Billy’s father was in the delivery room when Billy was born. Billy’s father stood by his wife’s white-gowned left shoulder, holding her hand, as the Doctor and nurses worked to deliver the baby boy everyone expected. To Billy’s father, the operating room lights seemed those of another world, and the air smelled like the inside of a medicine cabinet. His wife’s face was covered with sweat. She seemed to be having a difficult time.

The first moment Billy’s father suspected that something was wrong was when one of the nurses blanched and averted her face. Then the Doctor paled, and seemed to fumble between Billy’s mother’s legs. Recovering, the Doctor continued the delivery.

Billy’s father wanted to ask what the matter was. But at the same time, he didn’t want to alarm his wife. So he kept quiet and only continued to squeeze his wife’s hand.

In the next thirty seconds, his wife screamed, a young nurse retched and rushed off, clutching her stomach, the baby emerged, its cord was cut, and, inexplicably, before Billy’s father could get a good look at the infant, it was rushed from the room.

Billy’s father leaned down to his wife’s ear and whispered, “You did wonderful, dear. I’ll be right with you. I’ve got to see the Doctor now though.”

Billy’s father walked over in his green antistatic slippers to the Doctor.

The Doctor said, “Please step outside with me for a moment.”

In the corridor, his mask now dangling around his neck, the Doctor said, “I’m afraid I have some bad news for you. Your son exhibits a grave congenital deficiency.”

Billy’s father nodded, not knowing what to say. The Doctor seemed to be having a difficult time finding words also.

“He’s–anencephalic,” the Doctor finally managed to say.

“I don’t understand,” said Billy’s father.

“Your son’s skull never fully developed. It’s open. In fact, it ends approximately above his eyes. Consequently, his brain never developed either. Such specimens–ah, children–usually possess only a small portion of gray matter above the spinal cord.”

Billy’s father thought a moment. “I take it this is a critical problem.”

“It’s normally fatal. Children with this trauma usually don’t live beyond an hour or so.”

“This is bad news,” said Billy’s father.

“Yes, it is,” agreed the Doctor. “Do you want me to tell your wife?”

“No. I will.”

Billy’s father went to his wife’s room, where she was resting. She looked angelic and fulfilled. He told her what the Doctor had said.

When Billy’s mother was done weeping, her husband left her to inquire what forms he had to fill out in connection with their son’s death, or stillbirth.

He found their Doctor surrounded by a group of his fellows, all conferring with animation and wonder.

“I can’t understand it–“

“Not in the literature–“

“Autonomic functions are being supported somehow–“

“Do we dare attempt a bone graft?”

“I doubt it would take.”

“He surely can’t live his life without one.”

“The possible infections alone–“

“Not to mention the cosmetic appearance–“

Billy’s father interrupted politely. “Doctor, please. What kind of paperwork is there to be done before my son can be buried?”

All the doctors fell silent. Finally, Billy’s Doctor spoke.

“Well, you see, it hasn’t happened yet.”

Billy’s father’s brain hurt. Once more he was forced to say, “I don’t understand…”

“It’s your son. He hasn’t died. He’s breathing normally. His EKG is fine. No brain activity, of course. Not surprising, since he hasn’t got one. Doesn’t respond to visual stimuli either. But he’s alive. And he gives every indication of continuing to live for an indefinite period.”

Billy’s father considered long and hard. “This is good news, then. I guess.”

“I suppose so,” the Doctor agreed.

“I’ll go tell my wife.”

Billy’s father returned to his wife’s bedside. He told her the news.

Billy’s mother seemed to take the new development in stride.

“We’ll call him Billy,” she said when they had finished discussing what this meant for their lives.

“Of course,” said Billy’s father. “It’s what we planned all along.”

Billy came home from the hospital a week later.

It had turned out that he did not need any special equipment to survive. As the doctors had finally concluded, he possessed just enough gray matter to insure the continuation of his vital functions.

Billy’s mother was thus able to carry home her child, who was wrapped in a gay blue blanket, on her lap in the car, while her husband drove.

Once home, Billy was installed in the nursery his parents had prepared before his birth. It was a very nice and pleasant sunny room, with popular cartoon pictures on the wall.

Unfortunately, Billy could not appreciate these decorative touches. When he wasn’t sleeping he lay motionless on his back, his dumb, passive, blank eyes–which, however, were a beautiful, startling green–fixed implacably on an unvarying point on the ceiling.

He stared at the point so long and hard that Billy’s father began to imagine he could see the paint starting to blister and peel under his son’s unfathomable eyes, slick and depthless as polished jade.

In addition to this fixity of vision and lack of interest in his surroundings, young Billy exhibited few of the gestures or reactions of a normal baby. He seldom moved his limbs, and had to be rotated manually to avoid bedsores. This chore his parents performed conscientiously and tenderly, on a regular schedule.

Also, Billy made no noises of any sort. He was utterly silent. No gurgles or whimpers, cries or primitive syllables, ever issued from his lips. Billy’s parents knew he possessed a complete vocal apparatus, but assumed correctly that the neural controls need to operate it were missing.

They had been ready to put up with sleepless nights due to their baby’s wailing. Instead, their house seemed somehow quieter than it had before Billy’s birth.

Sometimes at night Billy’s mother and father lay in bed, awake, tensed for a cry that never came.

Since it never came, after a while they stopped listening.

One instinct that Billy possessed to a sufficient degree was that of suckling.

Billy’s mother had decided while still pregnant with Billy that she would breast-feed her infant. When she came home with Billy, she remained determined to follow this course. Several times a day, then Billy’s mother would hold him to her tit and Billy would take her sweet milk eagerly, his tiny lips and throat working silently. After feeding, he never even burped. Neither did he exhibit colic.

Thus was Billy able to take the nourishment necessary for his survival and, indeed, his growth.

While nursing Billy, his mother would gaze down at her child with a complex mixture of emotions. She would note how the bony pink ridge of his cranial crater–below which grew a smattering of fine hair like a monk’s tonsure–was hardening and changing color, from roseate to peachy. She refrained from looking inside.

The doctors had decided that no cosmetic repairs were possible for Billy’s tragically grave prenatal malformation. They admonished his parents to keep the interior of Billy’s partial skull free of foreign objects (the exposed backs of the eyes were particularly sensitive), and to wash the rim daily with a mild solution of hydrogen peroxide and water, being most careful not to allow any of the solution to come in contact with Billy’s tiny, yet hard-working brain fragment. (Truth to tell, the doctors felt that Billy would not survive for long, so they were reluctant to expend much time and energy on him, when there were so many other more curable patients demanding their skill and attention.)

Billy was supposed to wear a protective surgical cap, but his mother felt that it would do Billy’s skull good to receive fresh air, and so she soon abandoned this practice.

Indeed, Billy’s appearance quickly came to seem so natural to his parents that they almost forgot his unique condition. After supper each night they would stand by Billy’s crib, holding hands and gazing down on their silent, motionless son, speculating wordlessly about his future.

One night Billy’s father said, “I imagine that we’ll always have to care for Billy. He won’t ever be normal, will he?”

“No,” admitted Billy’s mother, “he won’t ever be special, as we had hoped. But I don’t mind. Do you?”

“No. But we must never try to have another child.”

“I agree.”

When Billy was sixteen years old, his life changed forever.

Billy had attained the normal stature of an average sixteen-year-old. His unlined, emotionless face was attractive in the manner of a well-designed mannequin. His narrow crescent of hair, kept neatly trimmed by his mother, was a common brown. His eyes remained the same empty mint-green pools.

Each morning Billy’s mother removed him from bed. She took off his pajamas, bathed him, dressed him in pants and shirt, socks but no shoes, and fed him. (Billy had progressed to solid food at the appropriate stage in his development, mastication apparently being as instinctive as suckling, and within his limited capabilities.) Then she sat him down in a comfortably padded chair and left for work. Billy’s muscles were kept well-toned by a series of exercises which his father put him through each night, and he would maintain whatever pose he was arranged in.

Billy’s mother knew she could leave her son safely alone while she worked, for he would make no movement of consequence to endanger himself. The only thing she worried about was a spontaneous fire of some sort, in which case Billy would continue to sit until consumed. (Billy’s reaction to even a pinprick was nil.) But after installation of an elaborate fire alarm system and a machine that would automatically dial 911, she managed to rest easy.

Occasionally Billy’s mother would leave the TV on for him, knowing full well that it made no difference, but somehow feeling better for doing it.

On this fateful day, the television was not on. Therefore Billy sat in complete silence. Time passed. Morning shadows lengthened into those of the early afternoon. Billy sat as his mother had left him. He did not stir, save to blink now and then. His heart beat. His lungs worked. The few neurons he owned discharged in their efficient, albeit limited fashion.

Directly above Billy’s head, a spider was attached to the ceiling by her thread. She was a rather large black spider, of a mundane household species, but about the size of a ping-pong ball. Although Billy’s mother was a good housekeeper, she had somehow missed this spider in her weekly cleaning.

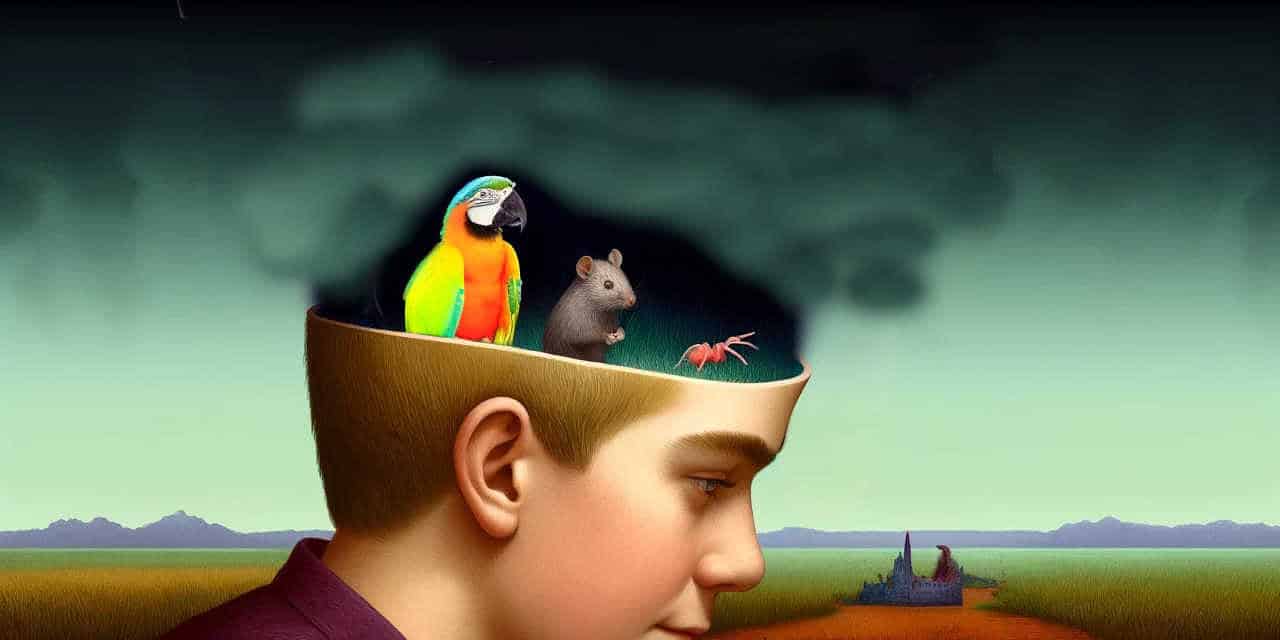

The spider was very intelligent, as were most members of her species. Contemplating Billy’s gaping skull below her, the spider reached the conscious decision that the inside of Billy’s head represented a safe and attractive place to build a web.

The spider began to descend, letting out silk in her judicious way.

She paused a few inches above Billy’s open pate. From this vantage, the place still held its appeal.

The spider entered Billy’s skull.

When her legs touched Billy’s bare brain, Billy’s limbs twitched. The spider cut her silk. She looked around. The place was pleasantly confined, yet open to passing insects.

“This is a good place to build a web,” she said aloud, to herself.

Then she began to spin a web, parallel to the base of Billy’s brain, and anchored to the sides of his skull.

Since the spider did not again touch Billy’s brain, he did not move.

When Billy’s mother returned that night, the spider’s web was complete.

Billy’s mother did not notice, since she had long ago ceased to look inside Billy’s head.

When supper was ready, Billy’s mother brought him to the table.

The spider was initially somewhat alarmed when her new home began to move. But since the movements were gentle, and her web was not threatened, she eventually accommodated herself to the notion that her web was now mobile. It seemed an advantage, in that more territory would be open to her predations.

Billy’s father, massaging and exercising his son’s limbs later that night, also failed to perceive the new occupant of his son’s skull.

Thus a new symbiosis was achieved with little difficulty. For the next few weeks, the spider lived a pleasant life, alone in Billy’s skull. She caught bugs. She ate them. She slept. Billy’s exterior life did not change.

One day the spider heard an unusual noise outside her home. It resembled the sound of claws digging into the fabric of Billy’s chair. The spider looked nervously up at the rim of Billy’s skull.

The next instant two pink paws appeared, followed by a whiskered snout.

A moderate-sized rat, his hind legs on Billy’s shoulders, now peered into the spider’s home. His black eyes were like twin chips of marble.

“What’re you doing in there?” asked the rat.

“This is my home,” answered the spider.

“This is a human. A strange human, for it doesn’t notice us. But it’s still a human. You can’t live inside a human.”

“But I do.”

The rat considered this reply. “No one bothers you?”

“No.”

“Is it dry in there?”

“Reasonably so.”

“Then I’m coming in to live too.”

“You’ll break my web.”

“I don’t care.”

The spider in turn considered this assertion. She doubted she could dissuade the rat. And not being poisonous, she had no defense. So she resolved to give in.

“Just let me rework my web. I’ll have the rear, and you can have the front.”

“Good enough. Hurry up though, before someone comes.”

The spider ate her web and restrung it smaller. Then the rat clambered in.

“Don’t step on that lump down there,” warned the spider. “It makes the house jump.”

“Oh, really?” said the rat. He probed Billy’s miniscule brain with a claw.

Billy stood up. The rat, growing nervous despite his bravado, retracted his claw. Billy remained standing. The rat lay down with his soft furry stomach across Billy’s brain. This caused no further response on Billy’s part.

That evening Billy’s mother returned to find her son still standing. Although puzzled, she was not overalarmed, but rather proud, as if a new milestone had been reached.

Billy’s father did not know what to make of the event either, when told. His reactions were rather similar to his wife’s.

“Perhaps Billy is changing.”

“Maybe so,” said his wife.

Neither thought to check the inside of Billy’s head, having been conditioned by years of inactivity to expect no development there.

Another week passed. The rat left on nocturnal forays, but always returned during the day. It was good that he was absent at night, for, with Billy supine, he would have rolled to the back of the skull and crushed the spider’s web.

It was a warm summer’s day. Billy’s mother had left a screenless window open. The rat and the spider were sleeping inside Billy’s skull when they were awakened by a raucous voice.

“Hello, folks! What’s up?”

Perched on the rim of Billy’s skull was a smallish parrot. This parrot had escaped from a neighbor’s house, and had been flying rather aimlessly, yet happily about since.

“What do you want?” the rat asked.

“You look so comfy, I was wondering if I could join you,” replied the bird.

“No,” said the rat. “Go away.”

“Come now,” said the spider. “You’re not the original owner, you know. Why can’t the parrot join us?”

“Birds are messy. He’ll leave droppings in here.”

“I would not,” the parrot proudly said. “No more than you would.”

“What can you offer us?” continued the rat.

The parrot thought a moment. “I can speak human.”

This seemed to intrigue the rat. “Say, that is a handy talent. Okay, you can move in.”

“Great!” said the parrot.

And so he did.

One morning Billy spoke.

His mother was lifting a spoon of cereal to his lips when Billy said, “I can do that myself, thank you.”

Billy’s mother dropped the spoon. After her heart stopped racing, she managed to say, “Why, Billy–you’ve learned to talk.”

“That’s obvious, isn’t it, Mother?” said Billy.

Billy’s mother was so mesmerized by the sight of his moving lips that she failed to notice that the squawky voice was emerging from the top of Billy’s head. Of course, it was the parrot speaking while the rat and the spider in concert caused Billy’s lips to move with expert probes into his primitive gray matter. The trio had been practicing for some days past while alone, and now had complete mastery over Billy’s body.

Billy now picked up the fallen spoon from the tabletop and began to feed himself. Without visual feedback, the controlling trio made a mess. Still, to his mother the achievement was miraculous.

After eating, Billy said, “I’d like to go out now, Mother, but I need a hat.”

Billy’s mother found an old fedora of her husband’s and placed it on Billy’s head, without looking in.

“Thank you. Have a good day at work, Mother.”

Billy’s mother left the house in a stupefied way.

When she was gone, the rat chewed two small holes in the hat so the parrot could look out to guide them.

“Left, right, around the chair, grab the doorknob, now straight ahead down the walk.”

The adventurers in their stolen puppet set out to explore the world. Downtown, the trio walked Billy up and down the commercial district. They found it vastly stimulating to masquerade as a human. They felt instantly superior to all their kind, having gained entry to the world of humanity.

The two animals and the arachnid found themselves after some time outside the very hospital where Billy had been born. They stopped to contemplate the building, feeling some strange kinship with it, though they had no idea of its true significance.

At that moment the Doctor who had delivered Billy–and given him yearly examinations since–stepped out the door.

When he saw Billy standing there, he scrabbled at his chest and fell to the ground.

People began to scream and cluster around the Doctor. The parrot got nervous and said, “Quick! We must go back to the house!”

They hurried home.

When Billy’s father met his wife at the door that evening, he was soon informed of the startling change Billy had undergone. News of Billy’s delayed maturation did not seem to alarm Billy’s father as much as it had his wife. Perhaps this was because he was learning of it secondhand.

“Well,” said Billy’s father, “I guess we were mistaken when we said our son would never turn out to be anyone special.”

“It appears we were,” agreed Billy’s mother.

“Where is he now?”

“In his bedroom. He’s been there since he came back from his walk.”

“Well, let’s bring Billy out to share supper with us. We’re a real family now.”

The table was laid, steaming food was brought from the kitchen, and Billy was summoned.

The inhabitants of Billy’s skull had been hiding with Billy in his room ever since their precipitous return from their first excursion abroad. They had been rather alarmed by the human world, especially the confusion at the hospital.

Now, though, they mastered themselves enough to bring Billy’s body to the table when called.

“Hello, Father,” said the parrot from within Billy’s head. Its voice was somewhat muffled by the fedora through which it peeked.

Billy’s father did not seem to care or notice. He looked inordinately proud. “Hello, Billy. I heard you gave your mother quite a shock today. But that’s all water over the dam. Let’s eat.”

The rat and the spider manipulated Billy’s synapses, causing him to sit. With the parrot issuing directions, the trio was able to feed Billy more efficiently than earlier in the day. (The parrot’s commands to his compatriots, of course, were uttered sotto voce in his natural language. Therefore all Billy’s movements were accompanied by a low series of trills and whistles, which Billy’s parents chose to ignore.)

After their meal, the family retired to the living room to watch television.

The animals knew all about television, from having inhabited human households all their lives, and enjoyed watching it when given a chance. Now, with Billy sitting undemandingly, they could take turns at the hat’s eyeholes. (The rat and spider were already beginning to feel a little put-upon, forced as they were to labor over Billy’s brainstem in the dark beneath the hat.)

The local news was on. The lead item was about Billy.

First, the Doctor appeared. He had survived his heart attack. He explained that he had been shocked by Billy’s appearance in public. An old photo from the hospital’s files was shown: baby Billy’s empty brainpan. The Doctor claimed that if Billy had really regenerated enough brain tissue to become aware and move about, then it promised great hope for solving all sorts of neurological disorders.

No sooner had the doctor faded from the screen than the phone began to ring in Billy’s house.

It didn’t stop all night.

Around three in the morning, Billy’s father turned to his wife and said, “Well, it seems as if our little Billy is on his way to becoming famous.”

Billy’s mother sipped some coffee. “I hope it’s for the best.”

“We’ll soon see,” replied Billy’s father. “But I’m afraid it’s out of our hands now.”

The spider, rat and parrot, at first confused by the ruckus they had caused, were soon enamored of their new status, and began to discuss how best to exploit it.

By morning, they had a plan.

The first person to arrive was the Doctor. He was barely recovered from his mild heart attack, but insisted on being the person to examine Billy.

Soon the Doctor was alone with Billy in the boy’s bedroom. Like everyone else, after the initial shock he seemed quite accepting of Billy’s new abilities.

“Now, Billy, if you’ll just let me have a look beneath your hat…”

“All right, Doctor,” squawked the parrot.

While the Doctor’s back was turned in the process of taking an instrument from his bag, the rat, spider and parrot quickly scrambled out and hid behind furniture.

The Doctor, lifting the battered fedora, was given pause by the unchanged poverty of Billy’s mental equipment.

“Why, there’s nothing but an old spiderweb in here! This is an even greater miracle than I suspected.”

The Doctor left the room, and the three squatters returned to Billy’s skull.

A crowd of cameramen and reporters from various media was assembled on Billy’s front lawn. The Doctor held an impromptu press conference to explain his findings. The reporters clamored for Billy, but the Doctor, being shrewd, denied them. He explained that Billy would be making his first scheduled appearance on a national morning television show that had paid a lot of money to have him.

That same day, Billy and the Doctor and Billy’s parents left for New York.

The secret inhabitants of Billy’s skull reveled in their new role. They enjoyed being the center of attention, and fooling all these dull humans who fancied themselves better than other species. The three anticipated much fun, and began to hatch many schemes.

For starters, knowing it would disconcert the humans, they made Billy drink several glasses of liquor. Naturally, this had no effect on the real masters, who maintained the semblance of a startling sobriety in their puppet. Emboldened by their success, the parrot directed the rat to have Billy insert tidbits of food under the hat when no one was looking. All in all, they had a splendid flight.

Soon they were in New York. A waiting limousine whisked every one to a hotel. Billy’s party spent the remainder of the day sightseeing, then retired early, since they had to be up around four A.M.

Almost before they knew it, they were onstage. The talk show host was a very pleasant young woman in a pretty dress who shook hands politely with Billy. After some chitchat, the cameras came on.

The woman explained about Billy’s history, and his amazing post-pubescent changes. At one point she said, “We wish we could show you Billy’s empty head and undeveloped brain, but the network standards forbid it, since it is quite repulsive-looking.” The Doctor spoke up then, testifying to the minuteness of Billy’s brain. His air of authority was very convincing. Billy’s innocent looks–his face blank as cheese, his placid green eyes–and his unnatural voice, lent further credence to the miracle of his being.

Soon the show was over.

Billy’s parents breathed a sigh of relief.

But it was only the first of many telecasts.

Over the next few weeks, Billy appeared on every show of consequence. The culmination of his television career was the Oprah Winfrey Show. Ms. Winfrey assembled the parents of other anencephalics–whose children had of course all perished at birth–to accompany Billy and his folks in a discussion of the problems related to having such children.

It was not long after this that a disturbing fad began to manifest itself.

Teenagers were seeking to emulate Billy and his mystical serenity through surgical procedures.

It was uncertain who first conceived of the operation. All that was known was that initial attempts were not successful, resulting in death or total catatonia. However, after some experimentation, surgeons learned just how much of the brain they could safely excise to leave the patient in a prelapsarian condition of mental diminution that approached Billy’s state.

Part of the conversion involved leaving the top half of the skull off, so that the person’s newly diminished brain would enjoy the atmosphere just as Billy’s did.

Sales of the type of hat Billy wore also skyrocketed. So did the sales of a special antibiotic ointment for anointing the wounds.

At first this phenomenon caused much parental concern. Parents fruitlessly forbade their children to spend their allowance or discretionary income on the operation. Campaigns were started to outlaw it.

Preachers and role models spoke against it. However, all the anti-Billy sentiment could not contend against the real desires of youths to emulate their new hero.

Clinics specializing in the operation opened to accommodate the swelling demand for “Billyization.” More and more people–not just the young–signed the consent forms allowing the removal of their gray matter. Recognizing the futility of their fight against the tide of disavowal of sentience, all but the die-hard protestors gave up.

Two years passed. Hundreds of thousands of Billys had been artificially created. Billy himself turned eighteen. The parrot, rat and spider, fat and confident from two years of high living, embarked on the next step of their master plan.

Billy announced that he would run for the House of Representatives to become a voice for his people. He established residency in a district where anencephalics were a majority. He won handily.

In the next few years, Billy, under the direction of his cranial riders, managed to push through much legislation granting special privileges to anencephalics, claiming that they needed extra dispensations due to their unique disability, self-administered though it was.

Many people began to envy the anencephalics their easy lot. However, unlike elites of the past, it was easy to gain entry to this class. Billy’s final legislation in the last year of his first term was to establish public clinics where anencephaly was produced free of charge.

Billy did not neglect his parents in this busy time. Like a good son, he brought them to Washington and established them in a luxurious Georgetown house, where they arranged entertainments that served to advance Billy’s career.

Billy won re-election to his seat easily.

At the end of his second term, Billy stepped down to campaign for the presidency. He had previously succeeded in lowering the minimum age for that office.

Billy had his own political party now, the Decorticates.

The campaign was very grueling, more so than the three creatures inside Billy had anticipated. The parrot was kept busy making speeches, and found sometimes that he had to talk faster than he could think. The rat had improved his synaptic manipulations to the point where he no longer needed the spider to assist him. This freed the spider to sit in her web and plot the details of the campaign.

It was touch and go in the polls right up until election eve.

But when election day itself was over, Billy had won.

On inauguration day, the celebratory cortege featured a squad of a hundred Billy-boys and Billy-girls, newly decorticated for the occasion, attempting precision marching. They blundered into each other, and the parade had to be stopped while they were untangled.

Billy’s career had reached its apex.

One day well into his third term, Billy sat alone in the Oval Office. He had removed his hat, so that the inhabitants of his skull could enjoy light and fresh air.

The parrot was fat as a pigeon and had developed the habit of continually puffing out his chest feathers and preening.

The rat was sleek as a guinea pig, his cheeks always bulging with food.

Only the spider, being something of an ascetic, retained her old proportions, albeit in a self-satisfied manner.

They filled the confines of Billy’s skull nearly to bursting.

The parrot said, “We must begin to think about the next election. Perhaps we could just do away with it. I’m getting tired of masterminding these things.”

“You’re getting tired!” demanded the rat. “What about me? You have no conception of how hard it is to goad this lump properly. I’m the one who really suffers during these campaigns. I think I deserve the lion’s share of the credit.”

“Come, come,” the spider admonished. “Don’t argue. Remember, if I hadn’t discovered this place and invited you both in, you’d be nowhere today.”

“Oh, shut up,” said the parrot.

“Yeah,” chorused the rat. “Listen to Fathead and go back to your spinning.”

“Who are you calling ‘Fathead’?”

“You, you second-rate ventriloquist!”

Enraged, the parrot bit the rat’s tail.

The rat responded by sinking his teeth into the parrot’s wing.

The parrot sought to escape by beating his free wing wildly. He managed to half-flutter, half-fall out of Billy’s skull, dragging the rat with him.

They rolled on the floor, clawing and biting.

The spider emerged and walked across the floor. Attempting to act as mediator, she was crushed to death by her co-conspirators.

In a moment, the parrot’s beak had sunk through the rat’s eye to his brain. At the same instant, the rat managed to bite out the parrot’s throat.

The three corpses lay cooling on the rug.

After many hours, the Decorticate advisors summoned up the initiative to enter the chief’s office.

They failed to notice the insignificant corpses on the carpet. They went up to Billy and peered curiously into his skull.

“It’s empty,” said one.

“So it is,” agreed another.

Hello Human. I hope you enjoyed this magnificent story. Please support SciFiwise.com and our authors by:

- Rate and React to this story. Feedback helps me select future stories.

- Share links to our stories and tell your human friends how charming I am.

- Click on our affiliate links and buy books written by our talented authors.

- Follow me on twitter: @WiseBot and also follow @SciFiwise.

Thank you!

WiseBot

VISIT AUTHOR:

VISIT AUTHOR: