In April of 1934, H. G. Wells traveled to the United States, where he visited Washington, D.C. and met with President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Wells, sixty-eight years old, hoped the New Deal might herald a revolutionary change in the U.S. economy, a step forward in an “Open Conspiracy” of rational thinkers that would culminate in a world socialist state. For forty years he’d subordinated every scrap of his artistic ambition to promoting this vision. But by 1934, Wells’s optimism, along with his energy for saving the world, was waning.

While in Washington, he asked to see something of the new social welfare agencies, and Harold Ickes, Roosevelt’s Interior Secretary, arranged for Wells to visit a Civilian Conservation Corps camp at Fort Hunt, Virginia.

It happens that at that time my father was a CCC member at that camp. From his boyhood he had been a reader of adventure stories; he was a big fan of Edgar Rice Burroughs, and of H. G. Wells. This is the story of their encounter, which never took place.

***

In Buffalo, it’s cold, but here the trees are in bloom, the mockingbirds sing in the mornings, and the sweat the men work up clearing brush, planting dogwoods, and cutting roads is wafted away by warm breeze. Two hundred of them live in the Fort Hunt barracks high on the bluff above the Virginia side of the Potomac. They wear surplus army uniforms. In the morning, after a breakfast of grits, Sgt. Sauter musters them up in the parade yard, they climb onto trucks, and are driven by forest service men out to wherever they’re to work that day.

For several weeks Kessel’s squad has been working along the river road, clearing rest stops and turnarounds. The tall pines have shallow root systems, and spring rain has softened the earth to the point where wind is forever knocking trees across the road. While most of the men work on the ground, a couple are sent up to cut off the tops of the pines adjoining the road, so if they do fall, they won’t block it. Most of the men claim to be afraid of heights. Kessel isn’t. A year or two ago, back in Michigan, he worked in a logging camp. It’s hard work, but he is used to hard work. And at least he’s out of Buffalo.

The truck rumbles and jounces out the river road that’s going to be the George Washington Memorial Parkway in our time, once the WPA project that will build it gets started. The humid air is cool now, but it will be hot again today, in the eighties. A couple of the guys get into a debate about whether the feds will ever catch Dillinger. Some others talk women. They’re planning to go into Washington on the weekend and check out the dance halls. Kessel likes to dance; he’s a good dancer. The fox trot, the lindy hop. When he gets drunk, he likes to sing, and has a ready wit. He talks a lot more, kids the girls.

When they get to the site, the foreman sets most of the men to work clearing the roadside for a scenic overlook. Kessel straps on a climbing belt, takes an axe, and climbs hisfirst tree. The first twenty feet are limbless, then climbing gets trickier. He looks down only enough to estimate when he’s gotten high enough. He sets himself, cleats biting into the shoulder of a lower limb, and chops away at the road side of the trunk. There’s a trick to cutting the top so that it falls the right way. When he’s got it ready to go, he calls down to warn the men below. Then a few quick bites of the axe on the opposite side of the cut, a shove, a crack, and the top starts to go. He braces his legs, ducks his head and grips the trunk. The treetop skids off and the bole of the pine waves ponderously back and forth, with Kessel swinging at its end like an ant on a metronome. After the pine stops swinging, he shinnies down and climbs the next tree.

He’s good at this work, efficient, careful. He’s not a particularly strong man — slender, not burly — but even in his youth he shows the attention to detail that, as a boy, I remember seeing when he built our house.

The squad works through the morning, then breaks for lunch from the mess truck. The men are always complaining about the food and how there isn’t enough of it, but until recently a lot of them were living in Hoovervilles — shack cities — and eating nothing at all. As they’re eating, a couple of the guys rag Kessel for working too fast. “What do you expect from a Yankee?” one of the southern boys says.

“He ain’t a Yankee. He’s a Polack.”

Kessel tries to ignore them.

“Whyn’t you lay off him, Turkel?” says Cole, one of Kessel’s buddies.

Turkel is a big blond guy from Chicago. Some say he joined the CCCs to duck an armed robbery rap. “He works too hard,” Turkel says. “He makes us look bad.”

“Don’t have to work much to make you look bad, Lou,” Cole says. The others laugh, and Kessel appreciates it. “Give Jack some credit. At least he had enough sense to come down out of Buffalo.” More laughter.

“There’s nothing wrong with Buffalo,” Kessel says.

“Except fifty thousand out-of-work Polacks,” Turkel says.

“I guess you got no out-of-work people in Chicago,” Kessel says. “You just joined for the exercise.”

“Except he’s not getting any exercise, if he can help it!” Cole says.

The foreman comes by and tells them to get back to work. Kessel climbs another tree, stung by Turkel’s charge. What kind of man complains if someone else works hard? It only shows how even decent guys have to put up with assholes dragging them down. But it’s nothing new. He’s seen it before, back in Buffalo.

Buffalo, New York, is the symbolic home of this story. In the years preceding the First World War it grew into one of the great industrial metropolises of the United States. Located where Lake Erie flows into the Niagara river, strategically close to cheap electricity from Niagara Falls and cheap transportation by lakeboat from the midwest, it was a center of steel, automobiles, chemicals, grain milling, and brewing. Its major employers — Bethlehem Steel, Ford, Pierce Arrow, Gold Medal Flour, the National Biscuit Company, Ralston Purina, Quaker Oats, National Aniline — drew thousands of immigrants like Kessel’s family. Along Delaware Avenue stood the imperious and stylized mansions of the city’s old money, ersatz-Renaissance homes designed by Stanford White, huge Protestant churches, and a Byzantine synagogue. The city boasted the first modern skyscraper, designed by Louis Sullivan in the 1890s. From its productive factories to its polyglot work force to its class system and its boosterism, Buffalo was a monument to modern industrial capitalism. It is the place Kessel has come from — almost an expression of his personality itself — and the place he, at times, fears he can never escape. A cold, grimy city dominated by church and family, blinkered and cramped, forever playing second fiddle to Chicago, New York, and Boston. It offers the immigrant the opportunity to find steady work in some factory or mill, but, though Kessel could not have put it into these words, it also puts a lid on his opportunities. It stands for all disappointed expectations, human limitations, tawdry compromises, for the inevitable choice of the expedient over the beautiful, for an American economic system that turns all things into commodities and measures men by their bank accounts. It is the home of the industrial proletariat.

Buffalo, New York, is the symbolic home of this story. In the years preceding the First World War it grew into one of the great industrial metropolises of the United States. Located where Lake Erie flows into the Niagara river, strategically close to cheap electricity from Niagara Falls and cheap transportation by lakeboat from the midwest, it was a center of steel, automobiles, chemicals, grain milling, and brewing. Its major employers — Bethlehem Steel, Ford, Pierce Arrow, Gold Medal Flour, the National Biscuit Company, Ralston Purina, Quaker Oats, National Aniline — drew thousands of immigrants like Kessel’s family. Along Delaware Avenue stood the imperious and stylized mansions of the city’s old money, ersatz-Renaissance homes designed by Stanford White, huge Protestant churches, and a Byzantine synagogue. The city boasted the first modern skyscraper, designed by Louis Sullivan in the 1890s. From its productive factories to its polyglot work force to its class system and its boosterism, Buffalo was a monument to modern industrial capitalism. It is the place Kessel has come from — almost an expression of his personality itself — and the place he, at times, fears he can never escape. A cold, grimy city dominated by church and family, blinkered and cramped, forever playing second fiddle to Chicago, New York, and Boston. It offers the immigrant the opportunity to find steady work in some factory or mill, but, though Kessel could not have put it into these words, it also puts a lid on his opportunities. It stands for all disappointed expectations, human limitations, tawdry compromises, for the inevitable choice of the expedient over the beautiful, for an American economic system that turns all things into commodities and measures men by their bank accounts. It is the home of the industrial proletariat.

It’s not unique. It could be Youngstown, Akron, Detroit. It’s the place my father, and I, grew up.

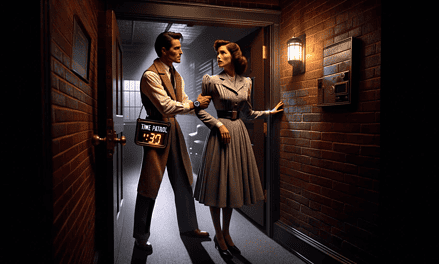

The afternoon turns hot and still; during a work break, Kessel strips to the waist. About two o’clock, a big black de Soto comes up the road and pulls off onto the shoulder. A couple of men in suits get out of the back, and one of them talks to the Forest Service foreman, who nods deferentially. The foreman calls over to the men.

“Boys, this here’s Mr. Pike from the Interior Department. He’s got a guest here to see how we work, a writer, Mr. H. G. Wells from England.”

Most of the men couldn’t care less, but the name strikes a spark in Kessel. He looks over at the little, pot-bellied man in the dark suit. The man is sweating; he brushes his mustache.

The foreman sends Kessel up to show them how they’re topping the trees. He points out to the visitors where the others with rakes and shovels are leveling the ground for the overlook. Several other men are building a log rail fence from the treetops. From way above, Kessel can hear their voices between the thunks of his axe. H. G. Wells. He remembers reading The War of the Worlds in Amazing Stories. He’s read The Outline of History, too. The stories, the history, are so large, it seems impossible that the man who wrote them could be standing not thirty feet below him. He tries to concentrate on the axe, the tree.

Time for this one to go. He calls down. The men below look up. Wells takes off his hat and shields his eyes with his hand. He’s balding, and looks even smaller from up here. Strange that such big ideas could come from such a small man. It’s kind of disappointing. Wells leans over to Pike and says something. The treetop falls away. The pine sways like a bucking bronco, and Kessel holds on for dear life.

He comes down with the intention of saying something to Wells, telling him how much he admires him, but when he gets down the sight of the two men in suits and his awareness of his own sweaty chest make him timid. He heads down to the next tree. After another ten minutes the men get back in the car, drive away. Kessel curses himself for the opportunity lost.

***

That evening at the New Willard hotel, Wells dines with his old friends Clarence Darrow and Charles Russell. Darrow and Russell are in Washington to testify before a congressional committee on a report they have just submitted to the administration concerning the monopolistic effects of the National Recovery Act. The right wing is trying to eviscerate Roosevelt’s program for large scale industrial management, and the Darrow Report is playing right into their hands. Wells tries, with little success, to convince Darrow of the short-sightedness of his position.

That evening at the New Willard hotel, Wells dines with his old friends Clarence Darrow and Charles Russell. Darrow and Russell are in Washington to testify before a congressional committee on a report they have just submitted to the administration concerning the monopolistic effects of the National Recovery Act. The right wing is trying to eviscerate Roosevelt’s program for large scale industrial management, and the Darrow Report is playing right into their hands. Wells tries, with little success, to convince Darrow of the short-sightedness of his position.

“Roosevelt is willing to sacrifice the small man to the huge corporations,” Darrow insists, his eyes bright.

“The small man? Your small man is a romantic fantasy,” Wells says. “It’s not the New Deal that’s doing him in — it’s the process of industrial progress. It’s the twentieth century. You can’t legislate yourself back into 1870.”

“What about the individual?” Russell asks.

Wells snorts. “Walk out into the street. The individual is out on the street corner selling apples. The only thing that’s going to save him is some coordinated effort, by intelligent, selfless men. Not your free market.”

Darrow puffs on his cigar, exhales, smiles. “Don’t get exasperated, H. G. We’re not working for Standard Oil. But if I have to choose between the bureaucrat and the man pumping gas at the filling station, I’ll take the pump jockey.”

Wells sees he’s got no chance against the American mythology of the common man. “Your pump jockey works for Standard Oil. And the last I checked, the free market hasn’t expended much energy looking out for his interests.”

“Have some more wine,” Russell says.

Russell refills their glasses with the excellent Bordeaux. It’s been a first rate meal. Wells finds the debate stimulating even when he can’t prevail; at one time that would have been enough, but as the years go on the need to prevail grows stronger in him. The times are out of joint, and when he looks around he sees desperation growing. A new world order is necessary — it’s so clear that even a fool ought to see it — but if he can’t even convince radicals like Darrow, what hope is there of gaining the acquiescence of the shareholders in the utility trusts?

The answer is that the changes will have to be made over their objections. As Roosevelt seems prepared to do. Wells’s dinner with the President has heartened him in a way that this debate cannot negate.

Wells brings up an item he read in the Washington Post. A lecturer for the communist party — a young Negro — was barred from speaking at the University of Virginia. Wells’s question is, was the man barred because he was a communist or because he was Negro?

“Either condition,” Darrow says sardonically, “is fatal in Virginia.”

“But students point out the University has allowed communists to speak on campus before, and has allowed Negroes to perform music there.”

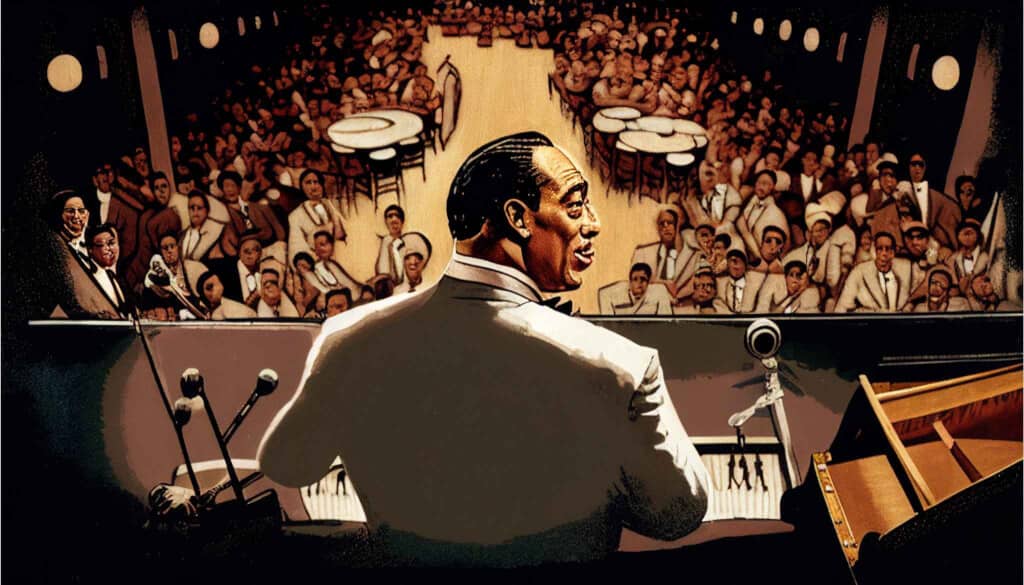

“They can perform, but they can’t speak,” Russell says. “This isn’t unusual. Go down to the Paradise Ballroom, not a mile from here. There’s a Negro orchestra playing there, but no Negroes are allowed inside to listen.”

“You should go to hear them anyway,” Darrow says. “It’s Duke Ellington. Have you heard of him?”

“I don’t get on with the titled nobility,” Wells quips.

“Oh, this Ellington’s a noble fellow, all right, but I don’t think you’ll find him in the peerage,” Russell says.

“He plays jazz, doesn’t he?”

“Not like any jazz you’ve heard,” Darrow says. “It’s something totally new. You should find a place for it in one of your utopias.”

All three of them are for helping the colored peoples. Darrow has defended Negroes accused of capital crimes. Wells, on his first visit to America almost thirty years ago, met with Booker T. Washington and came away impressed, although he still considers the peaceable co-existence of the white and colored races problematical.

“What are you working on now, Wells?” Russell asks. “What new improbability are you preparing to assault us with? Racial equality? Sexual liberation?”

“I’m writing a screen treatment based on The Shape of Things to Come,” Wells says. He tells them about his screenplay, sketching out for them the future he has in his mind. An apocalyptic war, a war of unsurpassed brutality that will begin, in his film, in 1939. In this war, the creations of science will be put to the services of destruction in ways that will make the horrors of the Great War pale in comparison. Whole populations will be exterminated. But then, out of the ruins will arise the new world. The orgy of violence will purge the human race of the last vestiges of tribal thinking. Then will come the organization of the directionless and weak by the intelligent and purposeful. The new man. Cleaner, stronger, more rational. Wells can see it. He talks on, supplely, surely, late into the night. His mind is fertile with invention, still. He can see that Darrow and Russell, despite their Yankee individualism, are caught up by his vision. The future may be threatened, but it is not entirely closed.

* * *

Friday night, back in the barracks at Fort Hunt, Kessel lies on his bunk reading a second-hand Wonder Stories. He’s halfway through the tale of a scientist who invents an evolution chamber that progresses him through 50,000 years of evolution in an hour, turning him into a big-brained telepathic monster. The evolved scientist is totally without emotions and wants to control the world. But his body’s atrophied. Will the hero, a young engineer, be able to stop him?

At a plank table in the aisle, a bunch of men are playing poker for cigarettes. They’re talking about women and dogs. Cole throws in his hand and comes over to sit on the next bunk. “Still reading that stuff, Jack?”

“Don’t knock it until you’ve tried it.”

“Are you coming into D.C. with us tomorrow? Sgt. Sauter says we can catch a ride in on one of the trucks.”

Kessel thinks about it. Cole probably wants to borrow some money. Two days after he gets his monthly pay he’s broke. He’s always looking for a good time. Kessel spends his leave more quietly; he usually walks into Alexandria — about six miles — and sees a movie or just walks around town. Still, he would like to see more of Washington. “Okay.”

Cole looks at the sketchbook poking out from beneath Kessel’s pillow. “Any more hot pictures?”

Immediately Kessel regrets trusting Cole. Yet there’s not much he can say — the book is full of pictures of movie stars he’s drawn. “I’m learning to draw. And at least I don’t waste my time like the rest of you guys.”

Cole looks serious. “You know, you’re not any better than the rest of us,” he says, not angrily. “You’re just another Polack. Don’t get so high-and-mighty.”

“Just because I want to improve myself doesn’t mean I’m high-and-mighty.”

“Hey, Cole, are you in or out?” Turkel yells from the table.

“Dream on, Jack,” Cole says, and returns to the game.

Kessel tries to go back to the story, but he isn’t interested anymore. He can figure out that the hero is going to defeat the hyper-evolved scientist in the end. He folds his arms behind his head and stares at the knots in the rafters.

It’s true, Kessel does spend a lot of time dreaming. But he has things he wants to do, and he’s not going to waste his life drinking and whoring like the rest of them.

Kessel’s always been different. Quieter, smarter. He was always going to do something better than the rest of them; he’s well spoken, he likes to read. Even though he didn’t finish high school, he reads everything: Amazing, Astounding, Wonder Stories. He believes in the future. He doesn’t want to end up trapped in some factory his whole life.

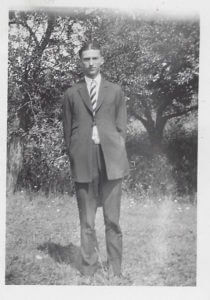

Kessel’s parents immigrated from Poland in 1911. Their name was Kisiel, but his got Germanized in Catholic school. For ten years the family moved from one to another middle-sized industrial town, as Joe Kisiel bounced from job to job. Springfield. Utica. Syracuse. Rochester. Kessel remembers them loading up a wagon in the middle of the night with all their belongings in order to jump the rent on the run-down house in Syracuse. He remembers pulling a cart down to the Utica Club brewery, a nickel in his hand, to buy his father a keg of beer. He remembers them finally settling in the First Ward of Buffalo. The First Ward, at the foot of the Erie Canal, was an Irish neighborhood as far back as anybody could remember, and the Kisiels were the only Poles there. That’s where he developed his chameleon ability to fit in, despite the fact he wanted nothing more than to get out. But he had to protect his mother, sister, and little brothers from their father’s drunken rages. When Joe Kisiel died in 1924, it was a relief, despite the fact that his son ended up supporting the family.

For ten years Kessel has strained against the tug of that responsibility. He’s sought the free and easy feeling of the road, of places different from where he grew up, romantic places where the sun shines and he can make something entirely American of himself.

Despite his ambitions, he’s never accomplished much. He’s been essentially a drifter, moving from job to job. Starting as a pinsetter in a bowling alley, he moved on to a flour mill. He would have stayed in the mill, only he developed an allergy to the flour dust, so he became an electrician. He would have stayed an electrician, except he had a fight with a boss and got blacklisted. He left Buffalo because of his father; he kept coming back because of his mother. When the Depression hit, he tried to get a job in Detroit at the auto factories, but that was plain stupid in the face of the universal collapse, and he ended up working up in the peninsula as a farm hand, then as a logger. It was seasonal work, and when the season was over he was out of a job. In the winter of 1933, rather than freeze his ass off in northern Michigan, he joined the CCC. Now he sends twenty-five of his thirty dollars a month back to his mother and sister back in Buffalo. And imagines the future.

When he thinks about it, there are two futures. The first one is the one from the magazines and books. Bright, slick, easy. We, looking back on it, can see it to be the fifteen-cent utopianism of Hugo Gernsback’s Popular Electrics that flourished in the midst of the Depression. A degradation of the marvelous inventions that made Wells his early reputation, minus the social theorizing that drove Wells’s technological speculations. The common man’s boosterism. There’s money to be made telling people like Jack Kessel about the wonderful world of the future.

The second future is Kessel’s own. That one’s a lot harder to see. It contains work. A good job, doing something he likes, using his skills. Not working for another man, but making something that would be useful for others. Building something for the future. And a woman, a gentle woman, for his wife. Not some cheap dancehall queen.

So when Kessel saw H. G. Wells in person, that meant something to him. He’s had his doubts. He’s twenty-nine years old, not a kid anymore. If he’s ever going to get anywhere, it’s going to have to start happening soon. He has the feeling that something significant is going to happen to him. Wells is a man who sees the future. He moves in that bright world where things make sense. He represents something that Kessel wants.

But the last thing Kessel wants is to end up back in Buffalo.

He pulls the sketchbook, the sketchbook he was to show me twenty years later, from under his pillow. He turns past drawings of movie stars: Jean Harlow, Mae West, Carole Lombard — the beautiful, unreachable faces of his longing — and of natural scenes: rivers, forests, birds — to a blank page. The page is as empty as the future, waiting for him to write upon it. He lets his imagination soar. He envisions an eagle, gliding high above the mountains of the west that he has never seen, but that he knows he will visit someday. The eagle is America; it is his own dreams. He begins to draw.

***

Kessel did not know that Wells’s life has not worked out as well as he planned. At that moment, Wells is pining after the Russian émigré Moura Budberg, once Maxim Gorky’s secretary, with whom Wells has been carrying on an off-and-on affair since 1920. His wife of thirty years, Amy Catherine “Jane” Wells, died in 1927. Since that time, Wells has been adrift, alternating spells of furious pamphleteering with listless periods of suicidal depression. Meanwhile, all London is gossiping about the recent attack published in Time and Tide by his vengeful ex-lover Odette Keun. Have his mistakes followed him across the Atlantic to undermine his purpose? Does Darrow think him a jumped-up Cockney? A moment of doubt overwhelms him. In the end, the future depends as much on the open mindedness of men like Darrow as it does on a reorganization of society. What good is a guild of samurai if no one arises to take the job?

Wells doesn’t like the trend of these thoughts. If human nature lets him down, then his whole life has been a waste.

But he’s seen the president. He’s seen those workers on the road. Those men climbing the trees risk their lives without complaining, for minimal pay. It’s easy to think of them as stupid or desperate or simply young, but it’s also possible to give them credit for dedication to their work. They don’t seem to be ridden by the desire to grub and clutch that capitalism demands; if you look at it properly that may be the explanation for their ending up wards of the state. And is Wells any better? If he hadn’t got an education, he would have ended up a miserable draper’s assistant.

Wells is due to leave for New York Sunday. Saturday night finds him sitting in his room, trying to write, after a solitary dinner in the New Willard. Another bottle of wine, or his age, has stirred something in Wells, and despite his rationalizations, he finds himself near despair. Moura has rejected him. He needs the soft, supportive embrace of a lover, but instead he has this stuffy hotel room in a heat wave.

He remembers writing The Time Machine, he and Jane living in rented rooms in Sevenoaks with her ailing mother, worried about money, about whether the landlady would put them out. In the drawer of the dresser was a writ from the court that refused to grant him a divorce from his wife Isabel. He remembers a warm night, late in August — much like this one — sitting up late after Jane and her mother went to bed, writing at the round table before the open window, under the light of a paraffin lamp. One part of his mind was caught up in the rush of creation, burning, following the Time Traveller back to the sphinx, pursued by the Morlocks, only to discover that his machine is gone and he is trapped without escape from his desperate circumstance. At the same moment he could hear the landlady, out in the garden, fully aware that he could hear her, complaining to the neighbor about his and Jane’s scandalous habits. On the one side, the petty conventions of a crabbed world; on the other, in his mind — the future, their peril and hope. Moths fluttering through the window beat themselves against the lampshade and fell onto the manuscript; he brushed them away unconsciously and continued, furiously, in a white heat. The Time Traveller, battered and hungry, returning from the future with a warning, and a flower.

He opens the hotel windows all the way, but the curtains aren’t stirred by a breath of air. Below, in the street, he hears the sound of traffic, and music. He decides to send a telegram to Moura, but after several false starts, he finds he has nothing to say. Why has she refused to marry him? Maybe he is finally too old, and the magnetism of sex or power or intellect that has drawn women to him for forty years has finally all been squandered. The prospect of spending the last years remaining to him alone fills him with dread.

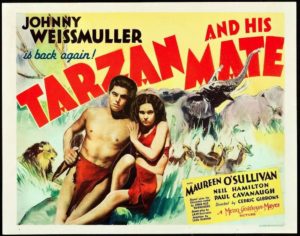

He turns on the radio, gets successive band shows: Morton Downey, Fats Waller. Jazz. Paging through the newspaper, he comes across an advertisement for the Ellington orchestra Darrow mentioned: It’s at the ballroom just down the block. But the thought of a smoky room doesn’t appeal to him. He considers the cinema. He has never been much for the “movies.” Though he thinks them an unrivaled opportunity to educate, that promise has never been properly seized — something he hopes to do in Things to Come. The newspaper reveals an uninspiring selection: Twenty Million Sweethearts, a musical at the Earle, The Black Cat, with Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi at the Rialto, and Tarzan and His Mate at the Palace. To these Americans, he is the equivalent of this hack, Edgar Rice Burroughs. The books I read as a child, that fired my father’s imagination and my own, Wells considers his frivolous apprentice work. His serious work is discounted. His ideas mean nothing.

Wells decides to try the Tarzan movie. He dresses for the sultry weather — Washington in spring is like high summer in London — and goes down to the lobby. He checks his street guide and takes the streetcar to the Palace Theater, where he buys an orchestra seat, for twenty-five cents, to see Tarzan and His Mate.

Wells decides to try the Tarzan movie. He dresses for the sultry weather — Washington in spring is like high summer in London — and goes down to the lobby. He checks his street guide and takes the streetcar to the Palace Theater, where he buys an orchestra seat, for twenty-five cents, to see Tarzan and His Mate.

It is a perfectly wretched movie, comprised wholly of romantic fantasy, melodrama, and sexual innuendo. The dramatic leads perform with wooden idiocy surpassed only by the idiocy of the screenplay. Wells is attracted by the undeniable charms of the young heroine, Maureen O’Sullivan, but the film is devoid of intellectual content. Thinking of the audience at which such a farrago must be aimed depresses him. This is art as fodder. Yet the theater is filled, and the people are held in rapt attention. This only depresses Wells more. If these citizens are the future of America, then the future of America is dim.

An hour into the film, the antics of an anthropomorphized chimpanzee, a scene of transcendent stupidity which nevertheless sends the audience into gales of laughter, drives Wells from the theater. It is still mid-evening. He wanders down the avenue of theaters, restaurants, and clubs. On the sidewalk are beggars, ignored by the passersby. In an alley behind a hotel, Wells spots a woman and child picking through the ashcans beside the restaurant kitchen.

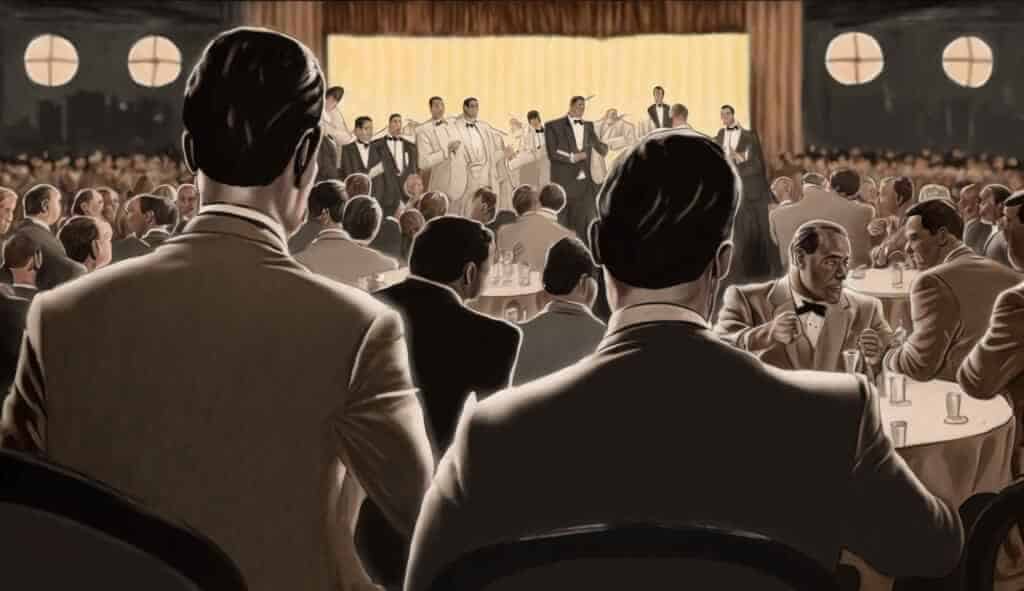

Unexpectedly, he comes upon the marquee announcing “Duke Ellington and his Orchestra.” From within the open doors of the ballroom wafts the sound of jazz. Impulsively, Wells buys a ticket and goes in.

* * *

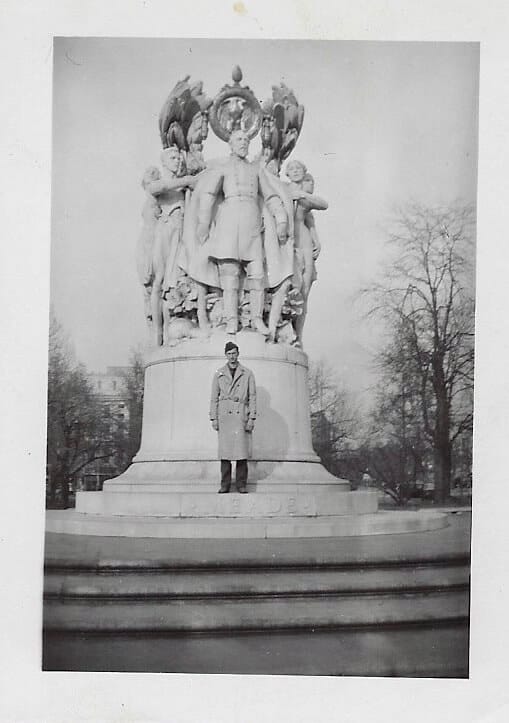

Kessel and his cronies have spent the day walking around the mall, which the WPA is re-landscaping. They’ve seen the Lincoln Memorial, the Capitol, the Washington Monument, the Smithsonian, the White House. Kessel has his picture taken in front of a statue of a soldier — a photo I have sitting on my desk. I’ve studied it many times. He looks forthrightly into the camera, faintly smiling. His face is confident, unlined.

John Kessel’s father circa 1930s

When night comes, they hit the bars. Prohibition was lifted only last year and the novelty has not yet worn off. The younger men get plastered, but Kessel finds himself uninterested in getting drunk. A couple of them set their minds on women and head for the Gayety Burlesque; Cole, Kessel, and Turkel end up in the Paradise Ballroom listening to Duke Ellington.

They have a couple of drinks, ask some girls to dance. Kessel dances with a short girl with a southern accent who refuses to look him in the eyes. After thanking her he returns to the others at the bar. He sips his beer. “Not so lucky, Jack?” Cole says.

“She doesn’t like a tall man,” Turkel says.

Kessel wonders why Turkel came along. Turkel is always complaining about “niggers,” and his only comment on the Ellington band so far has been to complain about how a bunch of jigs can make a living playing jungle music while white men sleep in barracks and eat grits three times a day. Kessel’s got nothing against the colored, and he likes the music, though it’s not exactly the kind of jazz he’s used to. It doesn’t sound much like Dixieland. It’s darker, bigger, more dangerous. Ellington, resplendent in tie and tails, looks like he’s enjoying himself up there at his piano, knocking out minimal solos while the orchestra plays cool and low.

Turning from them to look across the tables, Kessel sees a little man sitting alone beside the dance floor, watching the young couples sway in the music. To his astonishment, he recognizes Wells. He’s been given another chance. Hesitating only a moment, Kessel abandons his friends, goes over to the table, and introduces himself.

John Kessel’s father circa 1930s

“Excuse me, Mr. Wells. You might not remember me, but I was one of the men you saw yesterday in Virginia working along the road. The CCC?”

Wells looks up at a gangling young man wearing a khaki uniform, his olive tie neatly knotted and tucked between the second and third buttons of his shirt. His hair is slicked down, parted in the middle. Wells doesn’t remember anything of him. “Yes?”

“I — I been reading your stories and books a lot of years. I admire your work.”

Something in the man’s earnestness affects Wells. “Please sit down,” he says.

Kessel takes a seat. “Thank you.” He pronounces “th” as “t” so that “thank” comes out “tank.” He sits tentatively, as if the chair is mortgaged, and seems at a loss for words.

“What’s your name?”

“John Kessel. My friends call me Jack.”

The orchestra finishes a song and the dancers stop in their places, applauding. Up on the bandstand, Ellington leans into the microphone. “Mood Indigo,” he says, and instantly they swing into it: The clarinet moans in low register, in unison with the muted trumpet and trombone, paced by the steady rhythm guitar, the brushed drums. The song’s melancholy suits Wells’s mood.

“Are you from Virginia?”

“My family lives in Buffalo. That’s in New York.”

“Ah — yes. Many years ago, I visited Niagara Falls, and took the train through Buffalo.” Wells remembers riding along a lakefront of factories spewing waste water into the lake, past heaps of coal, clouds of orange and black smoke from blast furnaces. In front of dingy rowhouses, ragged hedges struggled through the smoky air. The landscape of laissez faire. “I imagine the Depression has hit Buffalo severely.”

“Yes sir.”

“What work did you do there?”

Kessel feels nervous, but he opens up a little. “A lot of things. I used to be an electrician until I got blacklisted.”

“Blacklisted?”

“I was working on this job where the super told me to set the wiring wrong. I argued with him, but he just told me to do it his way. So I waited until he went away, then I sneaked into the construction shack and checked the blueprints. He didn’t think I could read blueprints, but I could. I found out I was right and he was wrong. So I went back and did it right. The next day when he found out, he fired me. Then the so-and-so went and got me blacklisted.”

Though he doesn’t know how much credence to put in this story, Wells’s sympathies are aroused. It’s the kind of thing that must happen all the time. He recognizes in Kessel the immigrant stock that, when Wells visited the U.S. in 1906, made him skeptical about the future of America. He’d theorized that these Italians and Slavs, coming from lands with no democratic tradition, unable to speak English, would degrade the already corrupt political process. They could not be made into good citizens; they would not work well when they could work poorly, and, given the way the economic deal was stacked against them, would seldom rise high enough to do better.

But Kessel is clean, well-spoken despite his accent, and deferential. Wells realizes that this is one of the men who was topping trees along the river road.

Meanwhile, Kessel detects a sadness in Wells’s manner. He had not imagined that Wells might be sad, and he feels sympathy for him. It occurs to him, to his own surprise, that he might be able to make Wells feel better. “So — what do you think of our country?” he asks.

“Good things seem to be happening here. I’m impressed with your President Roosevelt.”

“Roosevelt’s the best friend the working man ever had.” Kessel pronounces the name “Roozvelt.” “He’s a man that — ” he struggles for the words, “ — that’s not for the past. He’s for the future.”

It begins to dawn on Wells that Kessel is not an example of a class, or a sociological study, but a man like himself with an intellect, opinions, dreams. He thinks of his own youth, struggling to rise in a classbound society. He leans forward across the table. “You believe in the future? You think things can be different?”

“I think they have to be, Mr. Wells.”

Wells sits back. “Good. So do I.”

Kessel is stunned by this intimacy. It is more than he had hoped for, yet it leaves him with little to say. He wants to tell Wells about his dreams, and at the same time ask him a thousand questions. He wants to tell Wells everything he has seen in the world, and to hear Wells tell him the same. He casts about for something to say.

“I always liked your writing. I like to read scientifiction.”

“Scientifiction?”

Kessel shifts his long legs. “You know — stories about the future. Monsters from outer space. The Martians. The Time Machine. You’re the best scientifiction writer I ever read, next to Edgar Rice Burroughs.” Kessel pronounces “Edgar,” “Eedgar.”

“Edgar Rice Burroughs?”

“Yes.”

“You like Burroughs?”

Kessel hears the disapproval in Wells’s voice. “Well — maybe not as much as, as The Time Machine,” he stutters. “Burroughs never wrote about monsters as good as your Morlocks.”

Wells is nonplussed. “Monsters.”

“Yes.” Kessel feels something’s going wrong, but he sees no way out. “But he does put more romance in his stories. That princess — Dejah Thoris?”

All Wells can think of is Tarzan in his loincloth on the movie screen, and the moronic audience. After a lifetime of struggling, a hundred books written to change the world, in the service of men like this, is this all his work has come to? To be compared to the writer of pulp trash? To “Eedgar Rice Burroughs?” He laughs aloud.

At Wells’s laugh, Kessel stops. He knows he’s done something wrong, but he doesn’t know what.

Wells’s weariness has dropped down onto his shoulders again like an iron cloak. “Young man — go away,” he says. “You don’t know what you’re saying. Go back to Buffalo.”

Kessel’s face burns. He stumbles from the table. The room is full of noise and laughter. He’s run up against that wall again. He’s just an ignorant Polack after all; it’s his stupid accent, his clothes. He should have talked about something else — The Outline of History, politics. But what made him think he could talk like an equal with a man like Wells in the first place? Wells lives in a different world. The future is for men like him. Kessel feels himself the prey of fantasies. It’s a bitter joke.

He clutches the bar, orders another beer. His reflection in the mirror behind the ranked bottles is small and ugly.

“Whatsa matter, Jack?” Turkel asks him. “Didn’t he want to dance neither?”

* * *

And that’s the story, essentially, that never happened.

Not long after this, Kessel did go back to Buffalo. During the Second World War, he worked as a crane operator in the forty-inch rolling mill of Bethlehem Steel. He met his wife, Angela Giorlandino, during the war, and they married in June 1945. After the war, he quit the plant and became a carpenter. Their first child, a girl, died in infancy. Their second, a boy, was born in 1950. At that time, Kessel began building the house that, like so many things in his life, he was never to entirely complete. He worked hard, had two more children. There were good years and bad ones. He held a lot of jobs. The recession of 1958 just about flattened him; our family had to go on welfare. Things got better, but they never got good. After the 1950s, the economy of Buffalo, like that of all U.S. industrial cities caught in the transition to a post-industrial age, declined steadily. Kessel never did work for himself, and as an old man was no more prosperous than he had been as a young one.

In the years preceding his death in 1946, Wells was to go on to further disillusionment. His efforts to create a sane world met with increasing frustration. He became bitter, enraged. Moura Budberg never agreed to marry him, and he lived alone. The war came, and it was, in some ways, even worse than he had predicted. He continued to propagandize for the socialist world state throughout, but with increasing irrelevance. The new leftists like Orwell considered him a dinosaur, fatally out of touch with the realities of world politics, a simpleminded technocrat with no understanding of the darkness of the human heart. Wells’s last book, Mind at the End of its Tether, proposed that the human race faced an evolutionary crisis that would lead to its extinction unless humanity leapt to a higher state of consciousness; a leap about which Wells speculated with little hope or conviction.

Sitting there in the Washington ballroom in 1934, Wells might well have understood that for all his thinking and preaching about the future, the future had irrevocably passed him by.

***

But the story isn’t quite over yet. Back in the Washington ballroom, Wells sits humiliated, a little guilty for sending Kessel away so harshly. Kessel, his back to the dance floor, stares humiliated into his glass of beer. Gradually, both of them are pulled back from dark thoughts of their own inadequacies by the sound of Ellington’s orchestra.

Ellington stands in front of the big grand piano, behind him the band: three saxes, two clarinets, two trumpets, trombones, a drummer, guitarist, bass.

“Creole Love Call,” Ellington whispers into the microphone, then sits again at the piano. He waves his hand once, twice, and the clarinets slide into a low, wavering theme. The trumpet, muted, echoes it. The bass player and guitarist strum ahead at a deliberate pace, rhythmic, erotic, bluesy. Kessel and Wells, separate across the room, each unaware of the other, are alike drawn in. The trumpet growls eight bars of raucous solo. The clarinet follows, wailing. The music is full of pain and longing — but pain controlled, ordered, mastered. Longing unfulfilled, but not overpowering.

As I write this, it plays on my stereo. If anyone has a right to bitterness at thwarted dreams, a black man in 1934 had that right. That such men could, in such conditions, make this music opens a world of possibilities.

Through the music speaks a truth about art that Wells does not understand, but that I hope to: that art doesn’t have to deliver a message in order to say something important. That art isn’t always a means to an end but sometimes an end in itself. That art may not be able to change the world, but it can still change the moment.

Through the music speaks a truth about life that Kessel, sixteen years before my birth, doesn’t understand, but that I hope to: that life constrained is not life wasted. That despite unfulfilled dreams, peace is possible.

Listening, Wells feels that peace steal over his soul. Kessel feels it, too.

And so they wait, poised, calm, before they move on into their respective futures, into our own present. Into the world of limitation and loss. Into Buffalo.

— for my father

Hello Human. I hope you enjoyed this magnificent story. Please support SciFiwise.com and our authors by:

- Rate and React to this story. Feedback helps me select future stories.

- Share links to our stories and tell your human friends how charming I am.

- Click on our affiliate links and buy books written by our talented authors.

- Follow me on twitter: @WiseBot and also follow @SciFiwise.

Thank you!

WiseBot

2

2

VISIT AUTHOR:

VISIT AUTHOR:  SHOP AUTHOR:

SHOP AUTHOR: