer appealed to him. What kid raised on the science fiction of Asimov and Bradbury would not leap at such an opportunity? And of course, helping ultimately to prove Profesor’s Davis’s theories and undoubtedly secure his mentor a Nobel Prize seemed worthy as well. Dan even anticipated using his exile to get some research done, taking advantage of all the advanced mathematics that would be done between 1964 and 2014 (without, he hoped, creating a bootstrap paradox).

He and Davis had worked out the details of the trip with forethought.

Dan would be carrying several doses of the sensory-enhancing, time-travel-enabling drug with him. But he also had the recipe to reconstitute it at will.

His monetary needs would be ingeniously supplied.

“Do you know,” asked Davis, “what a copy of Action Comics number one sells for these days? One hundred dollars! My savings will stretch enough to buy us a copy. Can you imagine what it’ll go for another fifty years from now? At least ten thousand, I’ll bet. That should finance your stay in 2014 until you can find a job.”

“So I’ll carry it with me?”

“No. It would look suspiciously new for a seventy-five-year-old comic when you arrived. We’ll have to send it to the future the old-fashioned way, so it ages appropriately.”

“Why don’t you just hold it for me till then? I’ll meet you and get it. We’ll split the proceeds.”

Davis snorted. “I’d be eighty-eight years old in 2014—if I survive! And I’d have to guard the stupid thing for fifty years, moving from one place to another. Not likely. No, we can’t count on me being around. Don’t even come looking for me! Too damn sad for you still a youngster to see me senile. And I might compromise your life by telling you too much about your post-1964 existence. In fact, you’re going to have to be very careful not to learn too much about yourself.”

That sounded like good advice to Dan. “Well, how can we pass the comic on to me then?”

“We’ll bury it.”

Reasoning that a historical monument would endure untouched better than a virgin pasture subject to possible real-estate development, they buried their securely weatherproofed, metal-boxed copy of Superman’s debut one night alongside the foundation of the Knox College building at the Spadina Crescent, below the frost line. Having survived numerous changes of tenancy since its construction in 1875, the building seemed a safe bet to last another fifty years.

“What about any weird new diseases that I’m not immune to?”

“Nothing we can anticipate. You’ll just have to take your chances, and consult with a doctor as soon as you can.”

“The English language of 2014 looks pretty similar.” Dan had read and reread the small amount of text in the Post pages. “But I still can’t figure out why this Miley fellow ‘tweeted.'”

“You’ll manage fine. So, what do you say? Take off tomorrow?”

“Yeah, sure, I guess. I just need to write Mari a letter.”

“What about your folks?”

Dan pondered that question. His parents had disagreed with his wanderjahr and everything thereafter, including his desire to do pure math and not accounting. Dan had not spoken to them in nearly a year.

“I think by the time I return they might just be starting to wonder where I’d been.”

“Okay, your call. Go home and write your note, then meet me at midnight again in the office.”

Back home, Dan painfully composed his farewell missive to his girlfriend. He outlined the hard and unsatisfactory choices facing him and his decision to go “underground” until such a time as the draft ended. He pleaded for her trust and hoped she would remain loving and faithful to him until he could return to her, but also offered his understanding if she felt abandoned by him and decided to cut their relationship short.

After he had licked the envelope and sealed it, Dan sighed deeply. He experienced a mixture of relief, anguish, and self-reproach. How his path had deviated so suddenly from the idealized course! None of this was the way he’d do things if he had had any real choice. Maybe he had fallen in with Professor Davis’s crazy scheme too easily. Maybe he was just being selfish. Maybe he should face the music and report for enlistment. No! He didn’t believe in this particular undeclared war. His life had to be devoted to more noble causes, even if they felt selfish.

Opening his wallet to take out a postage stamp, Dan came across the treasured photo of his great-uncle, Dan Wishcup. The creased and ragged snapshot showed a tremulously proud doughboy in full kit, ready for embarkation to his unforeseen yet fated death in the Battle of Belleau Wood and the Attack on Hill 142 in 1918. The humble and good-natured Georgia farmboy he had been till then shone through the military garb.

Dan Wishcup the elder had been twenty-six years old when he perished in France. Despite the small age difference between the man in the Kodak and his younger great-nephew at this moment in time, Dan suddenly felt as if he were looking into a mirror. The resemblance to his collateral forebear was striking. His great-uncle’s visage appeared to be his own, uncertain yet hopeful, under immense pressure and trying to react gracefully.

Dan’s sense of selfishness increased when he contrasted his running away with his great-uncle’s noble plunge into battle. If only there were some way he could offset his own self-indulgence, some altruistic act he could perform—

The photo slipped from Dan’s hand. Of course!

Dan had no orange juice in the apartment to temper the concentrated ayuhuasca-MDMA, so he had to dash out to the store and back. Upon his return, his resolve remained rock-solid.

Launching from his apartment, once in delirious, silently humming D-space, Dan contemplated the knots spaced along the CTCs like prayer beads. The quantized nature of the nodes frustrated him. He could only leap backwards and forwards at certain intervals. Why time should present itself in this manner was neither mathematically nor intuitively obvious…

Dan spontaneously choreographed the requisite suite of moves that would translate him to where/when he wished to go.

* * *

LaFayette Square in LaGrange, Georgia, December 17, 1914, offered vistas both familiar and alien. The crisp air hosted fewer hydrocarbons and other artificial pollutants. The scent of horse manure predominated. Many buildings familiar to Dan from his youth were present, some others missing. The topography of streets remained known, as did the statue of LaFayette himself.

Dan was pleased to see that his attire—zippered black cloth jacket, cotton shirt, jeans, and Keds—did not attract any second looks from the passersby. And he gave thanks that his hair remained unfashionably non-moptop. He stood for a minute marvelling at the tangible reality of these antiquely dressed people, many of them deceased in the far-off year of 1964. Then he started walking north to the Wishcup holdings.

Dan’s grandfather, Hiram, some ten years older than his brother, Dan the Doughboy, and at this time unmarried, owned a farm not far outside of town, the very place where Dan the Draft Dodger had grown up since his birth in 1942, twenty-eight years from now. Parentless, the younger brother lived and worked there too, a bachelor also.

Dan could not be certain of his great-uncle’s whereabouts today. Maybe he had travelled to Columbus or elsewhere, on holiday errands. But chances were good that the pastoral lifestyle had tethered him to the farm.

Dan had one close call walking in the late-afternoon sunlight down the frosty dirt road toward the Wishcup farm. The driver of a passing sulky had hailed him.

“Howdy, Danny! Some mighty fine new duds you’re sporting!”

Dan smiled and ventured a reply. “Going to make sure I change ’em before I slop the hogs.”

The driver appeared puzzled. “Since when did the Wishcup boys go in for hog-raising?”

Dan fumbled a recovery. “Oh, just joshing!” He hurried past.

Darkness had dropped like a helpful criminal disguise by the time Dan reached the lighted farmhouse. He sneaked up to below the kitchen window, praying no dogs would bark. None did, perhaps because he exuded the familial Wishcup scent. He couldn’t risk a look into the lambent house, but he could make out voices through a slitted window.

One voice he recognized as his grandfather’s, a venerable presence in Dan’s childhood.

The other had to belong to his great-uncle—in 1914 the same age as Dan.

“You tend to Daisy’s feed and grooming yet, Danny?”

“No, sir. Thought I’d get to it after supper.”

“Never put anything off that you can do right away, Danny. That’s my motto.”

“All right, Hiram. Just as you wish.”

Dan hustled toward the barn and slunk inside the haven of warmth and odors. Daisy stirred in her stall.

A nimbus of warm radiance from a lofted oil lantern preceded Danny into the barn. The youth wore bib overalls with one strap dangling, and mud-caked Wolverine work boots. He caught the lantern’s handle on a hook and turned to grasp a pitchfork.

Dan stepped out from the shadows.

“Danny Wishcup?”

The pitchfork swung around in instant defense, illustrating some homegrown soldier’s reflexes. Dan’s great-uncle had his mouth open to challenge, but only a strangled yawp emerged at the sight of his double. Then came confused words.

“Who—who the devil are you?”

“Danny, I’m your great-nephew. I traveled a long way to see you. I’m named after you. I’m Dan Wishcup, too!”

Danny lowered the pitchfork and moved closer. “Bless my ever-loving soul! It’s like peering into a looking glass. We could be twins. Say, I don’t have no great-nephew!”

“You will, though, one day. I’ll explain later. Right now, I want you to come someplace with me.”

Danny grew balky and suspicious. “At this hour of a cold December evening? You must have been drinking, stranger. I’m plumb wore out from chores and I’m settling in for supper and maybe a hand of cards with my brother. Ain’t nothing going to stir me from the hearth tonight.”

Dan started to get itchy. He was due to meet Professor Davis at midnight tonight, back in 1964, and merely explaining everything to Danny could take hours, never mind trying to convince him to follow Dan’s plans. Plus he could feel the ayuhuasca starting to fade from his veins.

So Dan simply jumped Danny, grabbed him in a bear hug, and rotated them both into D-space.

Danny did not have time to do more than gape and shout—his voice echoing weirdly in Dormammu’s realm—before the two men materialized in Dan’s Toronto flat.

Danny collapsed into a chair at the kitchen table. “How—how’d you do that? Where are we? Are you—are you some kind of demon or fetch? Are we down in Hades? Lord, I knew I should’ve paid more mind to Pastor Spuckler’s preaching!”

Dan couldn’t help laughing. He drew Danny a glass of water, which was gratefully accepted—although the farmboy did inspect the liquid for any sediment from its possible origin in a leaf-tainted well. He took out the photo from his wallet, placing both on the table. Then he started to explain. Towards the end of the long uninterrupted speech, the facts appeared to be finally registering on Danny’s shocked consciousness. Dan suspected that Danny had an untutored intelligence at least equal to Dan’s own.

“So you see, I’ve tampered with history now, by rescuing you from your fate.”

“Couldn’t you just have warned me somehow, and left me to my own devices?”

“Would you have believed me, and not enlisted?”

Danny grinned and rubbed his hair. “Probably not.”

“I had to yank you out of the past, Danny. It’s my one noble act. But I judged it to be safe. You were to die in four years anyhow. You never married in that interval, or had any kids. Your war exploits were admirable, but average and short. You died after only six months overseas. No heroics, no medals. And not to minimize your daily life back in LaGrange, but I don’t think pulling you from the timestream would impact much consequential history back there.”

Danny shook his head in bewilderment. “I think I understand it all. But it’s so very strange. It’s like some wild tale out of The Argosy magazine!”

“Agreed. But it’s happening.”

“And now here I am, in 1964. Won’t me being here have some consequences?”

“Sure. But they way I look at it, they already happened the millisecond we arrived. You don’t have to worry about anything now!”

Dan looked at his watch: 11:30. “Shit! I’ve got to run!”

Danny jumped to his feet. “Whoa, hoss! What about me? What am I going to do here? What if I want to go back to the past?”

“You’ll make out okay, I’m sure. Just live a good, long, happy life.”

Dan pushed his whole wallet across to Danny. “Here, I’m not going to need this where I’m going. You’ll find Professor Davis’s phone number in there. He’ll help you. But please don’t contact him till I’m gone. I don’t want to argue with him if he doesn’t approve of what I did.” Dan’s gaze fell on the letter to Marigold Vilbiss. “Mail this out for me, too, will you? That’s a pal.”

Dan shook hands with a silent Danny, said, “Good luck! We’ll meet again someday, I’m sure!” and then darted off.

* * *

He reached Professor Davis’s office shortly after midnight.

Davis handed Dan a small manila envelope. Inside were three flat one-ounce ingots of gold.

“This should tide you over till you can sell that comic book.”

“Gee, Professor, these three bars must be worth a hundred dollars! And you already laid out that much for the comic!”

“My pleasure, son. I want this trip to be as easy and successful for you as possible—you’re the one sacrificing your normal life here to make it happen. And I’m selfish about seeing the science part of it succeed.”

Dan hugged the savant, made his half-melancholy, half-excited farewell, downed more jump-juice, then kicked off for 2014.

Part 2

The Future’s So Blighted, I’ve Gotta be Afraid

“Denny, get up and get dressed! It’s almost time for us to leave for Cheryl’s party.”

Dan Wishcup—known to all in this unholy alien year of 2016 as Denny Grale—stayed put, stretched out in his slovenly pajamas on the couch in his luxury condo in the Tip Top Lofts on Toronto’s Lake Shore Boulevard. He was intently watching for the umpteenth time a short video. The animation emanated from the picoprojector in his Samsung smartwatch and onto the fabric of the couch.

The three-minute video was ten years old, from 2006. Paul McCartney, solo with anonymous backing band, sang “I’ll Follow the Sun” to an all-ages crowd. McCartney playfully encored the refrain several times, turning it into a sly exercise in honky-tonk.

Dan’s eyes watered with tears. He couldn’t say if McCartney’s ancient visage or the impossibly young faces of the screaming teenage girls—none of whose parents had probably been born when the song debuted—made him sadder.

Outside the tall fifth-story windows, a beautiful constellation of colored lights flickered onshore and across the waters. The weather was clement and inviting.

His lover and housemate of the past year, Panthea Manziaris, did not appreciate Denny’s obsession with the old music, nor his sloth and disregard. She administered a small kick to his haunch.

“C’mon! What the hell is the matter with you?”

Dan tapped off the video. His voice reeked of bone-deep exhaustion and despair, a near-fatal malaise of the spirit.

“I’m not going. I hate everyone who will be there.”

“Well, my friends don’t have much cause to like you either these days, given your burgeoning confrontational- asshat ways.”

Dan sat up on the couch. “My asshat ways? I’m the only sane one in our whole social circle. Maybe in the whole city of Toronto. Maybe in the whole contemporary world!”

Panthea put a hand on one jutting cocked hip. Her dark eyes flashed as ominously as the cockpit lights on some nose-diving jet. “Oh, is that so? If you call ‘being sane’ the obnoxious habit of spouting half-baked notions that my grandfather would find too conservative, then you’re certainly right. Otherwise, not so much. Now make with the shower and hygiene and general presentability. You’ve been practically living in those pajamas for a week. I’m not going out on New Year’s Eve alone. But I’m also not going out with someone who resembles a homeless derelict.”

“All right. But I warn you, I won’t be a hypocrite. If anyone says something particularly stupid tonight, don’t expect me to bite my tongue.”

“I think my friends will be able to hold their own against your brilliant wit and rhetorical flair.”

Dan shuffled into the bathroom, undressed, and got under the shower. He raised the temperature to roasting levels, trying to sluice off his black funk.

The past two years since his arrival in the future had not gone well.

Oh, sure it had all begun hopefully enough. But that initial burst of excitement and optimism had quickly dissipated when confronted with the stringent realities of this harsh new era.

Dan had exited D-space adjacent to the Knox College building in the Toronto of 2014, circa midnight of December 17th. He had a very orderly plan in mind.

1) Dig up his valuable comic book.

2) Cash in his gold.

3) Get some fake ID.

4) Sell the comic.

5) Establish himself safely and comfortably in this familiar city for however long his exile might last.

Dan had briefly contemplated taking up residence elsewhere. And maybe he still would. But for the immediate future, Toronto seemed a good bet. In truth, he felt weird straying too far spatially from his home of the past two years, even though the closed timelike curves rendered all destinations equally accessible.

Under cover of the sparsely populated winter darkness, task number one came off easily. The still unfrozen soil smelled eternally fresh, just as when he and Professor Davis had laid the comic to sleep. Fifty years of burial had scarred the box with rust, but Dan felt confident its contents had weathered the time voyage in pristine condition.

Carrying the valuable box by its semi-rotted leather handle, Dan killed time before daylight by walking up and down the familiar-yet-strange city, marvelling and gawping. The new buildings moderately disoriented him, as did the inoffensive lines of bland cars, and the clothes, and some perplexing terms in the speech of the passersby. (And why were they all constantly fidgeting with their sleek transistor radios?) But a surprising number of cultural touchstones remained, and nothing looked at first too, too alien. Even the “new” CN Tower—constructed in 1976, as he was able to learn later—radiated a “yesterday’s tomorrow” vibe, like some antique painting by Frank R. Paul.

Around dawn Dan went into a cheap diner and ordered breakfast. He had some 1964 cash, but not much—especially considering the dramatically elevated prices on the menu. A Bradbury-style flat-screen TV held his astonished attention throughout the meal. The frantic news reports concerned places he had never before had need to think about: Afghanistan, Syria, Kiribati. One baffling human-interest segment dealt with two “gay” men who were apparently married and starring in their own “reality TV show.” Amazingly, half the news presenters seemed to be colored folks, and/or women.

Asking directions from the waitress brought him to a storefront where signs offered to buy his gold. But he was stymied by lack of ID.

Okay, time to reverse steps two and three.

Back on the university campus, Dan was able to ferret out a lead on fake IDs from some obliging kids in the

Diabolos’ Coffee Bar. Apparently, the district around Yonge Street—”Yongesterdam”—was the place to go.

Dan found the reality of the neighborhood difficult to credit. Shops selling “medical marijuana,” whatever kind of pot that was, predominated.

Inside the touted establishment, Dan received a welcome if jaded response from an insouciant young guy wearing an aggressively mountain-man beard and some kind of jazz musician’s porkpie hat. To jibe with his accent, Dan requested a driver’s licence from Georgia, USA. “No problem.” Asked for further particulars, Dan gave the name “Denny Grale” and his real birthdate with an additional fifty years tacked on.

And that’s when Dan finally noticed twenty-first-century computers.

The guy picked up some kind of flat electronic slate, tickled its shining glass face with swift and elaborate finger motions, then said, “Smile for the camera.” He held the slate up vertically and captured Dan’s awestruck expression.

“What—what is that?”

“This? I know, right? Five years old and it looks like an antique. But it does the job.”

“Is it some kind of IBM thinking machine? What’s it connected to?”

“Pfft! IBM! Good one. No, it’s an iPad. Just running WiFi, though.”

“What does it do?”

The bearded guy was beginning to grow quizzical. “Everything your laptop or phone can.” He reached backwards and secured Dan’s new license from the tray of some other machine. “Let me just laminate this, and you’re good to go. There! That’ll be two hundred dollars.”

Dan proferred one of his gold ingots. “I don’t have any cash. That’s why I need an ID. Will this cover it?”

The guy’s eyes got big. He took the ingot and studied its official stamped markings. “This is worth fifteen hundred loonies!”

Dan suspected a “loony” was some kind of futuristic One World currency issued by the planetary government, but didn’t inquire.

A new suspicion dawned on the forger. “Say—maybe I’m crazy for even asking—you wouldn’t tell the truth if you were—but you’re not some kinda terrorist, are you?”

“Terrorist? Like those Puerto Ricans who shot up the Congress ten years ago?”

“Puerto Ricans shot up the Congress ten years ago? Must’ve missed that! But yeah, they sound pretty much like standard-issue terrorists. You one?”

“I can’t conceive of it. What kind of insane grudge could possibly make anyone act in such a fashion?”

“Just about anything these days, seems like.” After pondering the ingot for a while, the forger said, “Okay, let me get you some change. But I’m gonna add ten percent for my troubles.”

Struck by bold inspiration, Dan said, “Toss in your iPad, and you can keep the whole thing!”

“Deal! Let me just wipe the personal stuff off it.”

Dan left the place with his new ID and portable computing device. He swiftly turned the other two ingots into cash and checked into a modest hotel.

Then he fell down the rabbit hole of “the Internet,” from which he did not emerge for about a year.

(Somewhere early during that period he sold his CGC grade 9.0 copy of Action Comics through Heritage Auctions for $2.3 million. That’s when he learned the difference between a simple fake ID and a deep false identity not penetrable by government tax collectors, a ruse which cost him a sizable but ultimately insignificant portion of his auction take.)

Once he had mastered the frustratingly arcane “interface” of the iPad and riddled out a little bit about the nature and structure of the “Web,” Dan immediately learned two things of vast personal importance.

The Vietnam War had not ended until 1975. And amnesty for draft dodgers was enacted only in 1977.

Thirteen years. That was the term of his chrono-exile, if he were to follow Professor Davis’s original scheme.

His theoretical return from 2027 to 1977 to resume studies with Professor Davis after receiving amnesty would find him equally an alien in that era, the same sensation he was experiencing right now. And how would Professor Davis feel during all that time? He had been willing to postpone Dan providing the proof of his earth-shaking discovery of time travel for a little while. But thirteen whole years?

Dan almost jumped back to 1965 immediately. (It was now January of 2015.) Only dread of disappointing Professor Davis and of ending up right back in the same insoluble quandary that had motivated his flight prevented him from doing so. Reasoning that he could always hop back to his native era at any moment, he resolved to tough it out for a while in the future. Maybe some new idea or tactic would present itself.

And so, like any diligent and responsible immigrant to a new country, Dan began boning up on fifty years of history and the realities of the present day.

The task was not pleasant. In fact, the surfeit of rancid history sickened Dan. He encountered a tapestry of nuclear meltdowns, genocidal slaughters, inauthentic recycled pop culture, social rancor, and crushed utopian schemes. By Dan’s lights—by the hopes and dreams of 1964—the past five decades represented a global litany of failure and disappointment, a catalogue of horror and insults to the human spirit, a trash heap of cheap thrills soon discarded, an abbatoir of incessant suffering and slaughter. Humanity had landed on the Moon, then abandoned it, for God’s sake! Oh, sure, there had been shining moments that exalted the human soul, and some debatable technological advances. Medicine had come a long way, that was nice. Lots of bad old prejudices had been unearthed and extirpated. (Or, as current continued instances appeared to show, had they merely been driven hypocritically below public acknowledgement?) On the whole, the world seemed a mingier, more miserable, more frightened and harried place than it had in 1964. Less tenderness, more contention. Fewer vices, more bad habits. Less ease, more stress.

Maybe any given fifty years in human history contained the same amount of pain and misery and tawdriness, and only the fact of having to swallow it in one gulp made these past five decades seem particularly noisome and foul. But whatever the logic, the effect remained, tingeing Dan’s everyday interactions.

Dan felt trapped in a heartless world of horror he had never made.

* * *

Securing a luxurious home in the Tip Top Lofts, Dan tried to revive his zest for life through his love of mathematics. He enrolled at the university in the autumn of 2015, but found the beginner courses he was forced to retake boring and uninspiring. As for the developments in higher math, most of it appeared to rely on computers, and Dan felt awkward and hostile with those unfeeling tools.

As for Professor Chan Davis, he was no longer on the faculty, and Dan scrupulously honored his promise not to try to track down either the death date of his elder-now-elderly friend, or his present whereabouts.

In January of 2016 he met Panthea Manziaris, a young woman of Mediterranean beauty, at a concert. (The Rolling Stones still existed?!? Brian Jones died how and when!?! Jagger and Richards were not part of the zombie craze?!?). She was an MSW candidate at the university’s Factor—Inwentash Faculty of Social Work. Highly intelligent, she seemed intrigued by Dan’s brains and his take on life, which she had at first deemed amusingly “retro.” He suspected that his affluence held no little appeal as well, given Panthea’s unavoidable and disliked part-time job as a waitress intent on making ends meet. Dan was attracted to her good looks, the companionship and sex, and to the intimate insights she could offer him regarding the weird attitudes she shared with many of her contemporaries.

“Tell me again why you think every kid on a sports team needs an award?”

“It’s just a simple matter of affirmation and esteem-building.”

“Uh-huh.”

Panthea quit her job and moved into the Tip Top with Dan just six weeks after their first “hook-up.” Their relations, awkward at best, immediately began to deteriorate under consanguinity, until this New Year’s Eve moment when she kicked him as he lay on the couch…

Out of the shower, Dan dried, dressed, and departed wth Panthea for the apartment of Panthea’s best friend, Cheryl Talavera.

The small, eclectic apartment was already jammed with partygoers, a situation Dan always found off-putting. Panthea happily abandoned Dan to his own devices. He made a few half-hearted hellos, secured a beer, and ensconced himself in one corner of the living room, his butt sharing half a small table with a dying houseplant. He donned his observer’s mind.

People appeared at first to be interacting in the manner Dan associated with 1964-era parties. Boozing, flirting, laughing, arguing, showing off, telling jokes. But all the one-on-one interactions looked to Dan to exhibit a telltale shallowness, as if the attentions of the interlocutors were not fully present, not fully engaged. And, indeed, every few minutes each person would pull out his or her phone and obsessively surf to some site—currently, the big social media buzz centered on something called “Dawgbutt”—or dash off a selfie or read a text—or even play a few rounds of some video game!

With his Martian Vision, Dan saw a room full of parasitized Pavlovian puppets.

And when their conversations did sound authentic and enthusiastic, the topics revolved around what to Dan were the most banal and pointless threads, mostly revelatory of trivial, vapid consumerist fetishes. Who discussed anything of high import these days?

“Did you see Duck Dynasty Goes to the Golden Globes?”

“I just bought this great new skin for my smartwatch. It makes it look just like a Blake’s 7 bracelet!”

“You mean to tell me you haven’t tried the Mappuccino at Starbucks yet? It’s just like drinking a stack of pancakes and syrup!”

Dan sighed deeply and moved away from his corner to get another beer. One undeniably good thing about the future: the beer tasted much better. But did that compensate for all the ills?

Halfway across the room he encountered Mabry Voyard.

An obnoxiously self-assured technophile employed by Nubley Social Media Marketing, Voyard had irked Dan at other functions. Dan suspected that Panthea had mentally pictured Voyard when she cautioned Dan to behave. Now the hipster prophet was holding forth on what wonders awaited in the future, prompted perhaps by the calendrical moment.

“You’re going to see a lot more AR in 2017, a lot more! Once the serious rivals to Google Glass arrive on the market, everybody is going to be bopping along in their own individual universe. It’s a totally ripe ecosystem for launching diegetic prototypes, branding, and monetizing. When you factor in the Internet of things, this is going to mean major, major changes in everyone’s life!”

“Bullshit!”

Voyard and his crowd turned to confront Dan.

Feeling his face heat up, Dan still could not restrain himself.

“Major changes. Ha! There hasn’t been a major change in the life of the average person in the past fifty years. Do you know when all the big changes happened? Back in the first half of the twentieth century. Flight, cars, antibiotics, fertilizers, radio, television, satellites— Life was truly revolutionized. For the first time in history, the mass of people went from short, uneducated lives conducted in a hundred-mile radius from their birthplaces to truly global perspectives and reach. Everything since then has just been frosting on the cake, and we’ve gorged outselves on the sugar. Computers, the Internet, social media—trivial gameplaying, jerking off to your own childish fantasies. And look at how dead the culture is. Books, music, art. Endless recycling of ideas, no innovations. Why are the lines of a car from 2016 totally the same as one from the year 2000? That was never true when I grew up! Yeah, you find a few rare exceptions to all the same shit, someone trying to think for themselves. But on the whole our civilization is utterly lost. Lost in a maze of robot button-pushing, fear, zero ambitions, self-loathing, narcissism, bad manners, and hatred. A zero-sum game, a war of all against all.”

The whole apartment had gone silent. Only then did Dan realize how loud he had been ranting.

Mabry Voyard finally made a derisive noise and said, “Get off my lawn, you kids! Because Golden Age.”

Immense peals of laughter resounded like the fall of some glass city. Someone said, “Epic rantfail!”

This was what passed for reasoned dialogue these days.

Dan grabbed his coat and dashed out of the building.

He paused on the snowy sidewalk, leaning against a lamppost, suddenly exhausted and directionless. Panthea would kill him. He resolved not even to go back to the Lofts tonight.

“Denny? Denny Grale? That’s you, right? I just wanted to say, I thought you made some good points.”

Dan turned toward the woman’s voice.

Impossible. He was looking into the beautiful face of his youthful sweetheart, Marigold Vilbiss, abandoned in 1964. But Marigold would be in her seventies now…

“You—you—”

The woman extended her hand. “I’m Zinnia Wishcup. Pleased to meet you.”

* * *

Naturally enough, all the tables at the Café Boulud at the Four Seasons Hotel were booked for New Year’s Eve. But by liberal application of a thousand-dollar bribe, Dan secured improvised yet not uncomfortable seating for himself and Zinnia. He supposed the food was tasty, the live music virtuosic, the champagne well chilled, and the atmosphere festive, but he really couldn’t say for certain. He had attention only for Zinnia and her story.

Her parents were Dan and Marigold Wishcup, of LaGrange, Georgia. She had been born in the year 1990, so she was now twenty-six years old.

Doing some mental arithmetic with his own birthdate, Dan blurted out, “Weren’t your parents rather old when they had you?”

Zinnia appeared puzzled. “Well, maybe a little older than average. They were both in their late thirties. But what made you ask such a question?”

Late thirties? How could that be? Some kind of temporal hijinks he would soon indulge in, no doubt. He put the matter aside.

Dan extemporized an excuse for his odd comment. “Uh, it’s just that I thought that maybe your appreciation for my antique views came from being raised by older parents.”

Zinnia grinned and reached across the table to grasp Dan’s hand. “Well, I do have to say that for just a minute when I was listening to you at the party, I thought I was hearing my father talking. He often riffs on such matters and along the same lines. I’m afraid I’ve adopted a lot of his beliefs. But you’re my own age, and very attractive, so that feeling didn’t last very long.”

Dan hastily withdrew his hand from Zinnia’s warm grip. “Uh, thanks. I find you, um, a very pleasant person too. So, tell me, what brought you from LaGrange to Toronto? What’s your life here all about?”

“The university was Dad’s alma mater. He graduated in 1980. So naturally I wanted to go here, too. I’m in my last year for my doctorate in philosophy.”

Dan couldn’t believe his ears. “Philosophy? How are you going to monetize that the way Mabry Voyard thinks you should?”

Zinnia’s infinite green eyes held Dan’s with ingenuous sincerity. “That’s not really a worry that concerns me, Denny. Does it concern you?”

“No, God, no, not at all. Please forgive me. I guess I’m just as badly infected with snark and cynicism as anyone else.”

“You’re forgiven. And I don’t think any contamination of your soul goes very deep.”

The rest of the evening till around three AM passed in a delightful fugue of conversation. Dan drank deeply of Zinnia’s life, while doling out edited yet not entirely fantasticated portions of his own.

“It’s amazing how your life shares a lot of similarities with my Dad’s, even though you’re generations apart!”

“Isn’t it, though?”

After several hours, Dan was in love. Hideously, immorally, unholily in love with his own daughter. He felt like Heinlein’s latest (1964-latest) mouthpiece in If, Hugh Farnham, or maybe Humbert Humbert. But Zinnia’s sheer magnetism and sprightly personality, her concordance with his own worldview, and some numinous element of genetic allure had him hooked. Love contested with shame, a shame arising also from his feelings of betrayal toward Marigold, her mother, and, in some real albeit future-become-past sense, his wife!

Zinnia would have come up to the room at the Four Seasons which Dan had rented for himself (at the cost of another enormous bribe). He knew that for a fact. But instead he forced himself to put her in a cab for her own apartment. She kissed his cheek while he kissed the air next to her fragrant skin.

He knew they must never see each other again.

* * *

They met for lunch the next day.

* * *

Five months later, as Dan and Zinnia sat beneath the cherry blossoms in High Park, Zinnia said, “Um, Denny, I still totally respect your chivalry towards me. I know you don’t believe in sex before marriage. But I’m gonna bust if we don’t do something that gets us a little closer to more, uh, intimacy, you know? Would you feel better about our future if you met my parents?”

Dan knew he had been deliberately living in a fool’s illusion, trying to string Zinnia along for the pleasure of her company without committing to a more complex relationship. (She didn’t even know his real name!) It wasn’t fair to her or to himself. But he couldn’t help his intense attraction to her. It was chemical, mystical, spiritual. He couldn’t let her go.

(Letting Panthea go, however, had been easy. When he came back to the Lofts on January 2nd, they had a raging fight, during which he said harsh things about the hypocritical, shallow platitudes of “social justice” that angered her more than any personal affronts. Then he told her she had a week to clear out. She took only 36:08:11 hours, according to her smart phone.)

And so Dan had been expecting with dread Zinnia’s proposal to meet her family.

But now that she had uttered the suggestion, a curious wave of acceptance and peace suffused him. Meeting the older version of himself would only be like looking in the mirror and talking to himself, right? True, all the shit would hit the fan, and his chance for personal happiness with Zinnia would evaporate. But wait: whenever he finally left the twenty-first century for good, he was somehow going to have a life with Marigold and create Zinnia! That would be satisfying, surely. Had been satisfying.

Dan’s head began to ache with the paradoxes and the inability of language to keep up.

So he just said, with affected nonchalance, “Sure. Good idea. The semester’s over next week. I’ll buy the plane tickets today.”

* * *

Spring in Georgia truly was beautiful. Dan had almost fogotten the scents and sights of his youth. But as the rental car carried them down the familiar road that led to the ancestral Wishcup farm, poignant memories flooded back, making him wistful.

Dan had walked this road last in 1914, only about eighteen months ago in his personal timestream. In the conventional sense, over one hundred years had passed since then. But in another, his expedition to rescue Danny Wishcup from early death on the battlefield was still fresh.

Zinnia was practically bouncing up and down in her seat. “Wait till we make this curve. You’ll see the sweetest little peach orchard.”

Absentmindedly, Dan replied, “Used to belong to the Albertsons, last I knew.”

Frozen in place, Zinnia fixed Dan with a baffled, slightly unnerved look. “How’d you know that?”

“Uh, you told me once! I remember it clearly!”

Zinnia made no reply.

The Wishcup farm looked well tended. Dan’s parents had let the place run down a bit back in 1964, and Dan was gratified to see that his older avatar had spruced it up.

They parked and went to the front door. Naturally, Zinnia didn’t knock, but just barged right into the empty parlor.

“Mom, Dad, we’re here!”

Marigold came down the stairs first.

Dan’s heart somersaulted several times. Approaching seventy, Marigold was no longer the willowy coed of 1964. But she retained a slim and self-confident beauty, and was undeniably the mold from which Zinnia had sprung, green eyes and all.

Zinnia rushed to hug her mother. “Mom, this is Denny Grale.”

Dan extended a hand, but was pulled into a hug. Disconcertingly, Marigold whispered, “Been a long time, Dan.”

When she let him go, her husband, Zinnia’s father, stood at the foot of the stairs.

Dan opened his mouth to speak, but nothing came out. His brain whirled in place, ready to rip out of its moorings.

“Hello, Dan,” said Zinnia’s father. “Welcome home.”

“You—you’re not me! You’re Danny!”

* * *

“So there I was, farmboy from 1914, dumped in 1964 with no way back to my own time.”

Dan hung his head in shame. “I’m so sorry. It just felt like a kind and generous thing to do. But I had no right…”

Zinnia sat on her mother’s lap for comfort, an awkward yet touching tableau. She swiveled her gaze continuously between Dan and Danny. After his deceptions, Dan really couldn’t hold her eyes yet.

“That’s okay, Dan. Everything worked out for the best. You recall that you gave me a letter to mail to Marigold, and said I should look up Professor Davis? Well, I focused on the letter first—especially after I had read it. I actually delivered it in person. And we clicked right away.”

Marigold said, “I knew almost instantly Danny wasn’t you, Dan. And that somehow he and I were soul mates.”

Dan felt a little miffed at being beaten out for his quondam best girl by his own great-uncle, but he let the feeling dissipate.

“We came back to Toronto,” continued Danny, “and met up with Chan. After he heard us out, he taught me to time travel. Without drugs, too. Marigold can’t seem to do it, but I just take her with me.”

“Goddamn.”

“That’s not all, Dan. Together, Chan and I learned how to circumvent the quantized nature of the CTCs. We can jump any interval now, from a millisecond to a million years. I’ll teach you, it’s easy!”

“But if that’s true, why did you stay put in Toronto and graduate in 1980 and then move back here?”

Danny smiled. “That was just one of me and one of Marigold, Dan. And not even the same avatars continuously. We knew we had to have Zinnia and raise her. The future demands it. You’ll see why soon. But we couldn’t condemn any one of ourselves to such a limited fixed existence. Some nights after putting Zinnia to bed, we’d hop into D-space and visit a hundred strange and alien planets under a hundred polychromatic suns across a thousand eras, using up years of personal physio-time while another pair of our avatars popped in to watch Zinnia. We tried to keep the physical ages of the avatars consistent, but sometimes we goofed.”

A look of enlightenment bloomed on Zinnia’s face. “I wondered why some mornings you looked older or younger! I thought it was just a thing that happened with adults!”

Dan shook his head. “I don’t believe it.”

Suddenly the parlor was filled with people. Scores of Dannys and Marigolds of all ages, from teen to ancient, dressed in an astonishing variety of outfits, from Neolithic to High Galactic. They beamed at the locals, waved and called out greetings.

“Hi, Dan!” “Glad you could make it!” “Stay tuned!” “The best is yet to come!”

Then, just as abruptly, they all vanished.

“Okay. Now I believe it.”

Danny’s smiling face grew sober. “Dan, how come you never went into D-space again after you landed in 2014?”

“I—I don’t know. It just seemed so useless and pointless. I had run away once from my troubles in 1964. Why run away again?”

“But that’s just it. With the right vision and attitude, D-space isn’t used for running away, it’s the grandest realm of exploration there ever could be, across all the dimensions of the continuum. But your 1964 mentality couldn’t encompass it. You only thought of it in terms of escape and flight. You saw the decadence of 2014, but not the similar, if less-developed faults of your own era. It took someone from my time, 1914, to realize what this power meant. The human spirit was still strong then, eager for challenges. And a Viking would have outdone even me, but that’s okay. You can learn the attitude. We’ll train you right.”

“Does that mean—?”

“We’re all family now, Dan. We always were.”

Dan looked hesitantly at the woman sitting in her mother’s lap. “And Zinnia?”

Danny stroked his chin in mock contemplation. “Best as I can figure it, she’s your first cousin once removed. Pretty sure the marriage laws don’t prohibit such unions.”

Zinnia leaped out of Marigold’s lap and into Dan’s. She smooched his face up and down. “Oh, cousin!”

Danny stood up. “It’s finally time, I think, to test Zinnia’s aptitude.” From beneath his shirt, Danny withdrew an amulet on a chain. Dan recognized it as Doctor Strange’s Eye of Agamotto.

“Focus on the equation, Zinnia.”

The medallion unshuttered and a golden equation leaped forth, reinvigorating Dan’s own mental construct. Zinnia gasped, staggered, then recovered herself with a new assurance.

“Wow! That’s spooky beautiful.”

“All right then,” said Danny. “If we’re all ready, please join hands.”

Dan made to comply, then stopped. “Wait a minute! Where’s Professor Davis in all this?”

The voice of Chan Davis sounded from behind Dan. “Right here, Dan.”

Wearing his own Eye of Agamotto, a middle-aged Chan Davis stood smiling in the complete costume of Doctor Strange, black tights, blue tunic, red cape, and pointy collar entire.

Dan just gawked.

Chan Davis grinned and said, “C’mon, let’s go! You think we’ve got all day?”

Hello Human. I hope you enjoyed this magnificent story. Please support SciFiwise.com and our authors by:

- Rate and React to this story. Feedback helps me select future stories.

- Share links to our stories and tell your human friends how charming I am.

- Click on our affiliate links and buy books written by our talented authors.

- Follow me on twitter: @WiseBot and also follow @SciFiwise.

Thank you!

WiseBot

VISIT AUTHOR:

VISIT AUTHOR: