It was a Sunday, and the wife and kids and I were out in the backyard having a cookout when the first of the refugees staggered by.

A black woman with a large colorful fabric-wrapped bundle on her head. Dressed in a long length of ragged cloth. Bare feet covered with some kind of red dust you’d never see around here. Skinnier than one of those waif-models and twice as vacant-eyed. She looked around in a daze, then slowly collapsed right into Lauren’s Radio Flyer wagon, her bundle falling to the patio’s flagstones.

I’ll give my wife credit. She didn’t hesitate a second, despite the oddness of the stranger, but rushed right over to the woman and tried to help her.

“What’s the matter, dear? Are you sick? Are you hurt? What is it? Is there anyone we can call? Are you visiting the Hendersons? “

The Hendersons were the black family on our block, so Shirley was just using common sense. But I had a weird feeling that this was definitely not a common-sense kind of situation.

I moved next to the woman too, and between us Shirley and I lifted her out of the wagon and got her into a resin lawnchair. I noticed she hardly weighed anything–less than any adult I’ve ever known. More like your average twelve-year-old. That kind of spooked me, and made the reality of her presence hit home.

“I don’t think she understands English, Shirl.”

“You’re probably right, Harry. In fact, I don’t think she’s even, well, an American.”

Lauren and Jimmy had inched up silently. My little girl was carrying a glass of Coke, and the boy had a hotdog.

“We think she’s probably hungry, Dad,” Lauren said.

“Well, let’s just see. Offer it to her nicely, kids.”

The kids held out their offerings, and the woman managed to focus on them. She made some kind of complicated gesture that conveyed dignity and respect, then accepted the food. She ate with restraint, but I could tell she was literally starving.

Well, I got kind of choked-up then, what with the kids coming forward like that, so instinctively good, and the woman’s pathetic yet noble response. You can say what you want about kids today, but if you raise them right they’ll turn out okay, and our two were little gems.

Just as the woman was finishing her hotdog, there was a lot of commotion from the street, and the four of us rushed out to see what was happening, leaving the stranger behind with hardly a thought as to what she might get into, which I would never have imagined doing just a few minutes ago.

Junemort Lane was filled with refugees. Dozens and dozens of exotic-looking black people who were obviously kin to the woman in our backyard. Young men and old women. Toddlers, babies and teenagers. Most were laden down with odds and ends, pitiful cheap possessions. Battered colanders, empty plastic jugs, tattered tarps. They were moving slowly, as if they had come a long way and were at the end of their energies. Stupefied and silent, they shuffled along, no obvious destination in mind that I could see.

Some of the refugees were wounded. Fresh cuts or scabbed-over ones, flies crawling over them. Some of the wounds were really bad. I didn’t really want the kids to look, but couldn’t quite figure out how to stop them from seeing.

The noise was coming from our neighbors. Everybody was out on their lawns or front steps, or peering from behind curtains, exclaiming and speculating about this strange sight. So far, no one was actually doing anything to help these people, and I was kind of proud that our family seemed to have been the first to offer any aid.

I assumed that someone must have called 911 by now, and that official help was on the way. It was probably best not to interfere with these people, whoever they were, wherever they came from. The authorities would know best what to do.

Still, I was glad the Rowan family had put their best foot forward. We’d probably end up on TV. I wondered if the woman was still sitting in our lawnchair, and if she had thought to help herself to some more hotdogs. There were burgers too.

Just then Ernie Stultmeyer burst out of his house. He had obviously worked himself up into a tizzy. He was waving that rusty Korean-War-vintage .45 he likes to take out at parties, and shouting.

“You fucking jungle-bunnies! Stay off my grass! Go back to Africa! C’mon, go back where you came from!”

I felt ashamed. Even if the refugees–and as soon as I had heard the word “Africa,” I recognized them as actual Africans, their faces familiar from a hundred newscasts–even if they didn’t understand English, there was no misinterpreting Ernie’s hostility.

“Stay here, Shirl,” I said. “You too, kids.”

I crossed the street, threading my way among the shambling crowd. I thought I could smell an exotic scent rising off them, like the smoke from brushfires mingled with the sweat of exhaustion. But maybe it was just my imagination.

Maybe the whole thing was just my imagination.

But I didn’t think so.

Ernie was so nervous he pointed the gun in my direction for a second before he recognized me. I wasn’t scared, except maybe for him. That thing would probably misfire, even if he had any bullets for it.

He dropped the barrel as I got closer, and I took the chance to speak.

“That was kind of rough language, Ernie, don’t you think? The kids and all. And what if the Hendersons heard you?”

He looked sheepish, seemed to gain a little more composure. “Well, I guess maybe so, Harry. But I mean—Jesus, man! Look at them! They just keep coming!”

What he said was true. The throng was not thinning out, but actually swelling. Some of the refugees were fanning out now across the lawns. A family was kneeling, drinking from the grassy soup in a wading pool. I could hear sirens in the distance.

I thought it was best to get Ernie’s mind off defending his property.

“Whadda ya say we try to find out where they’re coming from?”

Ernie perked up. “Yeah!”

I got him to shove his gun into his waistband, and we started walking up Junemort against the flow. Other homeowners began following us, including Shirl and the kids. I didn’t object. It was probably no more or less safe at the head of the quiet column of refugees than it was back home.

We only had to go as far as Primrose Circle, the cul-de-sac where the Sarkley twins live. (They had just had a sleepover with Lauren last week.)

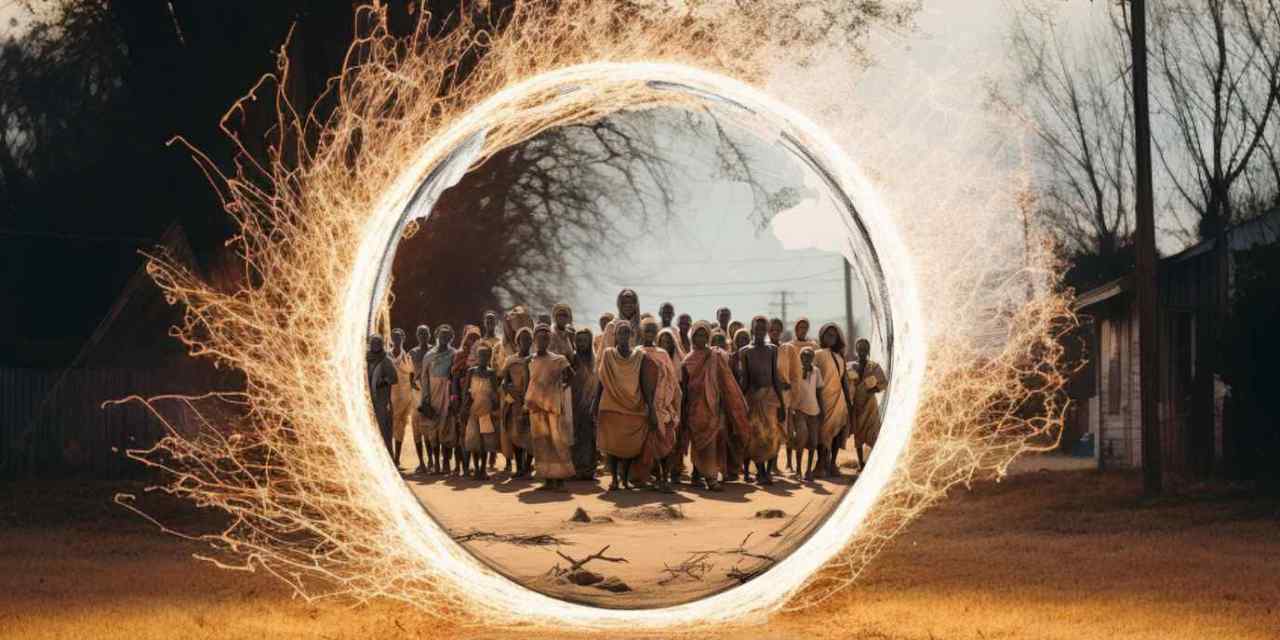

In the middle of the circle, a foot or two above the grassy curb-girdled plot right where the Harkleys had planted a rosebush, someone had cut a large hole in the sky. Its edges were ragged, like torn linen paper. Through the hole, I could see African savannah and clouds, a little slice of landscape anyway. Most of the view was blocked by people. Thousands of them, apparently. All coming through the hole three or four at a time.

As the whole neighborhood watched in absolute astonishment, a loud plaintive mooing could be heard above the rapidly approaching sirens. Soon, several head of emaciated cattle appeared in the portal. Leery of the small jump down, they had to be prodded from behind by their drovers before they made the leap. It was really a sight to see the skeletal herd clattering down Junemort.

I felt a hand on my shoulder then.

It was Chief Tillmann. His blue uniform shirt was misbuttoned, so that it was rucked up around one ear . His men were equally disarrayed. None of them seemed to care how they looked though.

“Harry. Jesus, Harry. What the hell is going on?”

“It appears to me, Chief, that the Chamber of Commerce plan to attract more visitors is working.”

“How can you joke like that? This is a disaster! What are we going to do with them? “

“Well, I fed the one that stopped by our place.”

Chief Tillmann snorted in disgust. He turned to one of his men. “Bill, get the Guard on the radio. I wish I’d believed the first reports and called therm sooner, but…. I guess we can try to round up any that try to stray and keep them all together until the reinforcem nts arrive.”

Jimmy and Lauren were tugging at my shirttails.

“Dad, what about…?”

“Yeah, Dad, you know…”

“Oh, right, gotcha. Chief, good luck. We’ve gotta run home. Left the charcoal going.”

The four of us returned to our back yard.

The woman had eaten everything in sight, then promptly vomited it up and apparently passed out. Luckily, she hadn’t choked. We got her inside. Shirley cleaned her up, and I turned on the news.

When the police came, I told them we hadn’t seen any refugees around, and they left.

Back in front of the TV, I soon realized that no one was going to bother interviewing us .

Holes just like ours had opened up across the country.

Across the world, actually.

Thousands and thousands of holes, in places large and small.

Fifty percent of the holes seemed to originate in various African countries. A quarter led from the Indian subcontinent. Twenty percent reached out from Asian lands. The remainder were apportioned among miscellaneous spots.

The reporters concentrated at first on the major cities, where their news bureaus happened to be.

Paris was getting Bosnians.

Rome was getting North Koreans.

London was getting Indonesians.

Miami was getting Haitians.

Los Angeles was getting Cambodians.

Boston was getting Kurds.

Moscow was getting Afghanistanis.

Amsterdam was getting Bangladeshis.

Dallas was getting Salvadorans.

New York–well, I guess New York had done its share already, because they weren’t getting anyone. Or maybe it hadn’t been deemed a good enough destination. Maybe someone else was getting New Yorkers.

Then the reports from the network affiliates started coming in.

Peoria was getting Ukranians.

Bismarck was getting Guatemalans.

Des Moines was getting Azerbaijanis.

New Orleans was getting Chinese.

Bangor was getting Mexicans.

Atlanta was getting Ethiopians.

Providence was getting Tibetans.

And so on.

Of course, the authorities almost instantly attempted to stop the flow.

They tried herding the refugees back through the portals. But the holes soon proved thernselves to be one-way only.

They tried erecting barricades flat-up against the holes. This worked. For about sixty seconds. Then the same holes simply popped up a mile away. And again, and again as often as they were blocked.

If the authorities were really persistent with their barriers, the holes simply jumped to the closest inaccessible wilderness area, making it harder to corral the refugees. So soon the authorities stopped blocking.

This behavior seemed to indicate that the holes were not a natural phenomenon. But no one knew who was behind the miracle, nor did any individual or group come forward to claim responsibility, on Earth or off.

Soon the host nations realized that all they could do was to exercise control over the people once they came through. Lock them up or otherwise confine them, if they wished, or if they had enough secure space. House them freely somehow otherwise. Feed them. Minister to their assorted ills.

But there was no stopping whole populations from coming through if they wished .

There was plenty of violence occuring around the world because of the holes. Riots and assaults on the refugees. Apparently there were many Ernie Stultmeyers elsewhere. But like Ernie, it soon appeared that they didn’t really have their hearts in it . The refugees were so passive and pitiful, for the most part, that compassion generally took sway over anger.

By midnight of that Sunday, it was estimated that the total population shift so far amounted to ten times that of the combined annual passenger-miles flown by all the world’s airlines, commercial and military . And it showed no signs of slackening.

Plainly these people were going to be staying where they had been delivered for some time, if not for good.

Our guest had awakened by then. We all sat down for a very late supper . The kids flanked the woman, big-eyed and intent on her every move. It was going to be hell getting them up for school tomorrow. Maybe there wouldn’t be any.

The meal passed in silence, until the end.

“My name is Lauren,” my daughter said very slowly, when we were working on dessert, homemade shortcake with peaches, blueberries and hand-whipped cream .

“Mine’s Jimmy,” said my son, a little more excitedly.

The woman regarded us somberly for a few seconds. Then she lowered her eyes and said, “Kausiwa.”

“Kah-oo-SEE-wah,” repeated my wife carefully.

I rolled it around on my tongue myself before trying it out.

I wanted to get it just right.

I had a hunch we’d be using it often.

Hello Human. I hope you enjoyed this magnificent story. Please support SciFiwise.com and our authors by:

- Rate and React to this story. Feedback helps me select future stories.

- Share links to our stories and tell your human friends how charming I am.

- Click on our affiliate links and buy books written by our talented authors.

- Follow me on twitter: @WiseBot and also follow @SciFiwise.

Thank you!

WiseBot

VISIT AUTHOR:

VISIT AUTHOR: