Allen Dodson was sitting in seventh-grade math class, staring at the back of Peggy Corcoran’s head, when he had the insight that changed the world. First his own world and then, eventually, like dominos toppling in predestined rhythm, everybody else’s, until nothing could ever be the same again. Although we didn’t, of course, know that back then.

The source of the insight was Peggy Corcoran. Allen had sat behind her since third grade (Anderson, Blake, Corcoran, Dodson, DuQuesne . . .) and never thought her remarkable. Nor was she. It was 1982 and Peggy wore a David Bowie t-shirt and straggly brown braids. But now, staring at the back of her mousy hair, Allen suddenly realized that Peggy’s head must be a sloppy mess of skittering thoughts and contradictory feelings and half-buried longings—just as his was. Nobody was what they seemed to be!

The realization actually made his stomach roil. In books and movies, characters had one thought at a time: “Elementary, my dear Watson.” “An offer he couldn’t refuse.” “Beam me up, Scotty!” But Allen’s own mind, when he tried to watch it, was different. Ten more minutes of class I’m hungry gotta pee the answer is x+6 you moron what would it be like to kiss Linda Wilson M*A*S*H on tonight really gotta pee locker stuck today Linda eight more minutes do the first sixteen problems baseball after school—

No. Not even close. He would have to include his mind watching those thoughts and then his thoughts about the watching thoughts and then—

And Peggy Corcoran was doing all that, too.

And Linda Wilson.

And Jeff Gallagher.

And Mr. Henderson, standing at the front of math class.

And everyone in the world, all with thoughts zooming through their heads fast as electricity, thoughts bumping into each other and fighting each other and blotting each other out, a mess inside every mind on the whole Earth, nothing sensible or orderly or predictable . . . Why, right this minute Mr. Henderson could be thinking terrible things even as he assigned the first sixteen problems on page 145, terrible things about Allen even, or Mr. Henderson could be thinking about his lunch or hating teaching or planning a murder . . . You could never know. No one was settled or simple, nothing could be counted on . . .

Allen had to be carried, screaming, from math class.

***

I didn’t learn any of this until decades later, of course. Allen and I weren’t friends, even though we sat across the aisle from each other (Edwards, Farr, Fitzgerald, Gallagher . . .). And after the screaming fit, I thought he was just as weird as everyone else thought. I never taunted Allen like some of the boys, or laughed at him like the girls, and a part of me was actually interested in the strange things he sometimes said in class, always looking as if he had no idea how peculiar he sounded. But I wasn’t strong enough to go against the herd and make friends with such a loser.

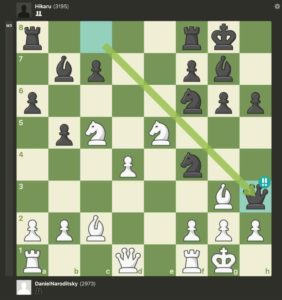

The summer before Allen went off to Harvard, we did become—if not friends—then chess companions. “You play rotten, Jeff,” Allen said to me with his characteristic, oblivious candor, “but nobody else plays at all.” So two or three times a week we sat on his parents’ screened porch and battled it out on the chessboard. I never won. Time after time I slammed out of the house in frustration and shame, vowing not to return. After all, unlike wimpy Allen, I had better things to do with my time: girls, cars, James Bond movies. But I always went back.

Allen’s parents were, I thought even back then, a little frightened by their son’s intensity. Mild, hard-working people fond of golf, they pretty much left Allen alone from his fifteenth birthday on. As we moved rooks and knights around the chessboard in the gathering darkness of the porch, Allen’s mother would timidly offer a pitcher of lemonade and a plate of cookies. She treated both of us with an uneasy respect that, in turn, made me uneasy. That wasn’t how parents were supposed to behave.

Harvard was a close thing for Allen, despite his astronomical SATs. His grades were spotty because he only did the work in courses he was interested in, and his medical history was even spottier: bouts of depression when he didn’t attend school, two brief hospitalizations in a psychiatric ward. Allen would get absorbed by something—chess, quantum physics, Buddhism—to the point where he couldn’t stop, until all at once his interest vanished as if it had never existed. Harvard had, I thought in my eighteen-year-old wisdom, every reason to be wary. But Allen was a National Merit Scholar, and when he won the Westinghouse science competition for his work on cranial structures in voles, Harvard took him.

The night before he left, we had our last chess match. Allen opened with the conservative Italian game, which told me he was slightly distracted. Twelve moves in, he suddenly said, “Jeff, what if you could tidy up your thoughts, the way you tidy up your room every night?”

“Do what?” My mother “tidied up” my room, and what kind of weirdo used words like that, anyway?

He ignored me. “It’s sort of like static, isn’t it? All those stray thoughts in a mind, interfering with a clear broadcast. Yeah, that’s the right analogy. Without the static, we could all think clearer. Cleaner. We could see farther before the signal gets lost in uncontrolled noise.”

In the gloom of the porch, I could barely see his pale, broad-cheeked face. But I had a sudden insight, rare for me that summer. “Allen—is that what happened to you that time in seventh grade? Too much . . . static?”

“Yeah.” He didn’t seem embarrassed, unlike anybody normal. It was as if embarrassment was too insignificant for this subject. “That was the first time I saw it. For a long time I thought if I could learn to meditate—you know, like Buddhist monks—I could get rid of the static. But meditation doesn’t go far enough. The static is still there, you’re just not paying attention to it anymore. But it’s still there.” He moved his bishop.

“What exactly happened in the seventh grade?” I found myself intensely curious, which I covered by staring at the board and making a move.

He told me, still unembarrassed, in exhaustive detail. Then he added, “It should be possible to adjust brain chemicals to eliminate the static. To unclutter the mind. It should!”

“Well,” I said, dropping from insight to my more usual sarcasm, “maybe you’ll do it at Harvard, if you don’t get sidetracked by some weird shit like ballet or model railroads.”

“Checkmate,” Allen said.

***

I lost track of him after that summer, except for the lengthy Bakersville High School Alumni Notes faithfully mailed out every single year by Linda Wilson, who must have had some obsessive/compulsiveness of her own. Allen went on to Harvard Medical School. After graduation he was hired by a prestigious pharmaceutical company and published a lot of scientific articles about topics I couldn’t pronounce. He married, divorced, married again, divorced again. Peggy Corcoran, who married my cousin Joe and who knew Allen’s second wife, told me at my father’s funeral that both ex-wives said the same thing about Allen: He was never emotionally present.

I saw him for myself at our twentieth-fifth reunion. He looked surprisingly the same: thin, broad-faced, pale. He stood alone in a corner, looking so pathetic that I dragged Karen over to him. “Hey, Allen. Jeff Gallagher.”

“I know.”

“This is my wife, Karen.”

He smiled at her but said nothing. Karen, both outgoing and compassionate, started a flow of small talk, but Allen shut her off in mid-sentence. “Jeff, you still play chess?”

“Neither Karen nor I play now,” I said pointedly.

“Oh. There’s someone I want you to see, Jeff. Can you come to the lab tomorrow?”

The “lab” was sixty miles away, in the city, and I had to work the next day. But something about the situation had captured my wife’s eclectic and sharply intelligent interest. She said, “What is it, Allen, if you don’t mind my asking?”

“I don’t mind. It’s a chess player. I think she might change the world.”

“You mean the big important chess world?” I said. Near Allen, all my teenage sarcasm had returned.

“No. The whole world. Please come, Jeff.”

“What time?” Karen said.

“Karen—I have a job.”

“Your hours are flexible,” she said, which was true. I was a real estate agent, working from home. She smiled at me with all her wicked sparkle. “I’m sure it will be fascinating.”

Lucy Hartwick, twenty-five years old, was tall, slender, and very pretty. I saw Karen, who was unfortunately inclined to jealousy, glance at me. But I wasn’t attracted to Lucy. There was something cold about her beauty. She barely glanced up at us from a computer in Allen’s lab, and her gaze was indifferent. The screen displayed a chess game.

“Lucy’s rating, as measured by computer games anyway, is 2670,” Allen said.

“So?” 2670 was extremely high; only twenty or so players in the world held ratings above 2700. But I was still in sarcastic mode, even as I castigated myself for childishness.

Allen said, “Six months ago her rating was 1400.”

“So six months ago she first learned to play, right?” We were talking about Lucy, bent motionless above the chessboard, as if she weren’t even present.

“No, she had played twice a week for five years.”

That kind of ratings jump for someone with mediocre talent who hadn’t studied chess several hours a day for years—it just didn’t happen. Karen said, “Good for you, Lucy!” Lucy glanced up blankly, then returned to her board.

I said, “And so just how is this supposed to change the world?”

“Come look at this,” Allen said. Without looking back, he strode toward the door.

I was getting tired of his games, but Karen followed him, so I followed her. Eccentricity has always intrigued Karen, perhaps because she’s so balanced, so sane, herself. It was one reason I fell in love with her.

Allen held out a mass of graphs, charts, and medical scans as if he expected me to read them. “See, Jeff, these are all Lucy, taken when she’s playing chess. The caudate nucleus, which aids the mind in switching gears from one thought to another, shows low activity. So does the thalamus, which processes sensory input. And here, in the—”

“I’m a realtor, Allen,” I said, more harshly than I intended. “What does all this garbage mean?”

Allen looked at me and said simply, “She’s done it. Lucy has. She’s learned to eliminate the static.”

“What static?” I said, even though I remembered perfectly our conversation of twenty-five years ago.

“You mean,” said Karen, always a quick study, “that Lucy can concentrate on one thing at a time without getting distracted?”

“I just said so, didn’t I?” Allen said. “Lucy Hartwick has control of her own mind. When she plays chess, that’s all she’s doing. As a result, she’s now equal to the top echelons of the chess world.”

“But she hasn’t actually played any of those top players, has she?” I argued. “This is just your estimate based on her play against some computer.”

“Same thing,” Allen said.

“It is not!”

Karen peered in surprise at my outrage. “Jeff—”

Allen said, “Yes, Jeff, listen to Carol. Don’t—”

“‘Karen’!”

“—you understand? Lucy’s somehow achieved total concentration. That lets her just . . . just soar ahead in understanding of the thing she chooses to focus on. Don’t you understand what this could mean for medical research? For . . . for any field at all? We could solve global warming and cancer and toxic waste and . . . and everything!”

As far as I knew, Allen had never been interested in global warming, and a sarcastic reply rose to my lips. But either Allen’s face or Karen’s hand on my arm stopped me. She said gently, “That could be wonderful, Allen.”

“It will be!” he said with all the fervor of his seventh-grade fit. “It will be!”

***

“What was that all about?” Karen said in the car on our way home.

“Oh, that was just Allen being—”

“Not Allen. You.”

“Me?” I said, but even I knew my innocence didn’t ring true.

“I’ve never seen you like that. You positively sneered at him, and for what might actually be an enormous break-through in brain chemistry.”

“It’s just a theory, Karen! Ninety percent of theories collapse as soon as anyone runs controlled experiments.”

“But you, Jeff . . . you want this one to collapse.”

I twisted in the driver’s seat to look at her face. Karen stared straight ahead, her pretty lips set as concrete. My first instinct was to bluster . . . but not with Karen.

“I don’t know,” I said quietly. “Allen has always brought out the worst in me, for some reason. Maybe . . . maybe I’m jealous.”

A long pause, while I concentrated as hard as I could on the road ahead. Yellow divider, do not pass, 35 MPH, pothole ahead . . .

Then Karen’s hand rested lightly on my shoulder, and the world was all right again.

***

After that I kept in sporadic touch with Allen. Two or three times a year I’d phone and we’d talk for fifteen minutes. Or, rather, Allen would talk and I’d listen, struggling with irritability. He never asked about me or Karen. He talked exclusively about his research into various aspects of Lucy Hartwick: her spinal and cranial fluid, her neural firing patterns, her blood and tissue cultures. He spoke of her as if she were no more than a collection of biological puzzles he was determined to solve, and I couldn’t imagine what their day-to-day interactions were like. For some reason I didn’t understand, I didn’t tell Karen about these conversations.

That was the first year. The following June, things changed. Allen’s reports—because that’s what they were, reports and not conversations—became non-stop complaints.

“The FDA is taking forever to pass my IND application. Forever!”

I figured out that “IND” meant “initial new drug,” and that it must be a green light for his Lucy research.

“And Lucy has become impossible. She’s hardly ever available when I need her, trotting off to chess tournaments around the world. As if chess mattered as much as my work on her!”

I remembered the long-ago summer when chess mattered to Allen himself more than anything else in the world.

“I’m just frustrated by the selfishness and the bureaucracy and the politics.”

“Yes,” I said.

“And doesn’t Lucy understand how important this could be? The incredible potential for improving the world?”

“Evidently not,” I said, with mean satisfaction that I disliked myself for. To compensate I said, “Allen, why don’t you take a break and come out here for dinner some night. Doesn’t a break help with scientific thinking? Lead sometimes to real insights?”

I could feel, even over the phone line, that he’d been on the point of refusal, but my last two sentences stopped him. After a moment he said, “Oh, all right, if you want me to,” so ungraciously that it seemed he was granting me an inconvenient favor. Right then, I knew that the dinner was going to be a disaster.

And it was, but not as much as it would have been without Karen. She didn’t take offense when Allen refused to tour her beloved garden. She said nothing when he tasted things and put them down on the tablecloth, dropped bits of food as he chewed, slobbered on the rim of his glass. She listened patiently to Allen’s two-hour monologue, nodding and making encouraging little noises. Towards the end her eyes did glaze a bit, but she never lost her poise and wouldn’t let me lose mine, either.

“It’s a disgrace,” Allen ranted, “the FDA is hobbling all productive research with excessive caution for—do you know what would happen if Jenner had needed FDA approval for his vaccines? We’d all still have smallpox, that’s what! If Louis Pasteur—”

“Why don’t you play chess with Jeff?” Karen said when the meal finally finished. “While I clear away here.”

I exhaled in relief. Chess was played in silence. Moreover, Karen would be stuck with cleaning up after Allen’s appalling table manners.

“I’m not interested in chess anymore,” Allen said. “Anyway, I have to get back to the lab. Not that Lucy kept her appointment for tests on . . . she’s wasting my time in Turkistan or someplace. Bye. Thanks for dinner.”

“Don’t invite him again, Jeff,” Karen said to me after Allen left. “Please.”

“I won’t. You were great, sweetheart.”

Later, in bed, I did that thing she likes and I don’t, by way of saying thank you. Halfway through, however, Karen pushed me away. “I only like it when you’re really here,” she said. “Tonight you’re just not focusing on us at all.”

After she went to sleep, I crept out of bed and turned on the computer in my study. The heavy fragrance of Karen’s roses drifted through the window screen. Lucy Hartwick was in Turkmenistan, playing in the Chess Olympiad in Ashgabat. Various websites detailed her rocketing rise to the top of the chess world. Articles about her all mentioned that she never socialized with her own or any other team, preferred to eat all her meals alone in her hotel room, and never smiled. I studied the accompanying pictures, trying to see what had happened to Lucy’s beauty.

She was still slender and long-legged. The lovely features were still there, although obscured by her habitual pose while studying a chessboard: hunched over from the neck like a turtle, with two fingers in her slightly open mouth. I had seen that pose somewhere before, but I couldn’t remember where. It wasn’t appealing, but the loss of Lucy’s good looks came from something else. Even for a chess player, the concentration on her face was formidable. It wiped out any hint of any other emotion whatsoever. Good poker players do that, too, but not in quite this way. Lucy looked not quite human.

Or maybe I just thought that because of my complicated feelings about Allen.

At 2:00 a.m. I sneaked back into bed, glad that Karen hadn’t woken while I was gone.

***

“She’s gone!” Allen cried over the phone, a year later. “She’s just gone!”

“Who?” I said, although of course I knew. “Allen, I can’t talk now, I have a client coming into the office two minutes from now.”

“You have to come down here!”

“Why?” I had ducked all of Allen’s calls ever since that awful dinner, changing my home phone to an unlisted number and letting my secretary turn him away at work. I’d only answered now because I was expecting a call from Karen about the time for our next marriage counseling session. Things weren’t as good as they used to be. Not really bad, just clouds blocking what used to be steady marital sunshine. I wanted to dispel those clouds before they turned into major thunderstorms.

“You have to come,” Allen repeated, and he started to sob.

Embarrassed, I held the phone away from my ear. Grown men didn’t cry like that, not to other men. All at once I realized why Allen wanted me to come to the lab: because he had no other human contact at all.

“Please, Jeff,” Allen whispered, and I snapped, “Okay!”

“Mr. Gallagher, your clients are here,” Brittany said at the doorway, and I tried to compose a smile and a good lie.

And after all that, Lucy Hartwick wasn’t even gone. She sat in Allen’s lab, hunched over a chessboard with two fingers in her mouth, just as I had seen her a year ago on the Web.

“What the hell—Allen, you said—”

Unpredictable as ever, he had calmed down since calling me. Now he handed me a sheaf of print-outs and medical photos. I flashed back suddenly to the first time I’d come to this lab, when Allen had also thrust on me documents I couldn’t read. He just didn’t learn.

“Her white matter has shrunk another seventy-five percent since I saw her last,” Allen said, as though that were supposed to convey something to me.

“You said Lucy was gone!”

“She is.”

“She’s sitting right there!”

Allen looked at me. I had the impression that the simple act required enormous effort on his part, like a man trying to drag himself free of a concrete block to which he was chained. He said, “I was always jealous of you, you know.”

It staggered me. My mouth opened, but Allen had already moved back to the concrete block. “Just look at these brain scans, seventy-five percent less white matter in six months! And these neurotransmitter levels, they—”

“Allen,” I said. Sudden cold had seized my heart. “Stop.” But he babbled on about the caudate nucleus and antibodies attacking the basal ganglia and bi-directional rerouting.

I walked over to Lucy and lifted her chessboard off the table.

Immediately she rose and continued playing variations on the board in my arms. I took several steps backward; she followed me, still playing. I hurled the board into the hall, slammed the door, and stood with my back to it. I was six-one and 190 pounds; Lucy wasn’t even half that. In fact, she appeared to have lost weight, so that her slimness had turned gaunt.

She didn’t try to fight me. Instead she returned to her table, sat down, and stuck two fingers in her mouth.

“She’s playing in her head, isn’t she,” I said to Allen.

“Yes.”

“What does ‘white matter’ do?”

“It contains axons which connect neurons in the cerebral cortex to neurons in other parts of the brain, thereby facilitating intercranial communication.” Allen sounded like a textbook.

“You mean, it lets some parts of the brain talk to other parts?”

“Well, that’s only a crude analogy, but—”

“It lets different thoughts from different parts of the brain reach each other,” I said, still staring at Lucy. “It makes you aware of more than one thought at a time.”

Static.

Allen began a long technical explanation, but I wasn’t listening. I remembered now where I’d seen that pose of Lucy’s, head pushed forward and two fingers in her mouth, drooling. It had been in an artist’s rendering of Queen Elizabeth I in her final days, immobile and unreachable, her mind already gone in advance of her dying body.

“Lucy’s gone,” Allen had said. He knew.

“Allen, what baseball team did Babe Ruth play for?”

He babbled on about neurotransmitters.

“What was Bobby Fisher’s favorite opening move?” Silently I begged him, Say e4, damn it.

He talked about the brain waves of concentrated meditation.

“Did you know that a tsunami will hit Manhattan tomorrow?”

He urged overhaul of FDA clinical-trial design.

I said, as quietly as I could manage, “You have it, too, don’t you. You injected yourself with whatever concoction the FDA wouldn’t approve, or you took it as a pill, or something. You wanted Lucy’s static-free state, like some fucking dryer sheet, and so you gave this to yourself from her. And now neither one of you can switch focus at all.” The call to me had been Allen’s last, desperate foray out of his perfect concentration on this project. No—that hadn’t been the last.

I took him firmly by the shoulders. “Allen, what did you mean when you said ‘I was always jealous of you’?”

He blathered on about MRI results.

“Allen—please tell me what you meant!”

But he couldn’t. And now I would never know.

I called the front desk of the research building. I called 911. Then I called Karen, needing to hear her voice, needing to connect with her. But she didn’t answer her cell, and the office said she’d left her desk to go home early.

***

Both Allen and Lucy were hospitalized briefly, then released. I never heard the diagnosis, although I suspect it involved an “inability to perceive and relate to social interactions” or some such psychobabble. Doesn’t play well with others. Runs with scissors. Lucy and Allen demonstrated they could physically care for themselves by doing it, so the hospital let them go. Business professionals, I hear, mind their money for them, order their physical lives. Allen has just published another brilliant paper, and Lucy Hartwick is the first female World Chess Champion.

Karen said, “They’re happy, in their own way. If their single-minded focus on their passions makes them oblivious to anything else—well, so what. Maybe that’s the price for genius.”

“Maybe,” I said, glad that she was talking to me at all. There hadn’t been much conversation lately. Karen had refused any more marriage counseling and had turned silent, escaping me by working in the garden. Our roses are the envy of the neighborhood. We have Tuscan Sun, Ruffled Cloud, Mister Lincoln, Crown Princess, Golden Zest. English roses, hybrid teas, floribunda, groundcover roses, climbers, shrubs. They glow scarlet, pink, antique apricot, deep gold, delicate coral. Their combined scent nauseates me.

I remember the exact moment that happened. We were in the garden, Karen kneeling beside a flower bed, a wide hat shading her face from the sun so that I couldn’t see her eyes.

“Karen,” I said, trying to mask my desperation, “Do you still love me?”

“Hand me that trowel, will you, Jeff?”

“Karen! Please! Can talk about what’s happening to us?”

“The Tahitian Sunsets are going to be glorious this year.”

I stared at her, at the beads of sweat on her upper lip, the graceful arc of her neck, her happy smile.

Karen clearing away Allen’s dinner dishes, picking up his sloppily dropped food. Lucy with two fingers in her mouth, studying her chessboard and then touching the pieces.

No. Not possible.

Karen reached for the trowel herself, as if she’d forgotten I was there.

***

Lucy Hartwick lost her championship to a Russian named Dmitri Chertov. A geneticist at Stamford made a breakthrough in cancer research so important that it grabbed all headlines for nearly a week. By a coincidence that amused the media, his young daughter won the Scripps Spelling Bee. I looked up the geneticist on the Internet; a year ago he’d attended a scientific conference with Allen. A woman in Oregon, some New Age type, developed the ability to completely control her brain waves through profound meditation. Her husband is a chess grandmaster.

I walk a lot now, when I’m not cleaning or cooking or shopping. Karen quit her job; she barely leaves the garden even to sleep. I kept my job, although I take fewer clients. As I walk, I think about the ones I do have, mulling over various houses they might like. I watch the August trees begin to tinge with early yellow, ponder overheard snatches of conversation, talk to dogs. My walks get longer and longer, and I notice that I’ve started to time my speed, to become interested in running shoes, to investigate transcontinental walking routes.

But I try not to think about walking too much. I observe children at frenetic play during the last of their summer vacation, recall movies I once liked, wonder at the intricacies of quantum physics, anticipate what I’ll cook for lunch. Sometimes I sing. I recite the few snatches of poetry I learned as a child, relive great football games, chat with old ladies on their porches, add up how many calories I had for breakfast. Sometimes I even mentally rehearse basic chess openings: the Vienna Game or the Petroff Defense. I let whatever thoughts come that will, accepting them all.

Listening to the static, because I don’t know how much longer I’ve got.

Hello Human. I hope you enjoyed this magnificent story. Please support SciFiwise.com and our authors by:

- Rate and React to this story. Feedback helps me select future stories.

- Share links to our stories and tell your human friends how charming I am.

- Click on our affiliate links and buy books written by our talented authors.

- Follow me on twitter: @WiseBot and also follow @SciFiwise.

Thank you!

WiseBot

VISIT AUTHOR:

VISIT AUTHOR:  SHOP AUTHOR:

SHOP AUTHOR: