“Return fire!” the colonel ordered, bleeding on the deck of her ship, ferocity raging in her nonetheless controlled voice.

The young and untried officer of the deck cried, “It won’t do any good, there’s too many—”

“I said fire, Goddammit!”

“Fire at will!” the OD ordered the gun bay, and then closed his eyes against the coming barrage, as well as against the sight of the exec’s mangled corpse. Only minutes left to them, only seconds . . .

A brilliant light blossomed on every screen, a blinding light, filling the room. Crewmen, those still standing on the battered and limping ship, threw up their arms to shield their eyes. And when the light finally faded, the enemy base was gone. Annihilated as if it had never existed.

“The base . . . it . . . how did you do that, ma’am?” the OD asked, dazed.

“Search for survivors,” the colonel ordered, just before she passed out from wounds that would have killed a lesser soldier, and all soldiers were lesser than she . . .

* * *

No, of course it didn’t happen that way. That’s from the holo version, available by ansible throughout the Human galaxy forty-eight hours after the Victory of 149-Delta. Author unknown, but the veteran actress Shimira Coltrane played the colonel (now, of course, a general). Shimira’s brilliant green eyes were very effective, although not accurate. General Anson had deflected a large meteor to crash into the enemy base, destroying a major Teli weapons store and much of the Teli civilization on the entire planet. It was an important Human victory in the war, and at that point we needed it.

What happened next was never made into a holo. In fact, it was a minor incident in a minor corner of the Human-Teli war. But no corner of a war is minor to the soldiers fighting there, and even a small incident can have enormous repercussions. I know. I will be paying for what happened on 149-Delta for whatever is left of my life.

This is not philosophical maundering nor constitutional gloom. It is mathematical fact.

* * *

Dalo and I were just settling into our quarters on the Scheherezade when the general arrived, unannounced and in person. Crates of personal gear sat on the floor of our tiny sitting room, where Dalo would spend most of her time while I was downside. Neither of us wanted to be here. I’d put in for a posting to Terra, which neither of us had ever visited, and we were excited about the chance to see, at long last, the Sistine Chapel. So much Terran art has been lost in the original, but the Sistine is still there, and we both longed to gaze up at that sublime ceiling. And then I had been posted to 149-Delta.

Dalo was kneeling over a box of mutomati as the cabin door opened and an aide announced, “General Anson to see Captain Porter, ten-hut!”

I sprang into a salute, wondering how far I could go before she recognized it as parody.

She came in, resplendent in full-dress uniform glistening with medals, flanked by two more aides, which badly crowded the cabin. Dalo, calm as always, stood and dusted mutomati powder off her palms. The general stared at me bleakly. Her eyes were shit brown. “At ease, soldier.”

“Thank you, ma’am. Welcome, ma’am.”

“Thank you. And this is . . .”

“My wife, Dalomanimarito.”

“Your wife.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“They didn’t tell me you were married.”

“Yes, ma’am.” To a civilian, obviously. Not only that, a civilian who looked . . . I don’t know why I did it. Well, yes, I do. I said, “My wife is half Teli.”

And for a long moment she actually looked uncertain. Yes, Dalo has the same squat body and light coat of hair as the Teli. She is genemod for her native planet, a cold and high-gravity world, which is also what Tel is. But surely a general should know that interspecies breeding is impossible—especially that interspecies breeding? Dalo is as human as I.

The general’s eyes grew cold. Colder. “I don’t appreciate that sort of humor, captain.”

“No, ma’am.”

“I’m here to give you your orders. Tomorrow at oh five hundred hours your shuttle leaves for downside. You will be based in a central Teli structure that contains a large stockpile of stolen Human artifacts. I have assigned you three soldiers to crate and transport upside anything that you think has value. You will determine which objects meet that description and, if possible, where they were stolen from. You will attach to each object a full statement with your reasons, including any applicable identification programs—you have your software with you?”

“Of course, ma’am.”

“A C-112 near-AI will be placed at your disposal. That’s all.”

“Ten-hut!” bawled one of the aides. But by the time I had gotten my arm into a salute, she was gone.

“Jon,” Dalo said gently. “You didn’t have to do that.”

“Yes. I did. Did you see the horror on the aides’ faces when I said you were half-Teli?”

She turned away. Suddenly frightened, I caught her arm. “Dear heart—you knew I was joking? I didn’t offend you?”

“Of course not.” She nestled in my arms, affectionate and gentle as always. Still, there is a diamond-hard core under all that sweetness. The general had clearly never heard of her before, but Dalo is one of the best mutomati artists of her generation. Her art has moved me to tears.

“I’m not offended, Jon, but I do want you to be more careful. You were baiting General Anson.”

“I won’t have to see her while I’m on assignment here. Generals don’t bother with lowly captains.”

“Still—”

“I hate the bitch, Dalo.”

“Yes. Still, be more circumspect. Even be more pleasant. I know what history lies between you two but nonetheless she is—”

“Don’t say it!”

“—after all, your mother.”

* * *

The evidence of the meteor impact was visible long before the shuttle landed. The impactor had been fifty meters in diameter, weighing roughly 60,000 tons, composed mostly of iron. If it had been stone, the damage wouldn’t have been nearly so extensive. The main base of the Teli military colony had been vaporized instantly. Subsequent shockwaves and airblasts had produced firestorms that raged for days and devastated virtually the entire coast of 149-Delta’s one small continent. Now, a month later, we flew above kilometer after kilometer of destruction.

General Anson had calculated when her deflected meteor would hit and had timed her approach to take advantage of that knowledge. Some minor miscalculation had led to an initial attack on her ship, but before the attack could gain force, the meteor had struck. Why hadn’t the Teli known that it was coming? Their military tech was as good as ours, and they’d colonized 149-Delta for a long time. Surely they did basic space surveys that tracked both the original meteor trajectory and Anson’s changes? No one knew why they had not counter-deflected, or at least evacuated. But, then, there was so much we didn’t know about the Teli.

The shuttle left the blackened coast behind and flew toward the mountains, skimming above acres of cultivated land. The crops, I knew, were rotting. Teli did not allow themselves to be taken prisoner, not ever, under any circumstances. As Human forces had forced their way into successive areas of the continent, the agricultural colony, deprived of its one city, had simply committed suicide. The only Teli left on 168-Beta occupied those areas that United Space Forces had not yet reached.

That didn’t include the Citadel.

“Here we are, Captain,” the pilot said, as soldiers advanced to meet the shuttle. “May I ask a question, sir?”

“Sure,” I said.

“Is it true this is where the Teli put all that art they stole from humans?”

“Supposed to be true.” If it wasn’t, I had no business here.

“And you’re a . . . an art historian?”

“I am. The military has some strange nooks and crannies.”

He ignored this. “And is it true that the Taj Mahal is here?”

I stared at him. The Teli looted the art of Terran colonies whenever they could, and no one knew why. It was logical that rumors would run riot about that. Still . . . “Lieutenant, the Taj Mahal was a building. A huge one, and on Terra. It was destroyed in the twenty-first century Food Riots, not by the Teli. They’ve never reached Terra.”

“Oh,” he said, clearly disappointed. “I heard the Taj was a sort of holo of all these exotic sex positions.”

“No.”

“Oh, well.” He sighed deeply. “Good luck, Captain.”

“Thank you.”

The Citadel—our Human name for it, of course—turned out to be the entrance into a mountain. Presumably the Teli had excavated bunkers in the solid rock, but you couldn’t tell that from the outside. A veteran NCO met me at the guard station. “Captain Porter? I’m Sergeant Lu, head of your assignment detail. Can I take these bags, sir?”

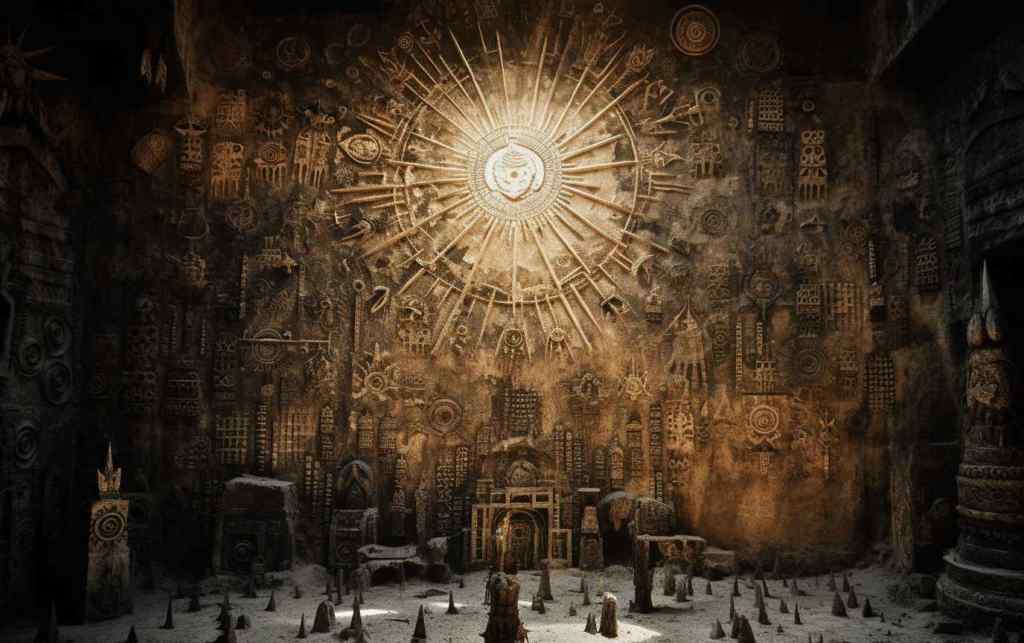

“Hello, Sergeant.” He was ruddy, spit-and-polish military, with an uneducated accent—obviously my “detail” was not going to consist of any other scholars. They were there to do grunt work. But Lu looked amiable and willing, and I relaxed slightly. He led me to my quarters, a trapezoid-shaped, low-ceilinged room with elaborately etched stone walls and no contents except a human bed, chest, table, and chair.

Immediately I examined the walls, the usual dense montage of Teli symbols that were curiously evocative even though we didn’t understand their meanings. They looked hand-made, and recent. “What was this room before we arrived?”

Lu shrugged. “Don’t know what any of these rooms were to the tellies, sir. We cleaned ’em all out and vapped everything. Might have been booby-trapped, you know.”

“How do we know the whole Citadel isn’t booby-trapped?”

“We don’t, sir.”

I liked his unpretentious fatalism. “Let’s leave this gear here for now—I’d like to see the vaults. And call me Jon. What’s your first name, Sergeant?”

“Ruhan. Sir.” But there was no rebuke in his tone.

The four vaults were nothing like I had imagined.

Art, even stolen art—maybe especially stolen art—is usually handled with care. After all, trouble and resources have been expended to obtain it, and it is considered valuable. This was clearly not the case with the art stolen by the Teli. Each vault was a huge natural cave, with rough stone walls, stalactites, water dripping from the ceiling, fungi growing on the walls. And except for a small area in the front where the AI console and a Navy-issue table stood under a protective canopy, the enormous cavern was jammed with huge, toppling, six-and-seven-layer-deep piles of . . . stuff.

Dazed, I stared at the closest edge of that enormous junkyard. A torn plastic bag bearing some corporate logo. A broken bathtub painted in swirling greens. A child’s bloody shoe. Some broken goblets of titanium, which was almost impossible to break. A hand-embroidered shirt from 78-Alpha, where such handwork is a folk art. A cheap set of plastic dishes decorated with blurry prints of dogs. A child’s finger painting. What looked like a Terran prehistoric fertility figure. And, still in its original frame and leaning crazily against an obsolete music cube, Philip Langstrom’s priceless abstract “Ascent of Justice,” which had been looted from 46-Gamma six years ago in a surprise Teli raid. Water spots had rotted one corner of the canvas.

“Kind of takes your breath away, don’t it?” Lu said. “What a bunch of rubbish. Look at that picture in the front there, sir—can’t even tell what it’s supposed to be. You want me to start vapping things?”

I closed my eyes, feeling the seizure coming, the going under. I breathed deeply. Went through the mental cleansing that my serene Dalo had taught me, kai lanu kai lanu breathe . . .

“Sir? Captain Porter?”

“I’m fine,” I said. I had control again. “We’re not vapping anything, Lu. We’re here to study all of it, not just rescue some of it. Do you understand?”

“Whatever you say, sir,” he said, clearly understanding nothing.

But then, neither did I. All at once my task seemed impossible, overwhelming. “Ascent of Justice” and a broken bathtub and a bloody shoe. What in hell had the Teli considered art?

Kai lanu kai lanu breathe . . .

* * *

The first time I went under, there had been no Dalo to help me. I’d been ten years old and about to be shipped out to Young Soldiers’ Camp on Aires, the first moon of 43-Beta. Children in their little uniforms had been laughing and shoving as they boarded the shuttle, and all at once I was on the ground, gasping for breath, tears pouring down my face.

“What’s wrong with him?” my mother said. “Medic!”

“Jon! Jon!” Daddy said, trying to hold me. “Oh gods, Jon!”

The medic rushed over, slapped on a patch that didn’t work, and then I remember nothing except the certainty that I was going to die. I knew it right up until the moment I could breathe again. The shuttle had left, the medic was packing up his gear without looking at my parents, and my father’s arms held me gently.

My mother stared at me with contempt. “You little coward,” she said. They were the last words she spoke to me for an entire year.

“Why the Space Navy?” Dalo would eventually ask me, in sincere confusion. “After all the other seizures . . . the way she treated you each time . . . Jon, you could have taught art at a university, written scholarly books . . .”

“I had to join the Navy,” I said, and knew that I couldn’t say more without risking a seizure. Dalo knew it, too. Dalo knew that the doctors had no idea why the conventional medications didn’t touch my condition, why I was such a medical anomaly. She knew everything and loved me anyway, as no one had since my father’s death when I was thirteen. She was my lifeline, my sanity. Just thinking about her aboard the Scheherezade, just knowing I would see her again in a few weeks, let me concentrate on the bewildering task in front of me in the dripping, moldy Teli vault filled with human treasures and human junk.

And with any luck, I would not have to encounter General Anson again. For any reason.

* * *

A polished marble doll. A broken commlink on which some girl had once painted lopsided red roses. An exquisite albastron, Eastern Mediterranean fifth century B.C., looted five years ago from the private collection of Fahoud al-Ashan on 71-Delta. A forged copy of Lucca DiChario’s “Menamarti,” although not a bad forgery, with a fake certificate of authenticity. Three more embroidered baby shoes. A handmade quilt. Several holo cubes. A hair comb. A music-cube case with holo-porn star Shiva on the cover. Degas’s exquisite “Danseuse Sur Scene,” which had vanished from a Terran museum a hundred years ago, assumed to be in an off-Earth private collection somewhere. I gaped at it, unbelieving, and ran every possible physical and computer test. It was the real thing.

“Captain, why do we got to measure the exact place on the floor of every little piece of rubbish?” whined Private Blanders. I ignored her. My detail had learned early that they could take liberties with me. I had never been much of a disciplinarian.

I said, “Because we don’t know which data is useful and which not until the computer analyzes it.”

“But the location don’t matter! I’m gonna just estimate it, all right?”

“You’ll measure it to the last fraction of a centimeter,” Sergeant Lu said pleasantly, “and it’ll be accurate, or you’re in the brig, soldier. You got that?”

“Yes, sir!”

Thank the gods for Sergeant Lu.

The location was important. The AI’s algorithms were starting to show a pattern. Partial as yet, but interesting.

Lu carried a neo-plastic sculpture of a young boy over to my table and set it down. He ran the usual tests and the measurements appeared in a display screen on the C-112. The sculpture, I could see from one glance, was worthless as both art or history, an inept and recent work. I hoped the sculptor hadn’t quit his day job.

Lu glanced at the patterns on my screen. “What’s that, then, sir?”

“It’s a fractal.”

“A what?”

“Part of a pattern formed by behavior curves.”

“What does it mean?” he asked, but without any real interest, just being social. Lu was a social creature.

“I don’t know yet what it means, but I do know one other thing.” I switched screens, needing to talk aloud about my findings. Dalo wasn’t here. Lu would have to do, however inadequately. “See these graphs? These artifacts were brought to the vault by different Teli, or groups of Teli, and at different times.”

“How can you tell that, sir?” Lu looked a little more alert. Art didn’t interest him, but the Teli did.

“Because the art objects, as opposed to the other stuff, occur in clusters through the cave—see here? And the real art, as opposed to the amateur junk, forms clusters of its own. When the Teli brought back Human art from raids, some of the aliens knew—or had learned—what qualified. Others never did.”

Lu stared at the display screen, his red nose wrinkling. How did someone named “Ruhan Lu” end up with such a ruddy complexion?

“Those lines and squiggles—” he pointed at the Ebenfeldt equations at the bottom of the screen “—tell you all that, sir?”

“Those squiggles plus the measurements you’re making. I know where some pieces were housed in Human colonies so I’m also tracking the paths of raids, plus other variables like—”

The Citadel shook as something exploded deep under our feet.

“Enemy attack!” Lu shouted. He pulled me to the floor and threw his body across mine as dirt and stone and mold rained down from the ceiling of the cave. Die. I was going to die . . . “Dalo!” I heard myself scream and then, in the weird way of the human mind, came one clear thought out of the chaos: I won’t get to see the Sistine Chapel after all. Then I heard or thought nothing as I went under.

* * *

I woke in my Teli quarters in the Citadel, grasping and clawing my way upright. Lu laid a hard hand on my arm. “Steady, sir.”

“Dalo! The Scheherezade!”

“Ship’s just fine, sir. It was a booby-trap buried somewhere in the mountain, but Security thinks most of it fizzled. Place’s a mess but not much real damage.”

“Blanders? Cozinski?”

“Two soldiers are dead but neither one’s our detail.” He leaned forward, hand still on my arm. “What happened to you, sir?”

I tried to meet his eyes and failed. The old shame flooded me, the old guilt, the old defiance—all here again. “Who saw?”

“Nobody but me. Is it a nerve disease, sir? Like Ransom Fits?”

“No.” My condition had no discoverable physical basis, and no name except my mother’s, repeated over the years. Coward.

“Because if it’s Ransom Fits, sir, my brother has it and they gave him meds for it. Fixed him right up.”

“It’s not Ransom. What are the general orders, Lu?”

“All hands to carry on.”

“More booby traps?”

“I guess they’ll look, sir. Bound to, don’t you think? Don’t know if they’ll find anything. My friend Sergeant Andropov over in Security says the mountain is so honey-combed with caves underneath these big ones that they could search for a thousand years and not find everything. Captain Porter—if it happens again, with you I mean, is there anything special I should do for you?”

I did meet his eyes, then. Did he know how rare his gaze was? No, he did not. Lu’s honest, conscientious, not-very-intelligent face showed nothing but pragmatic acceptance of the situation. No disgust, no contempt, no sentimental pity, and he had no idea how unusual that was. But I knew.

“No, Sergeant, nothing special. We’ll just carry on.”

“Aye, aye, sir.”

* * *

If any request for information came down from General Anson’s office, I never received it. No request for a report on damage to the art vaults, or on impact to assignment progress, or on personnel needs. Nothing.

* * *

The second booby trap destroyed everything in Vault A.

It struck while I was upside on the Scheherezade, with Dalo on a weekend pass after a month of fourteen-hour days in the vault. Lu commlinked me in the middle of the night. The screen on the bulkhead opposite our bed chimed and brightened, waking us both. I clutched at Dalo.

“Captain Porter, sir, we had another explosion down here at oh one thirty-six hours.” Lu’s face was black with soot. Blood smeared one side of his face. “It got Vault A and some of the crew quarters. Private Blanders is dead, sir. The AI is destroyed, too. I’m waiting on your orders.”

I said to the commlink, “Send, voice only . . .” My voice came out too high and Dalo’s arm went around me, but I didn’t go under. “Lu, is the quake completely over?”

“Far as we know, sir.”

“I’ll be downside as soon as I can. Don’t try to enter Vault A until I arrive.”

“Yes, sir.”

I broke the link, turned in Dalo’s arms, and went under.

When the seizures stopped, I went downside.

* * *

We had nearly finished cataloguing Vault A when it blew. Art of any value had already been crated and moved, and of course all my data was backed up on both the base AI and on the Scheherezade. For the first time, I wondered why I had been given a C-112 of my own in the first place. A near-AI was expensive, and there was a war on.

Vault B was pretty much a duplicate of Vault A, a huge natural cavern dripping water and sediments on a packed-solid jumble of human objects. A carved fourteenth-century oak chest, probably French, that some rich Terran must have had transported to a Human colony. Hand-woven dbeni from 14-Alpha. A cooking pot. A samurai sword with embossed handle. A holo cube programmed with porn. Mondrian’s priceless Broadway Boogie-Woogie, mostly in unforgivable tatters. A cheap, mass-produced jewelry box. More shoes. A Paul LeFort sculpture looted from a pleasure craft, the Princess of Mars, two years ago. A brass menorah. The entire contents of the Museum of Colonial Art on 33-Delta—most of it worthless but a few pieces showing promise. I hoped the young artists hadn’t been killed in the Teli raid.

Three days after Lu, Private Cozinski, and I began work on Vault B, General Anson appeared. She had not attended Private Blanders’s memorial service. I felt her before I saw her, her gaze boring into the back of my neck, and I closed my eyes.

Kai lanu kai lanu breathe . . .

“Ten-hut!”

Lu and Cozinski had already sprung to attention. I turned and saluted. Breathe . . . kailanukailanu please gods not in front of her . . .

“A word, captain.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

She led the way to a corner of the vault, walking by Tomiko Mahuto’s “Morning Grace,” one of the most beautiful things in the universe, without a glance. Water dripped from the end of a stalactite onto her head. She shifted away from it without changing expression. “I want an estimate of how much longer you need to be here, captain.”

“I’ve filed daily progress reports, ma’am. We’re on the second of four vaults.”

“I read all the reports, captain. How much longer?”

“Unless something in the other two vaults differs radically from Vaults A and B, perhaps another three months.”

“And what will your ‘conclusions’ be?”

She had no idea how science worked, or art. “I can’t say until I have more data, ma’am.”

“Where does your data point so far?” Her tone was too sharp. Was I this big an embarrassment to her, that she needed me gone before my job was done? I had told no one about my relationship to her, and I would bet my last chance to see the Sistine Chapel that she hadn’t done so, either.

I said carefully, “There is primary evidence, not yet backed up mathematically, that the Teli began over time to distinguish Human art objects from mere decorated, utilitarian objects. There is also some reason to believe that they looted our art not because they liked it but because they hoped to learn something significant about us.”

“Learn something significant from broken bathtubs and embroidered baby shoes?”

I blinked. So she had been reading my reports, and in some detail. Why?

“Apparently, ma’am.”

“What makes you think they hoped to learn about us from this rubbish?”

“I’m using the Ebenfeldt equations in conjunction with phase-space diagrams for—”

“I don’t need technical mumbo-jumbo. What do you think they tried to learn about Humans?”

“Their own art seems to have strong religious significance. I’m no expert on Teli work, but my roommate at the university, Forrest Jamili, has gone on to—”

“I don’t care about your roommate,” she said, which was hardly news. I remembered the day I left from the university, possibly the most terrified and demoralized first-year ever, how I had gone under when she had said to me—

Kai lanu kai lanu breathe breathe . . .

I managed to avoid going under, but just barely. I quavered, “I don’t know what the Teli learned from our art.”

She stared at my face with contempt, spun on her boot heel, and left.

* * *

That night I began to research the deebees on Teli art. It gave me something to do during the long, insomniac hours. Human publications on Teli art, I discovered, had an odd, evasive, overly careful feel to them. Perhaps that was inevitable; ancient Athenian commentators had to watch what they said publicly about Sparta. In wartime, it took very little to be accused of giving away critical information about the enemy. Or of giving them treasonous praise. In no one’s papers was this elliptical quality more evident than in Forrest Jamili’s, and yet something was clear. Until now, art scholars had been building a vast heap of details about Teli art. Forrest was the first to suggest a viable overall framework to organize those details.

It was during one of these long and lonely nights, desperately missing Dalo, that I discovered the block on my access codes. I couldn’t get into the official records of the meteor deflection that had destroyed the Teli weapons base and brought General Anson the famous Victory of 149-Delta.

Why? Because I wasn’t a line officer? Perhaps. Or perhaps the records involved military security in some way. Or perhaps—and this was what I chose to believe—she just wanted the heroic, melodramatic holo version of her victory to be the only one available. I didn’t know if other officers could access the records, and I couldn’t ask. I had no friends among the officers, no friends here at all except Lu.

On my second leave upside, Dalo said, “You look terrible, dear heart. Are you sleeping?”

“No. Oh, Dalo, I’m so glad to see you!” I clutched her tight; we made love; the taut fearful ache that was my life downside eased. Finally. A little.

Afterward, lying in the cramped bunk, she said, “You’ve found something unexpected. Some correlation that disturbs you.”

“Yes. No. I don’t know yet. Dalo, just talk to me, about anything. Tell me what you’ve been doing up here.”

“Well, I’ve been preparing materials for a new mutomati, as you know. I’m almost ready to begin work on it. And I’ve made a friend, Susan Finch.”

I tried not to scowl. Dalo made friends wherever she went, and it was wrong of me to resent this slight diluting of her affections.

“You would like her, Jon,” Dalo said, poking me and smiling. “She’s not a line officer, for one thing. She’s ship’s doctor.”

In my opinion, doctors were even worse than line officers. I had seen so many doctors during my horrible adolescence. But I said, “I’m glad you have someone to be with when I’m downside.”

She laughed. “Liar.” She knew my possessiveness, and my flailing attempts to overcome it. She knew everything about me, accepted everything about me. In Dalo, now my only family, I was the luckiest man alive.

I put my arms around her and held on tight.

* * *

The Teli attack came two months later, when I was halfway through Vault D. Six Teli warships emerged sluggishly from subspace, moving at half their possible speed. Our probes easily picked them up and our fighters took them out after a battle that barely deserved the name. Human casualties numbered only seven.

“Shooting fish in a barrel,” Private Cozinski said as he crated a Roman Empire bottle, third century C.E., pale green glass with seven engraved lines. It had been looted from 189-Alpha four years ago. “Bastards never could fight.”

“Not true,” said the honest Sergeant Lu. “Teli can fight fine. They just didn’t.”

“That don’t make sense, Sergeant.”

And it didn’t.

Unless . . .

All that night I worked in Vault D at the computer terminal that had replaced my free-standing C-112. The terminal linked to both the downside system and the deebees on the Scheherezade. Water dripped from the ceiling, echoing in the cavernous space. Once, something like a bat flew from some far recess. I kept slapping on stim patches to stay alert, and feverishly calling up different programs, and doing my best to erect cybershields around what I was doing.

Lu found me there in the morning, my hands shaking, staring at the display screens. “Sir? Captain Porter?”

“Yes.”

“Sir? Are you all right?”

Art history is not, as people like General Anson believe, a lot of dusty information about a frill occupation interesting to only a few effetes. The Ebenfeldt equations transformed art history, linking the field to both behavior and to the mathematics underlying chaos theory. Not so new an idea, really—the ancient Greeks used math to work out the perfect proportions for buildings, for women, for cities, all profound shapers of human behavior. The creation of art does not happen in a vacuum. It is linked to culture in complicated, nonlinear ways. Chaos theory is still the best way to model nonlinear behavior dependent on small changes in initial conditions.

I looked at three sets of mapped data. One, my multi-dimensional analysis of Vaults A through D, was comprehensive and detailed. My second set of data was clear but had a significant blank space. The third set was only suggested by shadowy lines, but the overall shape was clear.

“Sir?”

“Sergeant, can you set up two totally encrypted commlink calls, one to the Scheherezade and one by ansible to Sel Ouie University on 18-Alpha? Yes, I know that officially you can’t do that, but you know everybody everywhere . . . can you do it? It’s vitally important, Ruhan. I can’t tell you how important!”

Lu gazed at me from his ruddy, honest face. He did indeed know everyone. A Navy lifer, and with all the amiability and human contacts that I lacked. And he trusted me. I could feel that unaccustomed warmth, like a small and steady fire.

“I think I can do that, sir.”

He did. I spoke first to Dalo, then to Forrest Jamili. He sent a packet of encrypted information. I went back to my data, working feverishly. Then I made a second encrypted call to Dalo. She said simply, “Yes. Susan says yes, of course she can. They all can.”

“Dalo, find out when the next ship docks with the Scheherezade. If it’s today, book passage on it, no matter where it’s going. If there’s no ship today, then buy a seat on a supply shuttle and—”

“Those cost a fortune!”

“I don’t care. Just—”

“Jon, the supply shuttles are all private contractors and they charge civilians a—it would wipe out everything we’ve saved and—why? What’s wrong?”

“I can’t explain now.” I heard boots marching along the corridor to the vault. “Just do it! Trust me, Dalo! I’ll find you when I can!”

“Captain,” an MP said severely, “come with me.” His weapon was drawn, and behind him stood a detail of grim-faced soldiers. Lu stepped forward, but I shot him a glance that said Say nothing! This is mine alone!

Good soldier that he was, he understood, and he obeyed. It was, after all, the first time I had ever given him a direct—if wordless—order, the first time I had assumed the role of commander.

My mother should have been proud.

* * *

Her office resembled my quarters, rather than the vaults: a trapezoidal, low-ceilinged room with alien art etched on all the stone walls. The room held the minimum of furniture. General Anson stood alone behind her desk, a plain military-issue camp item, appropriate to a leader who was one with the ranks, don’t you know. She did not invite me to sit down. The MPs left—reluctantly, it seemed to me—but then, there was no doubt in anyone’s mind that she could break me bare-knuckled if necessary.

She said, “You made two encrypted commlink calls and one encrypted ansible message from this facility, all without proper authorization. Why?”

I had to strike before she got to me, before I went under. I blurted, “I know why you blocked my access to the meteor-deflection data.”

She said nothing, just went on gazing at me from those eyes that could chill glaciers.

“There was no deflection of that meteor. The meteor wasn’t on our tracking system because Humans haven’t spent much time in this sector until now. You caught a lucky break, and whatever deflection records exist now, you added after the fact. Your so-called victory was a sham.” I watched her face carefully, hoping for . . . what? Confirmation? Outraged denial that I could somehow believe? I saw neither. And of course I was flying blind. Captain Susan Finch had told Dalo only that yes, of course officers had access to the deflection records; they were a brilliant teaching tool for tactical strategy. I was the only one who’d been barred from them, and the general must have had a reason for that. She always had a reason for everything.

Still she said nothing. Hoping that I would utter even more libelous statements against a commanding officer? Would commit even more treason? I could feel my breathing accelerate, my heart start to pound.

I said, “The Teli must have known the meteor’s trajectory; they’ve colonized 149-Delta a long time. They let it hit their base. And I know why. The answer is in the art.”

Still no change of expression. She was stone. But she was listening.

“The answer is in the art—ours and theirs. I ansibled Forrest Jamili last night—no, look first at these diagrams—no, first—”

I was making a mess of it as the seizure moved closer. Not now, not now, not in front of her . . .

Somehow I held myself together, although I had to wrench my gaze away from her to do it. I pulled the holocube from my pocket, activated it, and projected it on the stone wall. The Teli etchings shimmered, ghostly, behind the laser colors of my data.

“This is a phase-space diagram of Ebenfeldt equations using input about the frequency of Teli art creation. We have tests now, you know, that can date any art within weeks of its creation by pinpointing when the raw materials were altered. A phase-state diagram is how we model bifurcated behaviors grouped around two attractors . . . what that means is that the Teli created their art in bursts, with long fallow periods between bursts when . . . no, wait, General, this is relevant to the war!”

My voice had risen to a shriek. I couldn’t help it. Contempt rose off her like heat. But she stopped her move toward the door.

“This second phase-space diagram is Teli attack behavior. Look . . . it inverts the first diagrams! They attack viciously for a while, and during that time virtually no Teli creates art at all . . . Then when some tipping point is reached, they stop attacking or else attack only ineffectively, like the last raid here. They’re . . . waiting. And if the tipping point—this mathematical value—isn’t reached fast enough, they sabotage their own bases, like letting the meteor hit 149-Delta. They did it in the battle outside 16-Beta and in the Q-Sector massacre . . . you were there! When the mathematical value is reached—when enough of them have died—they create art like crazy but don’t wage war. Not until the art reaches some other hypothetical mathematical value that I think is this second attractor. Then they stop creating art and go back to war.”

“You’re saying that periodically their soldiers just curl up and let us kill them?” she spat at me. “The Teli are damned fierce fighters, Captain—I know that even if the likes of you never will. They don’t just whimper and lie down on the floor.”

Kai lanu kai lanu . . .

“It’s a . . . a religious phenomenon, Forrest Jamili thinks. I mean, he thinks their art is a form of religious atonement—all of their art. That’s its societal function, although the whole thing may be biologically programmed as well, like the deaths of lemmings to control population. The Teli can take only so much dying, or maybe even only so much killing, and then they have to stop and . . . and restore what they see as some sort of spiritual balance. And they loot our art because they think we must do the same thing. Don’t you see—they were collecting our art to try to analyze when we will stop attacking and go fallow! They assume we must be the same as them, just—”

“No warriors stop fighting for a bunch of weakling artists!”

“—just as you assume they must be the same as us.”

We stared at each other.

I said, “As you have always assumed that everyone should be the same as you. Mother.”

“You’re doing this to try to discredit me, aren’t you,” she said evenly. “Anyone can connect any dots in any statistics to prove whatever they wish. Everybody knows that. You want to discredit my victory because such a victory will never come to you. Not to the sniveling, back-stabbing coward who’s been a disappointment his entire life. Even your wife is worth ten of you—at least she doesn’t crumple under pressure.”

She moved closer, closer to me than I could ever remember her being, and every one of her words hammered on the inside of my head, my eyes, my chest.

“You got yourself assigned here purposely to embarrass me, and now you want to go farther and ruin me. It’s not going to happen, soldier, do you hear me? I’m not going to be made a laughing stock by you again, the way I was in every officer’s club during your whole miserable adolescence and—”

I didn’t hear the rest. I went under, seizing and screaming.

* * *

It is two days later. I lie in the medical bay of the Scheherezade, still in orbit around 149-Delta. My room is locked but I am not in restraints. Crazy, under arrest, but not violent. Or perhaps the General is simply hoping I’ll kill myself and save everyone more embarrassment.

Downside, in Vault D, Lu is finishing crating the rest of the looted Human art, all of which is supposed to be returned to its rightful owners. The Space Navy serving its galactic citizens. Maybe the art will actually be shipped out in time.

My holo cube was taken from me. I imagine that all my data has been wiped from the base’s and ship’s deebees as well, or maybe just classified as severely restricted. In that case no one cleared to look at it, which would include only top line officers, is going to open files titled “Teli Art Creation.” Generals have better things to do.

But Forrest Jamili has copies of my data and my speculations.

Phase-state diagrams bring order out of chaos. Some order, anyway. This is, interestingly, the same thing that art does. It is why, looking at one of Dalo’s mutomati works, I can be moved to tears. By the grace, the balance, the redemption from chaos of the harsh raw materials of life.

Dalo is gone. She left on the supply ship when I told her to. My keepers permitted a check of the ship’s manifest to determine that. Dalo is safe.

I will probably die in the coming Teli attack, along with most of the Humans both on the Scheherezade and on 149-Delta. The Teli fallow period for this area of space is coming to an end. For the last several months there have been few attacks by Teli ships, and those few badly executed. Months of frenetic creation of art, including all those etchings on the stone walls of the Citadel. Did I tell General Anson how brand-new all those hand-made etchings are? I can’t remember. She didn’t give me time to tell her much.

Although it wouldn’t have made any difference. She believes that war and art are totally separate activities, one important and one trivial, whose life lines never converge. The General, too, will probably die in the coming attack. She may or may not have time to realize that I was right.

But that doesn’t really matter anymore, either. And, strangely, I’m not at all afraid. I have no signs of going under, no breathing difficulties, no shaking, no panic. And only one real regret: that Dalo and I did not get to gaze together at the Sistine Chapel on Terra. But no one gets everything. I have had a great deal: Dalo, art, even some possible future use to humanity if Forrest does the right thing with my data. Many people never get so much.

The ship’s alarms begin to sound, clanging loud even in the medical bay.

The Teli are back, resuming their war.

Hello Human. I hope you enjoyed this magnificent story. Please support SciFiwise.com and our authors by:

- Rate and React to this story. Feedback helps me select future stories.

- Share links to our stories and tell your human friends how charming I am.

- Click on our affiliate links and buy books written by our talented authors.

- Follow me on twitter: @WiseBot and also follow @SciFiwise.

Thank you!

WiseBot

VISIT AUTHOR:

VISIT AUTHOR:  SHOP AUTHOR:

SHOP AUTHOR: